Resources

Glossary

Machine Bolt

Machine bolts are used to fasten wood to wood, wood to metal, and metal to metal. They are typically installed into pre-drilled and tapped holes and utilized in heavy-duty applications. Earnest Machine stocks Machine Bolts in grades 2, 5, and grade 8, providing options for applications requiring increased strength and durability. Earnest also offers Machine Bolts in various diameters, lengths, and finishes, including RoHS-compliant Zinc Clear Trivalent and hexavalent-free Zinc Yellow Trivalent.

Machine Screw Anchor

A machine screw anchor is a type of fastener used to secure machine screws into masonry or other solid materials like concrete, brick, or stone, where a regular screw wouldn’t hold. It’s essentially a sleeve or plug that gets inserted into a pre-drilled hole in the material. When a machine screw is threaded into the anchor, it expands or grips the surrounding material, creating a strong, reliable mounting point.

Machine Screws

Industrial machine screws are specialized fasteners used to secure components in machinery and equipment. They are designed for precise applications where reliable fastening is required, often involving the assembly of metal parts or the attachment of machine components. These screws come in a variety of sizes, materials, and head styles, making them versatile for different industrial needs.

Machining

A manufacturing process that removes material from a part to shape it into a specific design. In fastener production, machining is used to form precise dimensions, threads, or other features by cutting, drilling, turning, or milling the material with specialized equipment.

Magnesium (Mg)

Magnesium is a silvery-white metallic element with the chemical symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a lightweight, strong, and reactive metal that plays a crucial role in both industrial applications and biological systems. As the eighth most abundant element in Earth’s crust and a key component of seawater, magnesium is one of the most important metals for modern manufacturing and life processes alike.

In its pure metallic form, magnesium is one-third lighter than aluminum, making it one of the lightest structural metals. It combines low density, high strength-to-weight ratio, and excellent machinability, which makes it ideal for aerospace, automotive, and electronics industries. Magnesium alloys are often used to produce aircraft parts, transmission housings, laptop casings, and lightweight tools, helping reduce overall weight while maintaining durability.

Chemically, magnesium is highly reactive, especially in finely divided form. It readily reacts with oxygen to form magnesium oxide (MgO), a white powder that emits a bright white flame when the metal burns—this characteristic has made magnesium famous in fireworks, flares, and photographic flashes. When exposed to air, it forms a thin protective oxide layer that prevents rapid corrosion.

Magnesium is also an essential biological element—it is the fourth most abundant mineral in the human body and is necessary for over 300 enzymatic reactions, including energy production, muscle contraction, nerve function, and protein synthesis. It forms the central atom in chlorophyll, the green pigment that allows plants to capture sunlight during photosynthesis.

Common industrial magnesium compounds include magnesium oxide (MgO) used in refractories and insulation, magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)₂) used as a flame retardant and antacid, and magnesium sulfate (Epsom salt) used in medicine and agriculture.

Magnesium is typically extracted from magnesite (MgCO₃), dolomite (CaMg(CO₃)₂), and sea water, where it is separated through electrolysis or thermal reduction processes.

Magnesium Oxide (MgO)

Magnesium oxide (MgO) is a white, crystalline, inorganic compound formed by combining magnesium (Mg) and oxygen (O₂). It is a highly stable, non-flammable, and refractory material, meaning it can withstand extremely high temperatures without breaking down. Magnesium oxide occurs naturally as the mineral periclase, but it is most commonly produced synthetically by heating magnesium carbonate (MgCO₃) or magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)₂) until they decompose, releasing carbon dioxide or water.

When heated, magnesium reacts with oxygen to form magnesium oxide: 2 Mg + O₂ → 2 MgO

This exothermic reaction produces an intense white flame — a signature of magnesium combustion. The resulting MgO is a fine white powder or solid with a high melting point (~2,852°C or 5,166°F), making it useful in industrial furnaces, crucibles, kilns, and refractory bricks that line high-temperature equipment.

Magnesium oxide has a wide range of uses:

- In metallurgy, it serves as a refractory material and flux, protecting metals from oxidation.

- In construction, MgO boards are used as fire-resistant and mold-resistant alternatives to drywall or cement board.

- In environmental applications, it’s used to neutralize acidic wastewater and flue gases.

- In electrical and thermal insulation, MgO is used inside heating elements (such as in toasters and ovens) due to its high dielectric strength and ability to conduct heat while insulating electrically.

Magnesium oxide also reacts slowly with water to form magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)₂), a process known as hydration: MgO + H₂O → Mg(OH)₂

Magnetic Particle Testing (MT)

Magnetic Particle Testing (MT) is a non-destructive testing (NDT) technique designed to detect surface and near-surface defects in ferromagnetic materials like iron, nickel, cobalt, and their alloys. The process begins by magnetizing the part either through direct current or by placing it in a magnetic field. When the material contains a discontinuity—such as a crack, seam, lap, or void—it interrupts the flow of the magnetic field. This disruption causes magnetic flux leakage at the defect site, which provides the basis for detection. Finely milled ferromagnetic particles, applied as either a dry powder or a suspension in liquid, are then spread across the surface. These particles are drawn toward the leakage fields and cluster along the defect, forming a visible indication of its presence.

