Resources

Glossary

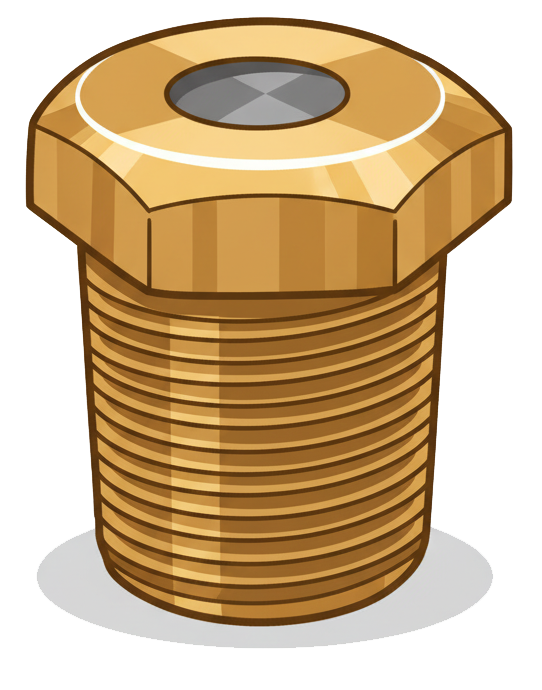

F436 Hardened Round Structural Washer

A Hardened Round Structural Washer is a specialized type of washer used in heavy-duty structural applications, designed to provide additional strength and load distribution in high-stress environments. These washers are hardened through heat treatment to increase their durability and resistance to deformation under pressure. They are commonly used in conjunction with high-strength bolts in structural steel connections, such as those found in buildings, bridges, and other large infrastructure projects.

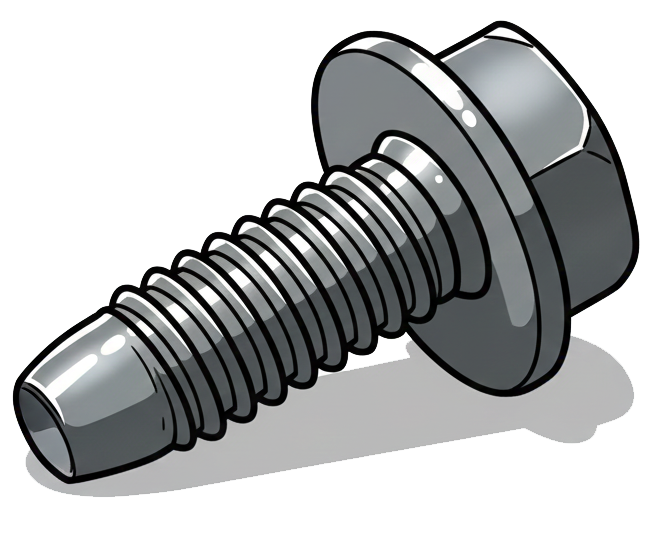

Farmer Screw

A farmer screw is a self-drilling fastener commonly used in agriculture and construction to attach metal roofing and siding panels to wood or steel frames. It typically features a hex washer head for strong torque, a bonded EPDM sealing washer to keep out water, and a sharp or self-drilling tip to pierce sheet metal without pre-drilling.

These screws are widely used on barns, sheds, silos, and other farm structures because they install quickly, resist weather, and securely hold panels against wind and vibration. Their combination of durability and ease of use makes them the go-to choice for fastening corrugated panels in outdoor environments.

Fastener Quality Act

A U.S. law enacted to ensure the quality and traceability of certain types of fasteners used in critical applications. The Fastener Quality Act requires that covered fasteners meet specified standards and are tested by accredited laboratories. It also mandates proper documentation and identification, such as lot numbers and manufacturer’s marks, to help prevent the use of substandard or mismarked fasteners in safety-critical environments like aerospace, automotive, and construction.

Fatigue

A progressive mode of failure in a fastener or its material caused by repeated or fluctuating (cyclic) stresses, even when those stresses are below the material's static strength limits. Over time, these dynamic loads lead to the initiation and growth of microscopic cracks, gradually weakening the fastener. This can result in sudden, unexpected fracture without significant prior deformation, making fatigue a critical concern for fasteners exposed to vibration or alternating loads.

Fatigue Strength

The maximum level of cyclic or fluctuating stress that a fastener can withstand for a specified number of cycles without experiencing fatigue failure. This property quantifies a fastener's resistance to the progressive damage caused by repeated loads. It is a critical design consideration for fasteners in applications subjected to vibration, repeated loading/unloading, or other dynamic conditions.

Fatigue-Crack Initiators

Fatigue-crack initiators are the small imperfections, features, or stress concentrations in a material where fatigue cracks are most likely to begin under repeated cyclic loading. They act as the “starting points” for cracks that can grow progressively with each load cycle until the material eventually fails.

These initiators can come from many different sources. On the surface, rough machining marks, scratches, dents, or corrosion pits can all create localized stress concentrations that trigger cracks. In the material itself, inclusions, voids, microstructural inhomogeneities, or welding defects can serve the same role. Even intentional design features, such as sharp corners, keyways, or threaded regions, are common fatigue-crack initiators because they naturally concentrate stress.

Once a fatigue crack initiator is present, cyclic stresses focus at that location. Even if the overall applied stress is below the material’s yield strength, repeated loading and unloading gradually weaken the area around the defect. Over time, microscopic cracks form at the initiator site, eventually propagating and leading to visible cracks and final fracture.

Controlling fatigue-crack initiators is a major goal in engineering and design. Processes like polishing, shot peening, surface coatings, and proper fillet radii are used to reduce stress concentrations. High-quality material selection, careful manufacturing, and preventive maintenance are equally critical in minimizing the sites where fatigue cracks can nucleate and threaten the reliability of a component.

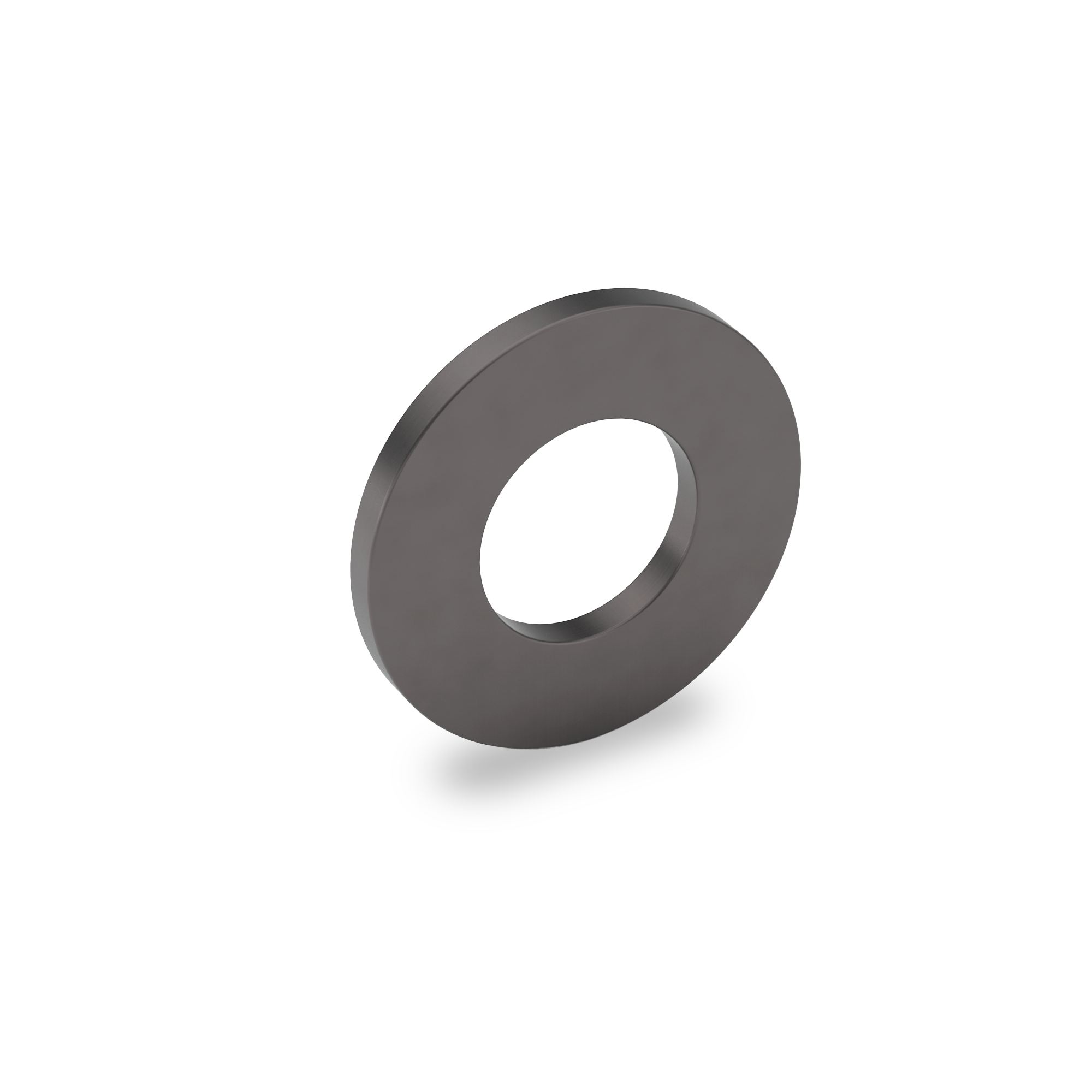

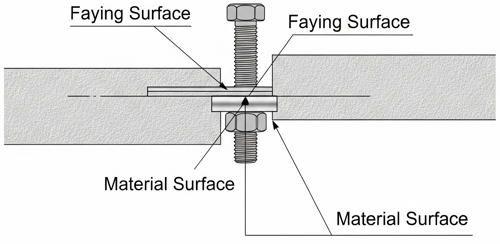

Faying Surface

A faying surface refers to the contacting surfaces between two components that are joined together in an assembly, usually by fasteners, welding, or adhesives. In fasteners specifically, the faying surface is the area of the parts that directly touch each other when clamped by bolts, rivets, or screws.

The condition of the faying surface is critical to joint performance. For example, in friction grip bolted joints, the clamping force of the bolt creates friction at the faying surface, which carries the load. If the surfaces are contaminated with paint, oil, rust, or coatings that reduce friction, the joint may slip or lose strength. Engineering standards often specify whether faying surfaces must be cleaned, roughened, or treated with certain coatings to ensure proper load transfer and durability.

Where you’ll see it

Structural steel connections in bridges, towers, and buildings.

Aerospace assemblies where precise load transfer is required.

Automotive and machinery joints relying on high-strength bolts or rivets.

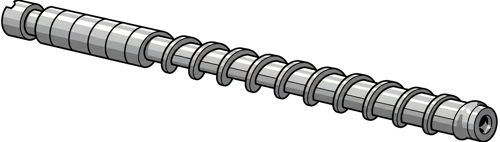

Feed Screw

A feed screw is a threaded mechanical component used to move material, parts, or machinery in a controlled, linear motion as it rotates. Instead of fastening like a normal screw, a feed screw functions as a motion-transfer device, converting rotary motion into precise linear displacement. They are essential in machines that need controlled feeding, positioning, or metering.

Where Feed Screws Are Used

Manufacturing & Automation

In CNC machines, lathes, and mills, feed screws (often ball screws or lead screws) move cutting tools or workpieces accurately along machine axes.

Packaging & Conveying

On production lines, a feed screw (also called a timing screw or metering screw) rotates to space, orient, or accelerate items like bottles, cans, or jars so they enter downstream equipment (fillers, cappers, labelers) in a synchronized flow.

Extrusion & Material Handling

In plastic and metal extrusion, a feed screw moves raw material forward while compressing and heating it.

Felt Washer

A felt washer is a flat, circular gasket made from compressed felt fibers, typically with a hole in the center like a standard washer. It’s used to seal, cushion, dampen vibration, absorb lubricants, and prevent leakage of fluids or dust between mechanical components.

Felt washers are made from natural wool, synthetic fibers, or a blend of both, which are densely compressed and heat-treated to achieve the desired thickness and density. Because felt is both porous and resilient, these washers combine flexibility, absorbency, and compression resistance—allowing them to conform tightly to irregular surfaces while maintaining a seal.

They are commonly used in automotive, plumbing, and machinery applications. In engines and gear systems, felt washers act as oil or grease retainers, slowly releasing lubricant to moving parts and keeping contaminants out. In plumbing and household fixtures, they function as soft seals to prevent water leaks while providing a cushion between metal parts. They’re also used in electrical equipment, fans, and small appliances to reduce noise and vibration by absorbing mechanical shocks and preventing metal-to-metal contact.

Depending on their density and intended use, felt washers can be soft and absorbent (for sealing or lubrication) or hard and dense (for spacing or damping). They are often compared to rubber or fiber washers but offer advantages in applications requiring both flexibility and absorbency, particularly where lubrication or dust control is important.

Fender Bolt

A fender bolt is a type of automotive fastener used to secure vehicle fenders, body panels, splash shields, and related trim pieces to the chassis or frame. These bolts typically feature a wide flange or integral washer under the head, which distributes load over a larger contact area to prevent damage to thin sheet metal panels—similar in principle to how fender washers are designed for wide load distribution.