This method is widely applied across industries like aerospace, automotive, construction, and energy, especially for inspecting welds, castings, and forgings. MT offers several advantages: it is highly effective for finding surface-breaking flaws and shallow subsurface defects, produces immediate and easily visible results, and is relatively quick and inexpensive to perform. However, it does have limitations—it only works on ferromagnetic materials, requires clean surfaces for accurate detection, and may miss deeper flaws that methods like ultrasonic or radiographic testing could identify. Despite these constraints, MT remains a practical, versatile, and widely used inspection tool for ensuring the integrity of critical components.

Magnetite

Magnetite is a naturally occurring iron oxide mineral with the chemical formula Fe₃O₄, and it is one of the most important and magnetic iron ores in the world. It contains both ferrous (Fe²⁺) and ferric (Fe³⁺) iron ions, making it a mixed-valence oxide and giving it unique magnetic properties. In fact, magnetite is the most magnetic naturally occurring mineral on Earth, a property that distinguishes it from other iron ores such as hematite.

In appearance, magnetite is usually black or dark gray with a metallic luster and a high density. When streaked on a surface, it leaves a black streak, unlike hematite, which leaves a reddish-brown one. Its natural magnetism can be strong enough to attract small iron objects or align itself with Earth’s magnetic field, which is why it was historically known as lodestone and used in some of the earliest magnetic compasses.

Geologically, magnetite forms in a wide range of environments. It can crystallize directly from igneous magma, occur as a product of metamorphism, or form through chemical precipitation in sedimentary rocks. It’s commonly found in banded iron formations (BIFs)—ancient layered sedimentary deposits that supplied much of the world’s iron ore. Large magnetite deposits are found in Australia, Brazil, Sweden, Russia, the United States, and South Africa, often mined alongside hematite.

From an industrial standpoint, magnetite is a major source of iron for steelmaking. The ore is typically concentrated using magnetic separation, since its magnetic properties allow it to be easily distinguished and isolated from surrounding rock. After concentration, it is smelted in a blast furnace, where carbon reduces the Fe₃O₄ to metallic iron. The reaction is: Fe₃O₄ + 4CO → 3Fe + 4CO₂

Magnetite is also used in other applications beyond steel production. Finely ground magnetite serves as a dense medium in coal washing, where it helps separate coal from impurities by density. It’s used in catalysts, recording tapes, pigments, water purification, and even in medical applications such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents and targeted drug delivery systems.

Magni®

A family of engineered coating systems developed by Magni Industries, designed to protect fasteners and metal components against corrosion. Magni® coatings often combine an inorganic zinc-flake basecoat with an organic topcoat, offering customizable friction properties, color options, and high salt-spray resistance for automotive, construction, and heavy-equipment applications.

Major Diameter

The major diameter of a thread is the largest diameter of a screw thread, measured from the crest of the threads on one side to the crest on the opposite side. If you picture the threaded portion of a bolt or screw as a cylinder with ridges cut into it, the major diameter is the diameter of the imaginary cylinder that touches the very tops of those ridges.

For an external thread (such as a bolt), the major diameter is the diameter across the outermost points of the external threads. For an internal thread (such as a nut), it is the diameter measured across the innermost points of the internal thread crests. Because it represents the overall size of the thread, the major diameter is typically the dimension used when identifying or naming a threaded fastener. For example, in an M10 × 1.5 metric bolt, “10 mm” refers to the major diameter.

The major diameter is important because it sets the nominal size of the fastener and influences whether two threaded parts will fit together properly. While the major diameter itself doesn’t carry most of the load—that happens along the flanks at the pitch diameter—it ensures clearance, proper engagement, and compatibility between mating threads.

Together with the minor diameter (measured at the roots of the threads) and the pitch diameter (the effective diameter where threads engage), the major diameter is one of the three critical dimensions that define the geometry and function of a thread.

Manganese (Mn)

Manganese is a hard, brittle, silvery-gray metal with the chemical symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a transition metal that plays a crucial role in metallurgy, manufacturing, and biology. While not magnetic in its pure form, it is essential in steelmaking and alloy production due to its strength-enhancing and deoxidizing properties.

In industry, manganese is most widely used as an alloying element in steel—in fact, around 90% of all manganese produced goes into steel manufacturing. When added to iron, manganese improves tensile strength, hardness, and resistance to wear and impact, while also removing oxygen and sulfur impurities during smelting. Manganese steel (also known as Hadfield steel) is famous for its exceptional toughness and wear resistance, making it ideal for railway tracks, rock crushers, armor plating, and heavy machinery.

Manganese is also used in aluminum alloys to increase corrosion resistance and strength, and in batteries, especially alkaline and lithium-ion types, where it appears as manganese dioxide (MnO₂) in the cathode.

Chemically, manganese forms a wide range of oxides and compounds, with oxidation states from +2 to +7, giving rise to colorful salts used in glassmaking, pigments, and fertilizers. For example, potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) is a deep purple compound used as a powerful oxidizing agent in water treatment and chemical laboratories.