Fender bolts are commonly found in areas like wheel wells, bumper-to-fender interfaces, underbody plastic liners, and mounting points where corrosion exposure, vibration, and thin-gauge metal are factors. They are often paired with U-nuts, clip nuts, or speed nuts, allowing installation into stamped sheet metal without requiring tapped holes. Because they’re used in exposed or semi-exposed locations, fender bolts often have corrosion-resistant finishes such as zinc plating, e-coating, black phosphate, stainless steel, or painted/automotive-matched coatings.

Their heads may be hex, flange hex, Torx, Phillips, or specialty OEM drive styles, depending on manufacturer and vehicle series. The bolt design focuses less on high structural strength and more on panel alignment, ease of assembly, corrosion resistance, and vibration resistance.

Fender Washers

A fender washer is a type of flat washer that has a much larger outer diameter compared to its inner (hole) diameter. It serves the same basic purpose as a regular washer—distributing the load of a fastener—but covers a much wider area, making it ideal for use with thin, soft, or brittle materials like sheet metal, plastic, fiberglass, or wood.

The large surface area of a fender washer spreads the clamping force over a broader section of the material, helping to prevent pull-through, warping, or damage. This makes it especially useful when fastening to slots, oversized holes, or irregular surfaces, where a standard washer would not provide enough coverage or stability.

Fender washers are often made from zinc-plated steel, stainless steel, brass, or nylon, and they come in a wide range of diameters. The name “fender washer” comes from their original use in automotive fender assemblies, where they helped distribute load and vibration around mounting holes in thin sheet metal.

Today, they’re used in automotive, marine, construction, HVAC, and general repair applications, as well as in DIY projects where reinforcement is needed around bolts or screws.

Ferritic Stainless Steel

Ferritic stainless steel is a type of stainless steel primarily composed of iron and chromium, with a body-centered cubic (BCC) crystal structure known as the ferritic phase. Unlike austenitic stainless steels, ferritic grades contain little to no nickel, which makes them more affordable but also less ductile. They are magnetic, have moderate corrosion resistance, and exhibit excellent resistance to stress corrosion cracking.

The chromium content in ferritic stainless steels typically ranges from 10.5% to 30%, which provides a protective oxide layer that resists oxidation and rust. However, since they lack significant amounts of nickel and other stabilizing elements, they are less resistant to highly corrosive or acidic environments compared to austenitic stainless steels. They also have lower toughness, especially at low temperatures, and are not hardenable by heat treatment, though they can be strengthened through cold working.

Ferritic stainless steels are known for their good thermal conductivity, resistance to scaling at high temperatures, and minimal thermal expansion, which makes them especially useful in automotive exhaust systems, heat exchangers, furnace components, and architectural trim. They are also favored in applications where magnetic properties are desirable or where cost reduction is important, since the absence of nickel significantly lowers material expense.

Common ferritic stainless steel grades include Type 409, used widely in automotive exhaust systems, Type 430, common in kitchen appliances and architectural panels, and Type 446, which offers excellent resistance to oxidation and scaling in high-temperature environments.

Ferrochrome

Ferrochrome (chemical symbol FeCr) is a metallic alloy of iron and chromium, produced by smelting chromite ore (FeCr₂O₄) with a carbon source such as coke or coal. It is the primary raw material used to make stainless steel, providing the chromium content that gives stainless steel its corrosion resistance, hardness, and brilliant finish.

Ferrochrome typically contains 50% to 70% chromium by weight, with the remainder being iron and small amounts of carbon, silicon, sulfur, and phosphorus. Depending on its carbon content, ferrochrome is classified into several grades. High-carbon ferrochrome (HC FeCr), which contains 4–8% carbon, is the most common type and is used in standard stainless steel production. Medium-carbon ferrochrome (MC FeCr) contains 1–4% carbon and is used when lower carbon levels are required in steel. Low-carbon ferrochrome (LC FeCr) contains less than 0.5% carbon and is used for specialty steels and superalloys that demand superior purity and performance.

The manufacturing process of ferrochrome begins with the mining and refining of chromite ore. The ore is then mixed with coke and fluxes and heated in a submerged-arc furnace at temperatures around 2,800°F to 3,000°F (1,540°C to 1,650°C). During the smelting process, carbon reduces chromium oxide to metallic chromium in the reaction FeCr₂O₄ + 4C → Fe + 2Cr + 4CO. This produces molten ferrochrome and carbon monoxide gas. Once the reduction is complete, the molten alloy is cast into ingots or granulated and crushed for industrial use, depending on the intended application.

Ferrochrome’s main application is in stainless steel production, where roughly 70–80% of all ferrochrome produced worldwide is consumed. A standard grade such as 304 stainless steel typically contains about 18% chromium, which comes entirely from ferrochrome. It is also used in alloy steels to increase hardness, wear resistance, and high-temperature strength, making it valuable in tool steels, ball bearings, and automotive components. In superalloys and specialty metals, ferrochrome contributes to the strength and oxidation resistance required in aerospace, power generation, and other high-stress industrial parts. Additionally, some ferrochrome is further processed into chromium metal or chromium oxide, which are used in plating, pigments, and chemical catalysts.

Ferrous Metal

A ferrous metal is any metal or alloy where iron is the primary constituent—most commonly carbon steel, alloy steel, and many stainless steels. These materials are often magnetic (though some stainless grades aren’t, depending on structure and heat treatment) and they’re the backbone of most structural and general-purpose fasteners.

Ferrovanadium Alloy

Ferrovanadium is an iron–vanadium alloy used primarily as a strengthening additive in steel production. It typically contains 35% to 85% vanadium by weight, with the remainder being iron. The alloy is designed to introduce vanadium efficiently into molten steel, improving its hardness, toughness, tensile strength, and resistance to wear and fatigue.

Ferrovanadium is made by reducing vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅)—the most common vanadium compound—with iron in the presence of a reducing agent such as silicon, aluminum, or carbon. This process is carried out in an electric arc furnace or aluminothermic reactor, where the vanadium oxide reacts with the reducing metal to form ferrovanadium and slag. The molten alloy is then cast into ingots, crushed, and sized for use in steelmaking.

When added to steel, vanadium forms hard, stable carbides and nitrides within the microstructure. These compounds refine the grain size and prevent dislocation movement, dramatically increasing the steel’s strength and resistance to deformation, even at high temperatures. As a result, ferrovanadium is widely used in high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steels, tool steels, spring steels, and high-speed steels.

In construction and automotive industries, ferrovanadium helps produce steel that is lighter but stronger, allowing for reduced material usage without sacrificing performance—a key advantage in bridges, pipelines, rebar, and vehicle frames. In aerospace and defense applications, vanadium’s ability to enhance temperature stability and fatigue strength makes ferrovanadium-containing alloys suitable for jet engines, landing gear, and armor plating.

Ferrovanadium typically comes in two standard grades:

- FeV 80 – containing about 78–82% vanadium, commonly used in high-strength steels.

- FeV 50 – containing about 45–55% vanadium, used where lower vanadium content is sufficient.

Aside from steelmaking, small amounts of ferrovanadium are also used in titanium–vanadium–aluminum alloys, which are essential in aerospace engineering.

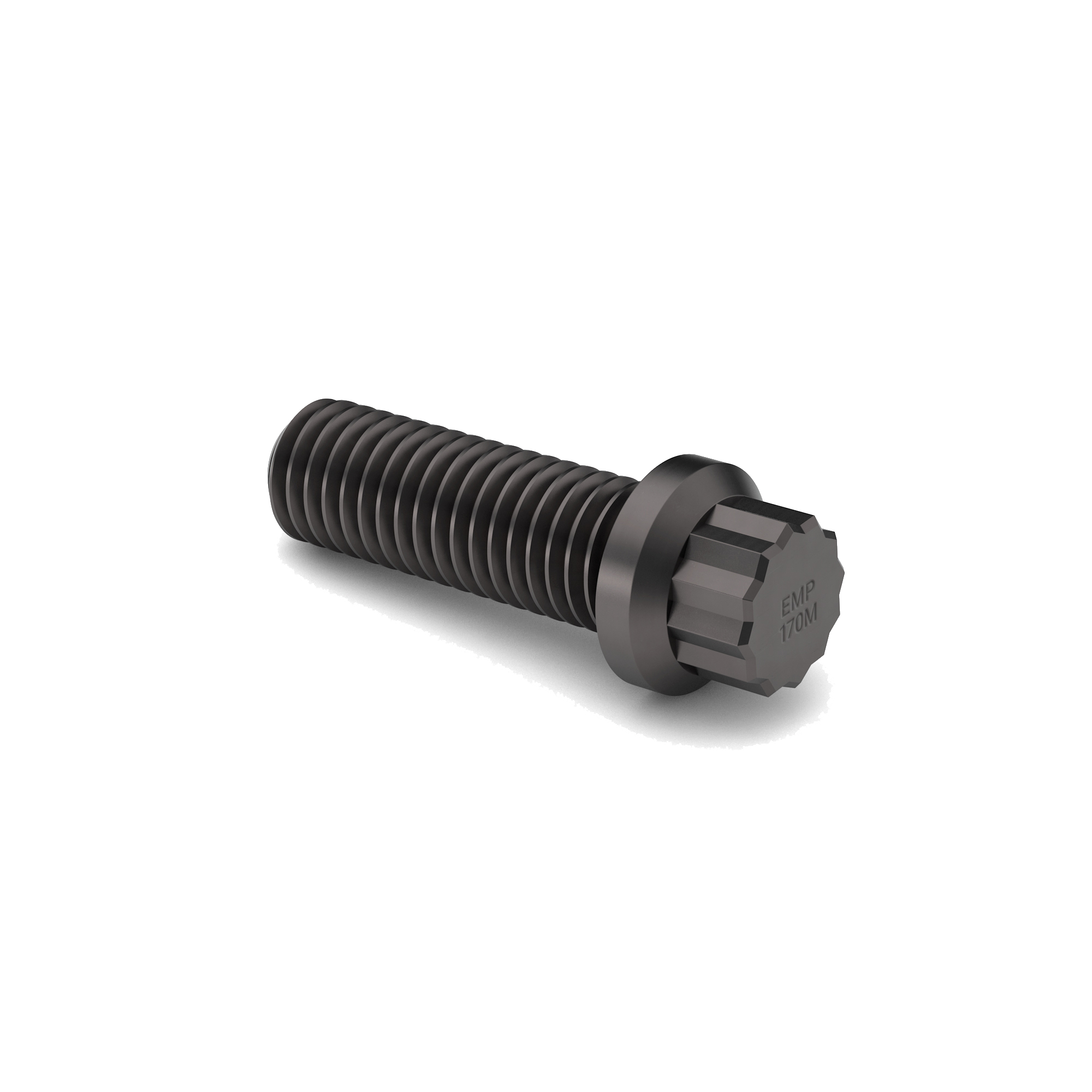

Ferry Cap Screw

A Ferry Cap screw is a high-strength fastener, also known as a 12-point flange screw or bolt. It is characterized by its distinctive 12-point head, which provides a larger gripping surface compared to standard hexagonal or internal hex fasteners. This design feature allows for the application of significantly higher torque during tightening, ensuring a more secure and reliable connection. An integrated flange at the base of the head acts as a built-in washer, distributing the clamping pressure evenly across the bearing surface and eliminating the need for a separate washer. The fastener is driven using a standard 12-point socket or pneumatic wrench.

The name "Ferry Cap screw" originates from its original manufacturer, the Ferry Cap & Set Screw Company, which was founded in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1907. These specialized screws are manufactured from high-quality materials, such as alloy or stainless steel, and are capable of withstanding extreme conditions, including high stress, vibration, and temperature. Some versions of these fasteners are rated with tensile strengths exceeding 170,000 psi, making them suitable for demanding, heavy-duty applications.

Ferry Cap screws are widely used across various industries that require exceptional strength and durability, often in confined spaces where access is limited. Common applications include high-stress environments such as diesel engines, aerospace engineering, and off-road vehicle suspensions. They are also utilized in the oil and gas industry for high clamping load applications, in the construction industry, and within heavy-duty earth-moving machinery. Furthermore, their robust nature makes them ideal for power generation, marine, and military applications where reliable fastening is critical.

AKA: 12 Point Flange Screw

Fillister Head Screw

A fillister head screw is a type of machine screw that has a cylindrical, slightly rounded head with a deep, straight slot for a flat-blade screwdriver. The head is taller and narrower than that of a round-head or pan-head screw, which provides more strength in the head and allows for a deeper slot that resists cam-out during tightening.

Fillister head screws are often used where a stronger head-to-shank connection is needed or where the screw head must sit above the surface for accessibility. Their deep slot makes them easier to drive with hand tools, especially in older equipment or when higher torque is required.

They are commonly found in machinery, electrical equipment, and precision instruments, as well as in restoration of vintage machines and electronics, where they were historically more popular before pan-head and Phillips-head screws became standard.