Biologically, manganese is an essential trace element required for enzyme function in both humans and plants. It supports bone formation, metabolism, and antioxidant activity, though excessive exposure to manganese dust or fumes (as in mining or welding) can cause neurological disorders known as manganism, similar to Parkinson’s disease.

Manganese occurs naturally in minerals such as pyrolusite (MnO₂) and rhodochrosite (MnCO₃), and major producers include South Africa, Australia, China, and Gabon.

AKA: Hadfield Steel

Martensite

Martensite is a hard, brittle microstructural phase formed in steel when austenite (the high-temperature FCC phase of iron) is rapidly cooled—or quenched—so quickly that carbon atoms don’t have time to diffuse. Because the transformation happens under diffusionless, high-speed conditions, the crystal structure shifts from face-centered cubic (FCC) to a highly strained body-centered tetragonal (BCT) form rather than transforming into ferrite + cementite (as it would during slow cooling).

This trapped carbon in a distorted lattice creates extremely high internal stress, which gives martensite its defining properties: very high hardness and strength, but low ductility and toughness. That’s why quenched steels are strong but brittle unless further treated.

After martensite forms, steels are typically tempered—heated to a much lower temperature (like 200–600°C)—to relieve stress, reduce brittleness, and allow controlled precipitation of carbides, producing tempered martensite, which offers a better balance of strength and ductility.

Martensite is the foundation of heat-treatable steels used for tools, springs, cutting edges, automotive components, gears, and high-strength fasteners. It is a cornerstone phase in metallurgy because controlling how much martensite forms—and how it is tempered—allows engineers to tune steel performance for extreme mechanical demands.

Martensitic Stainless Steel

Martensitic stainless steel is a category of stainless steel known for its high strength, hardness, and moderate corrosion resistance, achieved through heat treatment that transforms its crystal structure into martensite. It is characterized by a body-centered tetragonal (BCT) crystal structure, which forms when steel containing sufficient carbon is rapidly cooled or quenched from a high temperature. This gives martensitic stainless steels their distinctive ability to be hardened and tempered, much like carbon steels.

The composition of martensitic stainless steels typically includes 11.5% to 18% chromium and 0.1% to 1.2% carbon, with small amounts of other elements such as molybdenum, nickel, or vanadium to improve strength, corrosion resistance, and toughness. The chromium content provides the protective oxide layer that resists rust and oxidation, while the carbon allows for the formation of martensite during quenching, leading to significant hardness and wear resistance.

Unlike austenitic or ferritic stainless steels, martensitic grades are magnetic and can be heat treated to a wide range of hardness levels. However, this comes at a tradeoff: their corrosion resistance is generally lower, especially in environments involving chlorides or acids. They also tend to have reduced ductility and weldability compared to other stainless steel families.

Common martensitic grades include Type 410 (general-purpose, used for cutlery, valves, and turbine blades), Type 420 (high-carbon, used for surgical instruments and knives), and Type 440C (very high carbon, used for bearings, precision tools, and high-wear components). These steels are often used where mechanical strength, edge retention, and wear resistance are more critical than corrosion resistance.

Material Hardness

A material property describing resistance to surface deformation such as scratching, denting, or indentation. It is the underlying property that standardized tests quantify, while the resulting measurement or acceptable range is the hardness level.

Meissner Effect

The Meissner Effect is the defining feature of superconductivity, describing the phenomenon in which a material completely expels magnetic fields from its interior when it transitions into the superconducting state—that is, when it’s cooled below its critical temperature (Tc).

In ordinary conductive materials (metals like copper or aluminum), magnetic field lines can penetrate the material normally, and cooling them simply reduces electrical resistance without affecting the magnetic field. But in a superconductor, something far more dramatic happens. As the material cools below Tc, it not only loses all electrical resistance—it also actively repels magnetic fields from its interior. This occurs because the superconductor forms surface currents that generate magnetic fields exactly opposing the external field, causing the total internal magnetic field to drop to zero.

This phenomenon was discovered in 1933 by Walther Meissner and Robert Ochsenfeld, who found that magnetic flux lines were expelled from a sample of superconducting tin when it was cooled below its critical temperature in an existing magnetic field. Their observation proved that superconductivity is not merely perfect conductivity (which would allow magnetic fields to remain frozen inside) but rather a distinct thermodynamic phase with unique quantum mechanical properties.

The Meissner Effect is often illustrated through magnetic levitation. When a small magnet is placed above a superconducting material cooled below Tc, the magnetic field lines cannot penetrate the superconductor, and the resulting repulsion creates a stable lifting force that makes the magnet float or levitate. This visible effect is a direct consequence of the perfect diamagnetism of superconductors—that is, their ability to completely cancel internal magnetic fields.

Mathematically, the Meissner Effect is described by London’s equations, which show that magnetic fields decay exponentially from the surface of a superconductor over a characteristic distance called the London penetration depth (λ), typically just a few hundred nanometers. Inside the material beyond this depth, the magnetic field is effectively zero.