Fin Neck Bolt

A fin neck bolt is a type of carriage-style bolt designed with fins or ribs under the head that bite into wood, soft metals, or other ductile materials to prevent the bolt from turning as the nut is tightened. Instead of having a smooth, round underside like a standard carriage bolt, the fin neck bolt has one or more protruding wedge-shaped fins that embed themselves into the mating surface. This gives the bolt anti-rotation capability without requiring a square neck or a special recess.

How it works

When the bolt is driven or tightened, the fins under the head cut into or deform the surface, locking the head into place. This allows torque to be applied to the nut on the opposite end without needing a tool on the bolt head—making it especially useful in one-sided access applications.

Where fin neck bolts are used

They are commonly used in:

- Thin sheet metal assemblies

- Automotive and appliance manufacturing

- Electrical enclosures and stamped components

- Furniture assembly

- Any application where a traditional square-neck carriage bolt might distort the material

Because the fins create a mechanical lock, fin neck bolts help maintain alignment and resist loosening in applications involving vibration or shear forces.

Materials and finishes

Fin neck bolts are typically made from:

- Low-carbon or medium-carbon steel

- Stainless steel

- Zinc-plated or coated steel for corrosion resistance

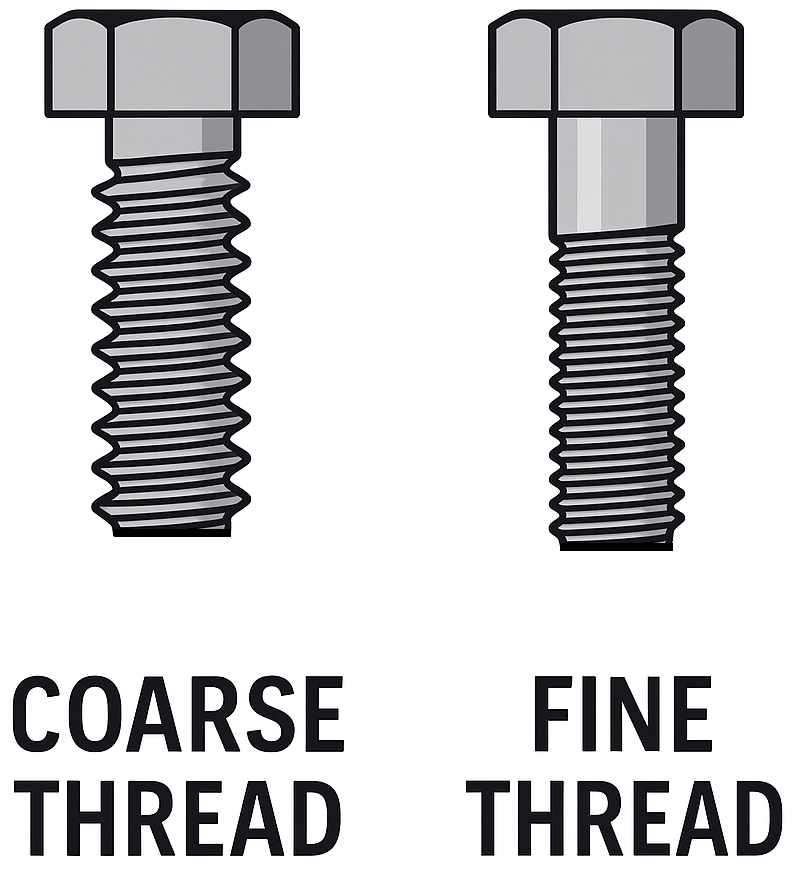

Fine Thread

A fine thread has more threads per unit length than a coarse thread, making them shallower and more closely spaced. This design provides greater strength, better vibration resistance, and more precise adjustment, though it takes longer to assemble and is more prone to damage or cross-threading.

They are commonly used in automotive, aerospace, and high-stress machinery applications, especially where precision and durability are critical.

Finished Hex Nut

A finished hex nut is a standard six-sided nut used to fasten bolts and screws in a wide variety of general-purpose applications. It is called "finished" to distinguish it from other types of nuts, such as heavy hex nuts, jam nuts, or lock nuts.

Finishing Nails

A finishing nail is a type of nail designed for use in finish carpentry, where the goal is to fasten materials with a minimal visible nail head for a cleaner, smoother appearance.

Finishing Washer

A finishing washer is a type of decorative washer used primarily to enhance the appearance of a fastened joint while also providing some functional benefits. It is designed to give a clean, polished look by covering large holes or irregular surfaces around bolts, screws, or rivets.

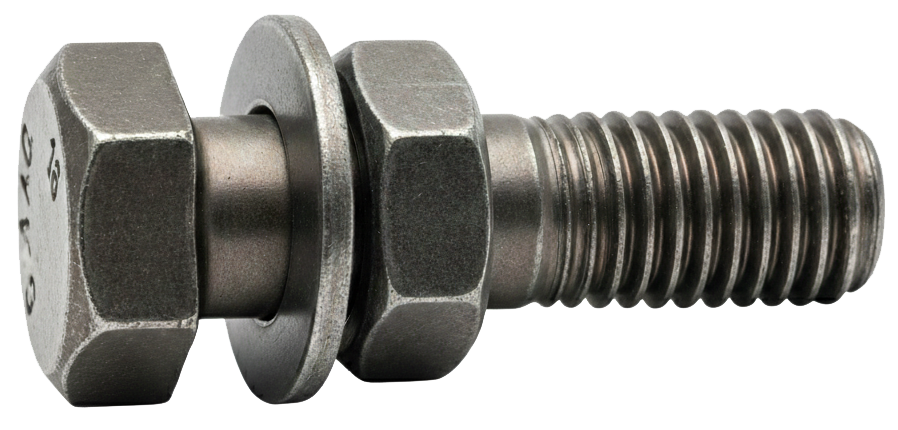

Flange Bolt

A flange bolt is a type of bolt that has an integrated flange—a wide, washer-like base—just below the bolt head. This flange distributes the clamping load over a larger surface area, which helps to reduce the need for a separate washer and provides a more secure fastening.

Flat Carriage Bolt

Flat Head Carriage Bolts feature a low-profile head, which allows the fastener to be used in applications requiring minimal clearance. The low-profile design ensures a flush finish and reduces interference with surrounding components. This fastener also features a square section beneath the head, preventing the fastener from turning when the nut is tightened. Flat Head Carriage Bolts are commonly used in the construction of wood or steel garage doors and are used in a variety of other applications and areas across the fastener industry.

Flat O-Rings

A flat O-ring is a type of sealing ring with a flat cross-section rather than the traditional round (torus) shape of a standard O-ring. It combines the sealing function of an O-ring with the low-profile characteristics of a washer or gasket.

Flat Sleeve Anchor

A flat sleeve anchor is a pre-assembled mechanical expansion anchor for masonry that uses a countersunk (flat) head so the fastener sits flush with the fixture. Like other sleeve anchors, it consists of a threaded fastener, an expansion sleeve, and a cone. When you tighten the screw or bolt, the cone is drawn into the sleeve and forces it to expand against the walls of the drilled hole, creating frictional hold.

Because the sleeve expands along much of its length, flat sleeve anchors work in solid concrete, brick, and many hollow masonry units, making them a versatile medium-duty choice. The flat, countersunk head is used when you want a flush finish on plates, brackets, thresholds, door frames, handrail bases, or hardware where a protruding hex head would be undesirable.

Installation is straightforward: drill a hole the same diameter as the anchor, clean out dust, place the anchor through the countersunk fixture hole, drive it into the base material to the required embedment, then tighten to expand the sleeve. They’re commonly made from zinc-plated carbon steel for dry interiors or 304/316 stainless for corrosion resistance.

Compared with wedge anchors, sleeve anchors are easier to install and more forgiving in mixed masonry, but they generally have lower load capacities and aren’t typically rated for cracked concrete or seismic/sustained tension unless specifically tested. For best results, follow the manufacturer’s spacing, edge-distance, and torque guidance.

Flat Washer

A flat washer is a thin, flat, circular piece of metal (or other materials like plastic) with a hole in the center. It is used in conjunction with fasteners such as bolts, screws, and nuts to distribute the load of the fastener over a larger surface area, prevent damage to the material being fastened, and reduce the likelihood of the fastener loosening over time.

Flat Washer DIN 125A

A Flat Washer DIN 125A is a standard type of flat washer that conforms to the DIN 125 specification, which is a widely recognized German industrial standard for flat washers. These washers are used in conjunction with bolts, screws, and nuts to distribute the load of the fastener, prevent damage to the surface, and reduce the chance of loosening due to vibration. The DIN 125A flat washer has a simple, flat, circular design with a central hole, and is typically used in general mechanical, industrial, and construction applications.

Flexible Roller Eye Bolt

A Flexible Roller Eye Bolt is a specialized type of lifting or anchoring bolt designed to handle loads that may shift or move during operation. Unlike a standard eye bolt, which has a rigid, fixed loop, a flexible roller eye bolt incorporates a rotating or pivoting eye that can move slightly to accommodate angular loads, vibration, or directional changes in tension. This flexibility helps prevent bending stresses on the shank and reduces the risk of fatigue failure, especially in dynamic or off-angle lifting applications.

The “roller” aspect typically refers to an internal bearing or bushing mechanism that allows the eye portion to rotate smoothly under load. This feature helps maintain alignment of the attached cable, chain, or hook, distributing force evenly and reducing wear on both the bolt and the attached lifting hardware. Flexible roller eye bolts are commonly used in material handling systems, marine rigging, cranes, conveyors, and heavy machinery where movement or vibration occurs during operation.

In essence, a flexible roller eye bolt combines the strength of a traditional lifting bolt with the adaptability of a swivel or pivoting head, offering a safer and more durable solution for multi-directional load conditions.

Floorboard Screw

A floorboard screw is a wood screw designed for fixing timber floorboards (or subfloor panels) to joists without squeaks or loosening. Unlike general-purpose wood screws, it’s optimized to pull boards tight, sit flush, and resist back-out over time under foot traffic and vibration.

Typical features include a countersunk or trim head (often with cutting ribs under the head so it self-countersinks), a high-grip drive such as Torx/Pozi to reduce cam-out, and a partial coarse thread so the top (unthreaded) shank clamps the board hard to the joist. Many use twin-start or serrated threads for fast drive, and a Type-17 slash point or self-drilling tip to reduce splitting—especially important near tongue-and-groove edges. Materials are usually case-hardened carbon steel with zinc/yellow or ceramic coatings for corrosion resistance; stainless is used in damp areas.

Sizes vary by flooring, but common diameters are about 3.5–5.0 mm (#6–#10) with lengths 40–65 mm (1⅝–2½ in.); a good rule is ~2.5× the board thickness. For plywood/OSB subfloors, heavier “subfloor screws” (bugle head, #8–#10, 50–75 mm) are used to stop nail-pops and squeaks.

Installation tips: pre-drill hardwoods and near board ends; drive two screws per joist line to prevent cupping (stay ~10–15 mm from edges); for tongue-and-groove floors you can angle screws through the tongue to hide the heads; let the ribs seat the head flush—don’t over-torque—and use adhesive where specified for a squeak-free floor.

Flooring Nails

Flooring nails are specially designed fasteners used to secure wood flooring—such as hardwood or engineered planks—to a subfloor. They are engineered to provide strong holding power while minimizing damage to the wood, especially in tongue-and-groove flooring installations.

Flux

In steelmaking, a flux is a material added to the molten metal or furnace charge to help remove impurities such as silica (SiO₂), phosphorus (P), sulfur (S), and alumina (Al₂O₃) from the ore, scrap, or additives. Fluxes work by chemically combining with these unwanted substances to form a molten slag, which floats on top of the metal and can be easily removed.

Common flux materials include limestone (CaCO₃), dolomite (CaMg(CO₃)₂), fluorspar (CaF₂), and lime (CaO). These substances melt at high temperatures and react with impurities to form stable, low-density compounds that separate from the molten steel.

Here’s how flux works in the steelmaking process:

- Addition to the furnace: Flux is introduced into the blast furnace, basic oxygen furnace (BOF), or electric arc furnace (EAF) along with iron ore, coke, and other raw materials.

- Chemical reaction: Under high heat, the flux decomposes (e.g., limestone breaks down into calcium oxide (CaO) and carbon dioxide (CO₂)). The CaO then reacts with acidic impurities such as silica to form calcium silicate (slag).

- Slag formation: The molten slag collects at the top of the steel bath, trapping non-metallic impurities and helping to protect the molten metal from oxidation.

- Removal: Once the slag solidifies, it can be removed, leaving behind cleaner, higher-quality steel.

Fluxes also serve secondary purposes: they regulate furnace temperature, protect refractory linings, and improve the fluidity of slag to ensure complete separation of impurities.

Flywheel Bolt

A flywheel bolt is a high-strength, precision fastener used to secure a flywheel to the crankshaft of an engine. Because the flywheel handles major forces—including rotational inertia, vibration, and the transfer of power between the engine and transmission—its bolts must withstand extreme cyclic loading, shear forces, and torsional stress without loosening or failing.