Mercury (Hg)

Mercury (chemical symbol Hg) is a heavy, silvery-white metallic element that is unique among metals because it remains liquid at room temperature. It has an atomic number of 80, an atomic mass of 200.59, and belongs to Group 12 of the periodic table, along with zinc (Zn) and cadmium (Cd). The name “Hg” comes from its Latin name hydrargyrum, meaning “liquid silver.”

Mercury is dense, lustrous, and highly mobile, with a melting point of −38.83°C (−37.89°F) and a boiling point of 356.7°C (674°F). It is a poor conductor of heat compared to most metals but an excellent conductor of electricity, which historically made it useful in electrical switches, relays, and thermometers. Because of its ability to form amalgams—alloys with many metals such as gold, silver, and tin—mercury was once widely used in mining, dentistry, and manufacturing.

In the past, mercury had many industrial and scientific applications. It was used in thermometers, barometers, fluorescent lamps, and electrical components, and its vapor was key in early mercury-arc rectifiers and vacuum tubes. However, mercury and most of its compounds are now known to be highly toxic, capable of causing severe neurological and organ damage even at low levels of exposure. For this reason, most of its traditional uses have been phased out or tightly controlled.

Mercury naturally occurs in the Earth’s crust, primarily as the mineral cinnabar (mercury sulfide, HgS), which has a deep red color. It is extracted by heating cinnabar ore in air, which causes the sulfur to combine with oxygen and release elemental mercury vapor, later condensed into liquid form. Small amounts of mercury are also released naturally from volcanic activity and weathering of rocks.

Chemically, mercury is relatively unreactive. It does not oxidize readily in air at room temperature but forms compounds like mercuric oxide (HgO) and mercuric chloride (HgCl₂) under heat or chemical reaction. Mercury can exist in two common ionic states: Hg⁺¹ (mercurous) and Hg⁺² (mercuric), leading to a variety of inorganic and organic compounds—many of which are environmentally persistent and biologically harmful, such as methylmercury (CH₃Hg⁺).

Today, mercury use is heavily restricted due to its toxicity and environmental persistence. Modern technology has largely replaced it with safer alternatives in thermometers, electrical switches, and batteries. However, it still finds limited use in specialized applications such as scientific instruments, dental amalgams, and fluorescent lighting—though even these are declining.

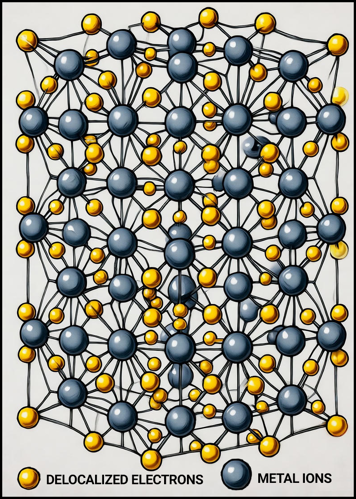

Metallic Bonding

Metallic bonding is the type of chemical bonding that occurs between metal atoms, characterized by a structure in which positively charged metal ions are surrounded by a “sea” of delocalized electrons. Unlike ionic or covalent bonds—where electrons are either transferred or shared between specific atoms—metallic bonding involves electrons that move freely throughout the metal lattice.

These free electrons act like glue, holding the metal cations together through electrostatic attraction. Because the electrons are not bound to any particular atom, they can move easily through the structure, which gives metals their unique physical properties—such as electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, malleability, and ductility.

When a force is applied to a metal, the layers of atoms can slide over each other without breaking the bond because the electron “sea” continuously readjusts to maintain attraction between the ions. This is why metals can be shaped and stretched without fracturing.

Metalloid

A metalloid is a type of element that exhibits properties intermediate between those of metals and nonmetals. Metalloids have a unique combination of characteristics—some metallic, such as luster, electrical conductivity, and the ability to form alloys, and some nonmetallic, such as brittleness and poor heat conduction. This hybrid nature makes them extremely important in semiconductor technology, alloys, and chemical applications.

On the periodic table, metalloids typically appear along the diagonal “stair-step” line that separates metals (on the left) from nonmetals (on the right). The most commonly recognized metalloids are boron (B), silicon (Si), germanium (Ge), arsenic (As), antimony (Sb), and tellurium (Te). Some classifications also include polonium (Po) and astatine (At) depending on their behavior in chemical reactions.

Metalloids often have metallic appearance and moderate electrical conductivity, which can be adjusted by temperature, impurities, or doping—a property that makes them ideal for semiconductors. For example, silicon and germanium are the backbone of the electronics industry, used in computer chips, transistors, and solar cells. Arsenic and antimony, meanwhile, are used to modify alloys, harden lead, or enhance flame retardancy.

Chemically, metalloids can form compounds with both metals and nonmetals, and their oxides often show amphoteric behavior—meaning they can act as either acids or bases. This dual nature reflects their position between the two extremes on the periodic table.

Metallurgy

Metallurgy is the branch of science and engineering that studies the properties, behavior, and processing of metals and their alloys. It involves understanding how the structure of metals—from the atomic level to the macroscopic scale—affects their performance, strength, and durability under different conditions.

The field of metallurgy can be divided into three main areas. Physical metallurgy focuses on how the internal structure of metals (such as grain size, crystal structure, and dislocations) influences their mechanical, electrical, and magnetic properties. Extractive metallurgy deals with the processes used to obtain metals from their ores, including smelting, refining, and electrolysis. Mechanical or industrial metallurgy applies this knowledge to the design, manufacturing, and treatment of metal products—covering processes like casting, forging, heat treatment, and welding.

Metallurgy plays a crucial role in nearly every industry that uses metals, including automotive, aerospace, construction, energy, and manufacturing. By understanding and controlling metallurgical processes, engineers can enhance metal performance, prevent failures such as corrosion or fatigue, and develop new materials with tailored properties for specific applications.

Metric

A system of measurement based on meters, centimeters, and grams, used internationally. In fasteners, “metric” refers to sizes and dimensions measured in millimeters.

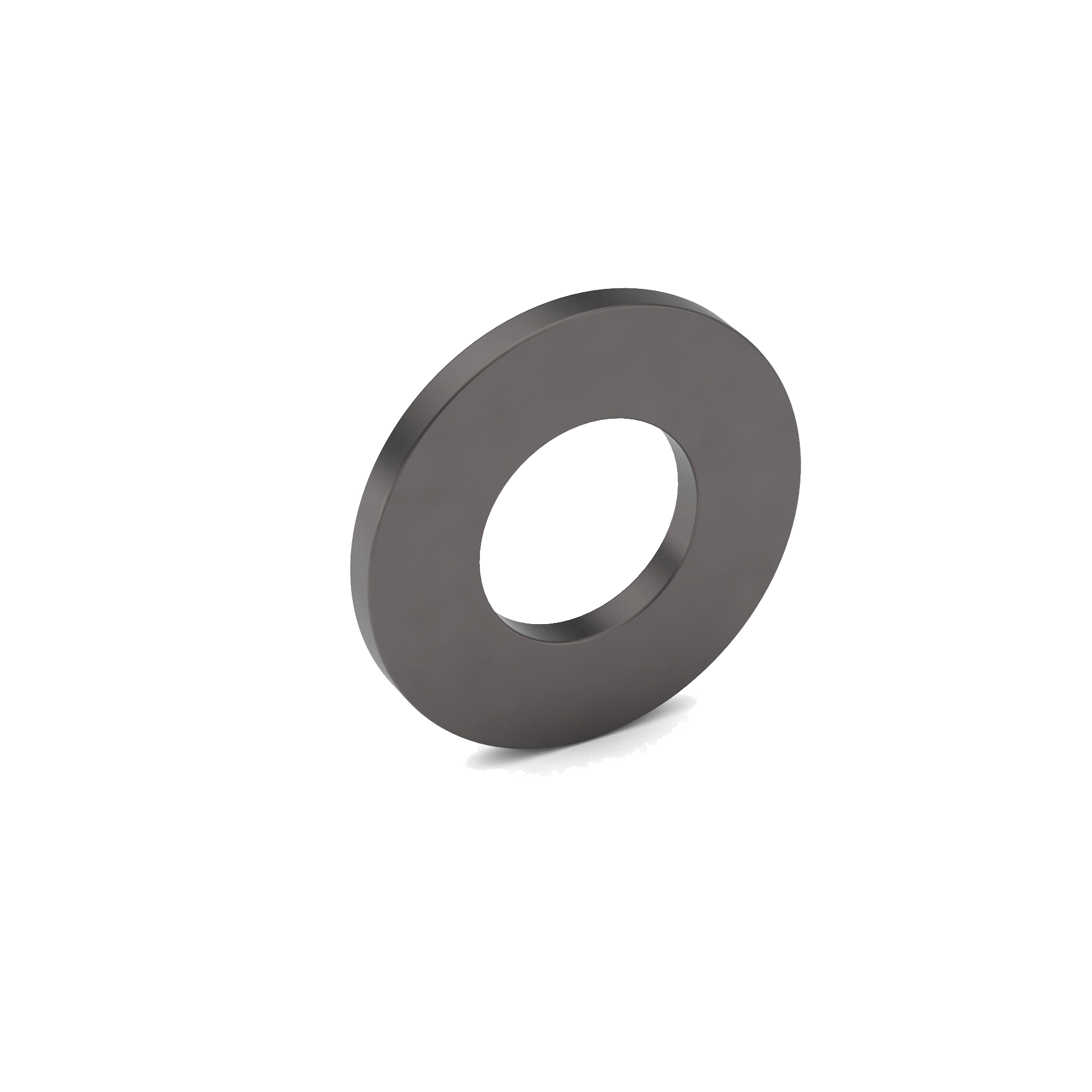

Metric Flat Washer

A metric flat washer is a thin, round, flat piece of metal or plastic with a central hole that corresponds to a metric-sized fastener, such as a bolt or screw. It is used to distribute the load of the fastener more evenly across the surface of the material being fastened, preventing damage, reducing friction, and ensuring a more secure connection.