Flywheel bolts are usually made from alloy steel with very high tensile strength and are often heat-treated to improve fatigue resistance. Many engines use torque-to-yield (TTY) flywheel bolts, which are tightened past their elastic limit so they stretch slightly to maintain clamping force. These are generally one-time-use bolts because once stretched, they cannot reliably be reused. Whether TTY or conventional, flywheel bolts typically require precise tightening sequences, specific torque values, or torque-plus-angle procedures because the flywheel must remain perfectly centered and rigidly attached.

To prevent loosening under vibration, flywheel bolts often incorporate threadlocker, special flange heads, fine threads, or hardened washers. In performance engines or heavy-duty applications, the bolts may be upgraded to ARP-style high-performance fasteners, which provide even greater clamping force and fatigue strength.

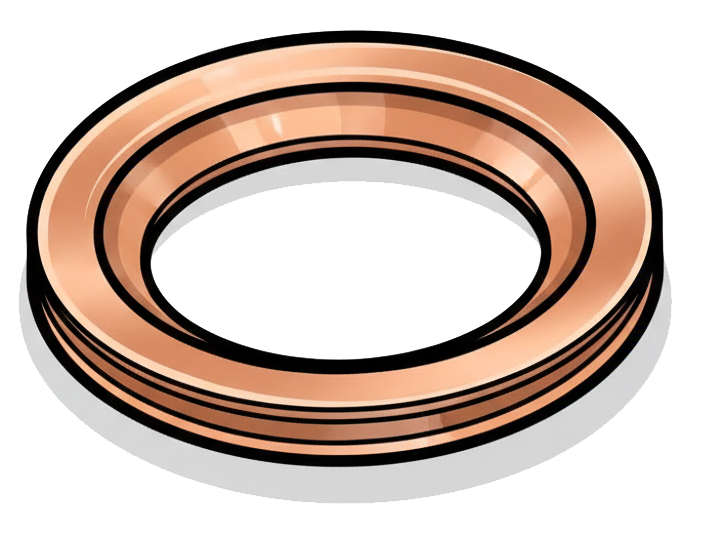

Folded Copper Washer

A folded copper washer is a sealing washer made from a strip of copper that has been bent or folded over itself, creating a double-layered structure rather than a single solid disc. This fold gives the washer a U-shaped or crimped cross-section, making it more compressible and flexible than a standard flat copper washer.

Because copper is naturally soft and ductile, the folded design allows the washer to deform under bolt load, letting it conform more tightly to mating surfaces and create a better fluid-tight seal. This makes it especially useful in applications that experience vibration, temperature changes, or slight surface irregularities—conditions where a solid washer may not compress enough to maintain sealing integrity. Folded copper washers are often used in hydraulic systems, brake and fuel fittings, oil systems, and HVAC or refrigeration connections.

Unlike a single-layer solid copper washer, which behaves more like a rigid spacer or crush ring, a folded copper washer behaves more like a gasket. The layered structure gives it greater resiliency and sealing performance while still retaining the corrosion resistance and thermal conductivity associated with copper.

Folds

Irregularities, laps, or creases in the material of a fastener, typically formed during manufacturing processes such such as cold heading, forging, or thread rolling. These imperfections occur when material flows improperly and folds over itself, rather than flowing smoothly. Folds can appear under the head, along the shank, or in the threads. They are a significant concern because they can act as stress concentrators, weakening the fastener's structural integrity and potentially leading to premature fatigue or fracture under load.

Forming Crack

A crack that develops in a fastener's material during its manufacturing process, specifically during shaping operations such as cold heading, forging, or thread rolling. These cracks typically occur when the material is subjected to stresses beyond its formability limits, or due to improper tooling and process parameters. Unlike cracks that develop during service, forming cracks are inherent manufacturing defects that can significantly reduce the fastener's load-bearing capacity and potentially lead to premature failure.

Four-Point Socket

A four-point socket—also known as a square socket—is a type of wrench or drive socket designed to fit fasteners that have a square-shaped head or nut rather than the more common hexagonal (six-point) design. Instead of six internal contact points, the four-point socket has four flat internal surfaces arranged at 90° angles, forming a perfect square opening that mates precisely with the square corners of a matching fastener or drive.

These sockets are primarily used for square-head bolts, pipe plugs, and set screws, which are common in industrial machinery, plumbing, vintage equipment, and heavy-duty maintenance applications. Because the socket engages the flat sides of the square head rather than its corners, it provides a secure, non-slip grip and helps distribute torque evenly, reducing the risk of rounding or damaging the fastener.

The four-point configuration also allows for 90° engagement increments, meaning the user can reposition the wrench more frequently in tight spaces—especially useful when working with ratchets or breaker bars. The simplicity of the square interface makes it ideal for high-torque applications and older mechanical systems where hex fasteners weren’t yet standard.

In addition to their use with fasteners, four-point sockets are an integral part of socket wrench sets, as the female square socket end is what connects to the male square drive of a ratchet handle (commonly in ¼″, ⅜″, ½″, ¾″, or 1″ sizes). This means that even modern hex or 12-point sockets have a four-point square drive interface at the back—an evolution of the same concept.

AKA: Square Socket

Free Iron

Small particles of unalloyed (pure) iron that become embedded or smeared onto the surface of stainless steel during manufacturing processes such as machining, forming, or handling. Because these particles are not part of the stainless steel alloy, they can oxidize (rust) when exposed to moisture or air, leading to localized corrosion or staining if not removed through the chemical treatment process of passivation.

Free-Cutting Steel

Free-cutting steel, also known as free-machining steel, is a specially formulated type of carbon or alloy steel designed to enhance machinability—that is, to make cutting, drilling, turning, or milling operations faster and smoother with minimal tool wear. These steels contain additives such as sulfur, lead, phosphorus, or selenium that help the metal break into small chips during machining, reduce friction, and prevent built-up edge formation on cutting tools.

In standard steels, the material tends to produce long, continuous chips that tangle around tools, generate excess heat, and cause premature tool wear. Free-cutting steels overcome these problems by creating short, easily broken chips, which improves machining speed, surface finish, and tool life. The tradeoff, however, is that these steels often exhibit slightly reduced toughness, ductility, and weldability due to the presence of non-metallic inclusions from the additives.

The most common example is free-cutting mild steel (such as AISI 12L14), which contains small amounts of lead (Pb) and sulfur (S). During machining, the lead acts as a lubricant, allowing tools to slide smoothly through the material, while sulfur forms manganese sulfide (MnS) inclusions that help chips break apart cleanly. Other variants use selenium or tellurium for similar effects, especially when lead is avoided for environmental or health reasons.

Chemically, a typical free-cutting carbon steel might have a composition such as:

- 0.10–0.45% carbon (depending on strength requirements)

- 0.15–0.35% sulfur

- 0.85–1.00% manganese

- 0.15–0.35% lead (if leaded type)

Free-cutting steels are widely used in high-volume production environments, especially in automatic lathes, CNC machines, and screw machines, where speed and consistency are critical. They’re common in parts like fittings, bushings, fasteners, pins, shafts, and precision machined components that require high dimensional accuracy but not extreme mechanical strength.