Metric Hardened Flat Washer

A metric hardened flat washer is a type of flat washer designed according to metric dimensions (millimeters) and made from hardened steel. The hardening process involves heat treatment to increase the washer's strength and durability, making it suitable for high-stress applications. These washers are used to distribute the load of a fastener, such as a bolt or screw, over a larger surface area, protect the material being fastened, and reduce wear.

Metric Heavy Hex Nut

A metric heavy hex nut is a type of fastener designed with a hexagonal (six-sided) shape, similar to standard hex nuts, but with a thicker and larger profile. These nuts are commonly used in applications where additional strength and durability are required, particularly in high-load or high-stress environments.

Metric Hex Head Cap Screw

A metric hex head cap screw is a type of fastener that has a hexagonal (six-sided) head and a threaded shaft, designed to be used with metric-sized nuts or tapped (threaded) holes. The hex head allows for easy tightening and loosening using a wrench or socket. These screws are commonly used in machinery, automotive, construction, and structural applications, where precise, strong, and reliable fastening is required.

Metric Hex Head Cap Screw (ANSI)

A Metric Hex Head Cap Screw (ANSI) is a type of threaded fastener with a hexagonal (six-sided) head, used for securing materials or components. It is manufactured to metric dimensions and follows specifications set by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). These screws are widely used in machinery, construction, automotive, and many other applications.

Metric Hex Jam Nut

Hex Jam Nuts are half the thickness of standard Hex Nuts and are commonly used in applications where a nut with a low-profile thickness is needed. This nut can also be used with a standard Hex Nut to create a locking action in your assembly. Earnest Machine stocks the largest selection of Hex Jam Nuts in industry, offering both inch and metric sizes with a variety of strength levels, thread directions, and finishes to choose from.

Metric Hex Wheel Nut

Otherwise known as Lug Nuts, Wheel Nuts are specifically designed to hold tire rims to an axle. These nuts are primarily used in automotive and construction equipment. In order to match the rim, the nuts are engineered to 60 degree, 90 degree, and radius faces.

Metric Nylon Insert Hex Flange Lock Nut

A metric nylon insert hex flange lock nut is a specialized fastener that combines several important features: a hexagonal shape, a built-in flange, and a nylon insert to provide a secure, vibration-resistant fastening solution. This type of nut is commonly used in applications where both high torque and resistance to loosening are important.

Metric O-Rings

A metric nylon insert hex flange lock nut is a specialized fastener that combines several important features: a hexagonal shape, a built-in flange, and a nylon insert to provide a secure, vibration-resistant fastening solution. This type of nut is commonly used in applications where both high torque and resistance to loosening are important.

Microscrew

A microscrew (miniature screw) is a very small machine screw used to fasten tiny components where space and weight are limited—think electronics, wearables, cameras, watches, and medical devices. In practice, people usually mean sizes ≤ M2 in metric (e.g., M1.6, M1.4, M1.2, M1.0, M0.8) or #0-80 and smaller in inch series (down to #0000-160). They’re made in common head styles (pan, flat, button, socket), drives (Phillips/JIS, Torx®, slotted), and materials like stainless steel, titanium, and brass, with finishes such as passivation or black oxide.

Because everything is tiny, installation uses low, precise torque (often measured in cN·m/N·cm), fine thread classes, and magnified/ESD-safe handling. Variants include thread-forming microscrews for plastics and micro set screws for collars/gears. The key idea: a standard screw in every way—just engineered for microscale assemblies with tight tolerances.

Microstructural Inhomogeneities

Microstructural inhomogeneities are small-scale irregularities or non-uniformities within the internal structure of a material, usually visible under a microscope. Instead of having a perfectly even composition and arrangement of grains, phases, or inclusions, the material contains localized variations that make certain regions behave differently under stress, temperature, or chemical exposure.

These inhomogeneities can take many forms. Common examples include non-metallic inclusions (like oxides or sulfides in steel), segregations of alloying elements during solidification, uneven grain sizes, voids, porosity, or differences in phase distribution (such as harder or softer regions in a heat-treated alloy). They may also include dislocations, twins, or other crystal defects.

While some microstructural variation is normal in engineered materials, significant inhomogeneities often act as weak points. They can disrupt the even flow of stress through the material, leading to stress concentrations that make crack initiation more likely. In fatigue, corrosion, and fracture mechanics, microstructural inhomogeneities are often the hidden initiators behind failure.

Controlling these features is a key part of materials engineering. Careful processing, refining, alloying, and heat treatment are all used to minimize unwanted inhomogeneities and produce consistent, predictable material performance. In advanced applications like aerospace, medical implants, or nuclear power, even tiny microstructural irregularities can be critical to long-term reliability.

Mil-Spec (Military Specification)

A standard or specification developed by the U.S. Department of Defense that defines the performance, quality, and testing requirements of a product. Fasteners labeled “Mil-Spec” must meet strict requirements for material, strength, corrosion resistance, and uniformity, ensuring reliability in defense and aerospace applications.

Milling Cutter

A milling cutter is a rotating, multi-edge cutting tool used on milling machines and CNCs to remove material by shearing chips. Unlike a single-point lathe tool or a drill’s two lips, a milling cutter has many teeth that intermittently engage the work, so metal removal comes from the combined action of multiple edges as the tool feeds along a path.