AKA: Free-Machining Steel

Fretting

Fretting is a type of wear and surface damage that occurs when two contacting materials experience repeated small-amplitude oscillatory motion—typically vibration or micro-sliding—under load. Even though the movement between the surfaces is very slight (often less than 100 microns), it causes abrasion, oxidation, and material degradation over time.

This phenomenon commonly occurs in bolted joints, splines, bearings, shafts, and structural assemblies, where surfaces are pressed together but subjected to vibration or cyclic stress. As the materials rub microscopically, the protective oxide films are repeatedly broken and re-formed, producing fine metallic debris that oxidizes quickly. This results in reddish-brown or black debris (often called fretting corrosion) and pitted, roughened contact surfaces.

Fretting can lead to serious problems such as loss of preload in fasteners, fatigue cracking, surface weakening, and joint loosening. It’s especially problematic in aerospace, automotive, and machinery applications where vibration and precision contact are unavoidable.

Preventing fretting involves minimizing micro-movements and maintaining stable contact conditions—often through increased clamp load, surface coatings, lubricants, or using materials with higher hardness or corrosion resistance.

Friction Grip

Friction grip refers to the clamping force created between two surfaces when a bolt or fastener is tightened, causing friction that resists relative movement between the connected parts. In a friction grip joint, the load is transmitted through friction at the interface of the clamped materials, rather than through the bolt shank bearing directly against the holes.

When a high-strength bolt (such as a structural bolt in steel construction) is tightened to a specific torque, it stretches slightly and creates a large clamping force on the joint. This force presses the plates together tightly enough that the friction between their surfaces can resist applied shear or slip forces. As long as the external load does not exceed the frictional resistance, the bolt itself experiences only tension, not shear.

Friction grip connections are commonly used in structural steelwork, bridges, cranes, and heavy machinery, where maintaining rigidity and minimizing movement are critical. They prevent fretting, fatigue, and bolt loosening caused by vibration or dynamic loading. The effectiveness of such joints depends on factors like bolt tension, surface condition (roughness or treatment), and coefficient of friction between the mating parts.

Friction Grip Bolt

A friction grip bolt is a type of high-strength structural bolt designed so that the joint is held together by friction between the clamped surfaces, rather than by the bolt bearing directly against the hole.

When tightened to a specified preload, the bolt generates a strong clamping force that presses the connected plates together. The friction between these surfaces resists movement, meaning the load is transferred through surface friction instead of shear on the bolt shank. This reduces the risk of bolt slip, loosening, or fatigue under vibration. Friction grip bolts are usually high-tensile fasteners, often conforming to standards like EN 14399 or ASTM A325/A490, and are tightened with torque-control or direct-tension methods to achieve the necessary clamping force.

They are commonly used in bridges, steel buildings, cranes, towers, and other critical load-bearing structures where slip resistance and long-term joint integrity are essential. By relying on friction rather than shear, friction grip bolts provide more reliable and durable connections in dynamic or high-stress environments.

FRP Fasteners

FRP fasteners are fasteners made from Fiber-Reinforced Plastic (FRP)—a composite material consisting of a polymer matrix (such as polyester, vinyl ester, or epoxy resin) reinforced with fibers like glass (fiberglass), carbon, or aramid (Kevlar). These fasteners are designed as lightweight, non-metallic alternatives to traditional steel or aluminum bolts, nuts, and washers, particularly in environments where corrosion, electrical conductivity, or magnetic interference are concerns.

Structurally, FRP fasteners are molded or machined into various standard shapes—bolts, nuts, studs, washers, threaded rods, and spacers—and can be made with continuous glass fiber reinforcement to enhance tensile strength. Despite being much lighter than metal, they exhibit impressive mechanical strength, chemical resistance, and dimensional stability, even under harsh conditions.

The key advantages of FRP fasteners include:

They are non-corrosive, making them ideal for marine, chemical processing, wastewater, and outdoor structural applications where metal fasteners would rust or degrade. They are non-conductive, so they’re commonly used in electrical, electronic, and telecommunications installations to prevent short circuits or arcing. They are also non-magnetic, useful in MRI rooms, radar equipment, and sensitive scientific instruments.

While FRP fasteners don’t match the ultimate strength of high-grade steel, they perform exceptionally well in moderate load-bearing, chemical, and dielectric applications. In some cases, they are paired with FRP or composite structures to maintain uniform material performance and avoid galvanic corrosion.

Full Thread

A full thread fastener is one in which the threaded portion extends along the entire length of the shank, from just below the head to the end of the fastener. Unlike a partial thread bolt or screw, which has an unthreaded grip section (shank) near the head, a full thread fastener maximizes the amount of engaged threads in the mating material.

Full Thread Stud

A full thread stud is a cylindrical metal rod that is fully threaded along its entire length, with no unthreaded sections. It is designed to be used in various fastening and assembly applications, where both ends of the stud are screwed into nuts or other threaded components. Full thread studs are commonly used to join two parts or materials together in high-strength, high-tension, or precision applications.

Fusible Plug

A fusible plug is a thermal-safety device used in boilers, air compressors, pressure vessels, refrigeration systems, fire-suppression equipment, and other industrial systems that generate heat and pressure. It is typically made from brass, bronze, or steel and contains a core of low-melting-point alloy—often tin, lead, bismuth, or a eutectic blend—engineered to liquify at a specific, predetermined temperature. Under normal operating conditions, this alloy core remains solid and keeps the system sealed. But when temperatures rise to an unsafe level, usually somewhere between 212°F and 550°F (100°C to 288°C) depending on the application, the alloy melts. This melting action opens a passage through the plug that allows pressure, steam, gas, or liquid to escape.

The primary purpose of a fusible plug is to provide a passive, mechanical fail-safe that prevents catastrophic failure. In a steam boiler, for example, overheating caused by low water levels can weaken the metal shell and lead to an explosion. The fusible plug melts before this can happen, releasing steam and signaling the operator that dangerous conditions have developed. In air compressors, it prevents tank rupture by venting pressure when excessive heat indicates a malfunction. Because it functions solely on temperature—not electricity, sensors, or software—the device is always active and provides protection even during power loss or equipment failure.

By melting at a precise temperature, the plug offers reliable protection against heat-related accidents, including boiler explosions, compressor tank failures, runaway thermal conditions, and fire hazards. Its simplicity, reliability, and automatic response make it an essential safety feature in many industrial systems, especially those where excessive heat is a sign of imminent danger.