Key anatomy features include the shank or arbor hole, which determines how the tool mounts—either a solid-shank cutter or a shell/face mill mounted on an arbor. The body carries flutes and teeth; the flutes form chip channels, while tooth geometry establishes rake, relief, and helix angle to control chip flow and cutting forces. Cutting diameter and length of cut set the practical step-over and depth capability. Edge style can be square, corner-radius, or ball nose; center-cutting end mills can plunge, whereas non-center-cutting designs cannot.

Common cutter types span end mills (square, ball, corner-radius) for profiling and pocketing, typically with 2–3 flutes for aluminum and 4–6 for steels; face mills or shell mills for planar surfacing using indexable inserts; and slab/plain, side-and-face, T-slot, Woodruff/keyseat, dovetail, and other form cutters that produce specific profiles. Additional families include chamfer and deburr mills, counterbores and countersinks, and thread mills that generate internal or external threads with CNC helical paths.

Cutter materials and coatings are chosen for the job. HSS and cobalt HSS are tough and forgiving but run at lower speeds. Solid carbide is stiff and wear-resistant for high-speed CNC work. Indexable platforms use carbide, ceramic, CBN, or PCD for larger diameters and hard or abrasive materials. Coatings—applied via PVD or CVD—such as TiN, TiCN, TiAlN/AlTiN, and DLC reduce wear and built-up edge; selection should match the work material and expected heat.

Choosing a cutter follows a straightforward logic. By material: aluminum favors high-helix 2–3-flute tools; steels run well with 4–6-flute AlTiN-coated carbide; stainless benefits from a tough grade, sharp edge, and lower helix; titanium and nickel alloys call for variable-pitch carbide and high rigidity. By operation and toolpath: facing suggests a face mill; deep pocketing and 3D work point to a ball or variable-helix end mill; keyways use keyseat cutters; threads benefit from thread milling for better control than tapping. Machine and toolholding matter—stiffer holders (heat-shrink, ER, whistle-notch) and minimal overhang reduce chatter. Chip control depends on flute count and helix for evacuation, and on whether to use coolant, MQL, or run dry, based on the material.

Practical use tips round it out. Prefer climb milling on CNC for better finish and tool life, reserving conventional milling for specific setups. Set feed per tooth (fz) and surface speed (Vc) from manufacturer data, and tune radial (ae) and axial (ap) engagement to avoid chatter. Monitor wear modes: built-up edge suggests raising speed or adding a suitable coating; chipping points to reducing runout or lightening radial engagement; and thermal cracking calls for avoiding intermittent coolant and reducing coolant cycling.

Minor Diameter

The minor diameter of a thread is the smallest diameter of a screw thread, measured from the root of the threads on one side to the root on the opposite side. If you imagine the thread profile as peaks (crests) and valleys (roots), the minor diameter corresponds to the imaginary cylinder that just touches the bottoms of all the thread grooves.

For an external thread (like on a bolt), the minor diameter is the diameter at the base of the external threads. For an internal thread (like in a nut), it is the diameter measured across the crests of the internal threads. In both cases, the minor diameter represents the narrowest point of the threaded section.

The minor diameter is important because it directly affects the strength of the fastener. Since this dimension determines the thickness of the metal left at the root of the thread, it defines how much shear area is available to resist stripping. A larger minor diameter means more material in the cross-section and generally higher strength, while a smaller one means the fastener may be weaker.

Along with the major diameter (measured across the crests of the threads) and the pitch diameter (the effective diameter where the threads of a nut and bolt actually contact each other), the minor diameter is one of the three key dimensions that define a thread’s geometry and ensure proper fit and load distribution.

Mohs Hardness Scale

The Mohs Hardness Scale is a comparative scale that measures the relative hardness of minerals and other materials based on their ability to resist scratching. It was developed in 1812 by German mineralogist Friedrich Mohs and is still widely used today as a quick, practical way to rank material hardness. The scale ranges from 1 to 10, with 1 being the softest and 10 the hardest. Each mineral on the scale can scratch any material ranked lower than itself, but not those higher.

At the soft end, talc is ranked at 1, meaning it can be easily scratched by any other mineral. At the hardest end, diamond is ranked at 10, representing the maximum hardness in natural materials. Other familiar examples include gypsum (2), calcite (3), fluorite (4), apatite (5), feldspar (6), quartz (7), topaz (8), and corundum (9, which includes sapphires and rubies).

The Mohs Scale is not linear but ordinal, meaning the difference in hardness between successive numbers is not equal. For example, diamond (10) is much harder compared to corundum (9) than corundum is compared to topaz (8). Despite this, the scale is practical for fieldwork and industry because it gives a fast and simple way to test hardness using scratch comparisons.

In the context of fasteners and industrial applications, the Mohs Hardness Scale is relevant for understanding wear resistance, abrasion resistance, and material compatibility. For example, coatings, cutting tools, and surface treatments are often selected based on hardness relative to the materials they will interact with. While engineers often use more precise hardness measures such as Rockwell, Vickers, or Brinell hardness tests, the Mohs scale remains a useful reference for comparing material durability in general terms.

Molybdenum (Mo)

Molybdenum (chemical symbol Mo, atomic number 42) is a strong, silvery-gray metallic element valued for its ability to greatly improve the strength, hardness, and high-temperature performance of steel and other metal alloys. It is often used in small percentages (typically 0.1–1%) but has a major impact on how metals behave under stress, heat, and corrosive environments.

In the context of metallurgy and fasteners, molybdenum plays several crucial roles:

High-Temperature Strength:

Molybdenum has one of the highest melting points of all elements (4,752°F / 2,620°C). When added to steel, it helps the alloy maintain its strength and stiffness even at elevated temperatures. This makes it ideal for automotive, aerospace, and industrial fasteners that must perform under heat and load.

Improved Toughness and Ductility:

It increases the toughness of steel—its ability to deform slightly before breaking—without making it brittle. This means molybdenum-alloyed steels resist cracking or fracturing under shock or cyclic stresses.

Enhanced Corrosion Resistance:

Molybdenum improves resistance to pitting, crevice corrosion, and chemical attack, particularly in chloride or acidic environments. This is why stainless steels containing molybdenum (like 316 stainless) perform well in marine and chemical settings.

Strengthening and Hardening Agent:

It helps form carbides (molybdenum carbides) within steel, which significantly increase wear resistance and surface hardness.

Synergy with Chromium:

When combined with chromium (as in chromoly steel), molybdenum refines the steel’s grain structure, making it stronger, tougher, and more stable under high stress and temperature.

Because of these properties, molybdenum is used in fasteners, turbine blades, furnace parts, engine components, and high-strength tools. In fastener manufacturing, molybdenum-alloyed steels (like 4140 or 8740 chromoly) are common in bolts, studs, and nuts where both strength and reliability under heat are essential.

Monel

Monel is a nickel–copper alloy known for its exceptional resistance to corrosion, high strength, and durability in harsh chemical and marine environments. It typically contains about 65–70% nickel, 20–30% copper, and small amounts of iron, manganese, carbon, and silicon. The combination of nickel and copper produces a material that is stronger than pure nickel, yet retains excellent resistance to acids, alkalis, seawater, and atmospheric corrosion.

Composition and Types

The general formula for Monel alloys includes:

- Nickel (Ni): 63–70%

- Copper (Cu): 20–29%

- Iron (Fe): 1–2.5%

- Manganese (Mn): up to 2%

- Silicon (Si) and Carbon (C): trace amounts

There are several grades of Monel, each tailored for specific uses:

- Monel 400: The most common grade; offers excellent resistance to seawater, hydrofluoric acid, and alkalis, with good mechanical properties from subzero to about 480°C (900°F).

- Monel K-500: A precipitation-hardened version that adds aluminum and titanium for higher strength and hardness while retaining corrosion resistance.

Properties

Monel exhibits several outstanding properties that make it ideal for extreme conditions:

- Corrosion Resistance: Excellent resistance to saltwater, steam, hydrofluoric acid, sulfuric acid, and alkaline environments.

- Mechanical Strength: High strength and toughness, even at low or cryogenic temperatures.

- Nonmagnetic: Monel 400 remains essentially nonmagnetic, which is useful in precision and naval equipment.

- Workability: Can be hot- or cold-worked, machined, and welded, though it’s tougher to machine than standard steels due to its high strength.

Applications

Because of its durability and corrosion resistance, Monel is used extensively in marine, chemical, and aerospace industries:

- Marine engineering: Propeller shafts, seawater valves, pump shafts, and heat exchangers.

- Chemical processing: Equipment for handling hydrofluoric and sulfuric acids, alkali production, and chlorinated solvents.

- Aerospace and defense: Fuel tanks, exhaust systems, and fasteners.

- Oil and gas industry: Cladding for piping, pumps, and downhole equipment exposed to sour gas and brine.

- Musical instruments: Used in trumpet pistons, French horn rotors, and guitar strings for its corrosion resistance and smooth action.

Morgan Impact Bend Angle Nail Test

The Morgan Impact Bend Angle Nail Test is a specialized mechanical test used to evaluate the toughness, ductility, and bend resistance of nails. It is designed to determine how well a nail can withstand impact and bending forces without cracking, breaking, or failing prematurely.

In the test, a nail is driven against or bent over a specified angle using a controlled impact load, often with a pendulum or hammer-like device. The nail is struck until it bends to a predetermined angle, and the degree of bending and the condition of the nail afterward (whether it bends smoothly, fractures, or shows signs of brittleness) are recorded.

The purpose of the Morgan test is to replicate the kinds of stresses a nail might face during real-world use — for example, when being hammered into tough materials or subjected to repeated impact in structural applications. A nail that passes the test demonstrates good impact resistance, bending capacity, and toughness, qualities important in construction, woodworking, and heavy-duty fastening.

This test is often cited in quality control and standardization for nail manufacturing, as it helps ensure that nails meet performance requirements for durability and safety.