Resources

Glossary

O-Ring

An O-ring is a circular, donut-shaped sealing element made from an elastic material such as rubber, silicone, nitrile, or fluorocarbon (like Viton). It is designed to fit into a groove and be compressed between two or more parts to create a tight, leak-proof seal. O-rings are used to prevent the escape of fluids or gases and are one of the most common and effective types of mechanical seals in engineering.

When an O-ring is installed and pressure is applied, it deforms slightly to fill the space between the mating surfaces, blocking any potential leakage paths. This makes O-rings ideal for both static seals (where parts don’t move relative to each other, such as in pipe fittings) and dynamic seals (where motion occurs, such as in hydraulic cylinders or rotating shafts).

O-rings are widely used because they are simple, inexpensive, compact, and reliable. Their performance depends on factors like material compatibility with the fluid being sealed, temperature range, pressure, and groove design.

OEM

OEM stands for Original Equipment Manufacturer. It refers to a company that designs and produces parts, components, or products that are used in another company’s final product—often without being sold directly to end users under the OEM's own brand.

In automotive and industrial contexts:

- OEM parts are the components originally installed on a vehicle or machine when it was built.

- They are manufactured to the original specifications, typically by the same company (or a contracted supplier) that supplied the parts during production.

OEM is often contrasted with aftermarket parts, which are produced by third-party manufacturers not involved in building the original product.

Short example:

If Toyota installs a Denso-made sensor in a factory-built car, Denso is the OEM for that part, even though Toyota is the vehicle manufacturer. If someone later buys a cheaper replacement made by another company, that's an aftermarket part.

Ogee Washer

An ogee washer is a heavy-duty washer with a thick, curved (S-profile/“ogee”) face and a large bearing surface. Typically cast or malleable iron—often hot-dip galvanized—it sits under a nut or bolt head to spread load over wood and resist crushing or pull-through.

You’ll see them in timber framing, docks, bridges, utility/pole line work, and other structural wood connections where a standard flat washer is too small. The ogee contour lets the washer seat firmly on uneven wood and provides a traditional look. They’re sometimes called malleable iron ogee washers, cast ogee washers, or timber washers.

One-Way Screw

A one-way screw is a type of tamper-resistant fastener designed so it can be installed with a standard flat-blade screwdriver or similar tool, but cannot be easily removed once in place. The unique feature of this screw is its specially shaped drive slot, which engages with a driver in the tightening direction but causes the tool to slip in the loosening direction. This makes the screw well suited for applications where security and permanence are desired over serviceability.

In terms of design and construction, the head of a one-way screw resembles a traditional slotted screw, but with sloped or ramped slot edges. When a screwdriver turns clockwise, the tool fits securely into the slot and drives the fastener into the material. If torque is applied counterclockwise, however, the sloped edges prevent engagement, and the screwdriver slips, stopping removal. These screws are commonly made from materials such as steel, stainless steel, or brass, and they come in various head styles, including countersunk, round, or pan heads.

The purpose and function of a one-way screw is to provide tamper resistance. Once installed, the screw cannot be removed using conventional tools, which helps prevent theft, vandalism, or unauthorized disassembly. This makes them an inexpensive and effective solution for situations where permanence and security are critical.

Common applications include public safety and infrastructure, such as securing license plates, bathroom fixtures, and public signage. They are also used in security installations, including locks, enclosures, and hardware where tampering must be minimized. In consumer products, one-way screws are sometimes used in electronics and appliances to restrict user access. In construction, they may fasten panels, fencing, or other components intended to remain fixed permanently.

The advantages of one-way screws are their simplicity, low cost, and ease of installation since they can be driven with a standard flat-blade screwdriver. They offer a clean and unobtrusive appearance and are available in multiple head styles and materials.

There are, however, limitations. One-way screws are difficult or impossible to remove without damaging the screw or the surrounding material. Removing them usually requires special extraction tools or destructive methods. They are not suitable for applications requiring regular maintenance or disassembly. Additionally, while they resist casual tampering, determined individuals with specialized tools can still defeat them, so their security is moderate rather than absolute.

Outside Diameter (OD)

Outside diameter (OD) is the maximum external width of a cylindrical or round part, measured as the distance across the outside surface through the centerline. It is the standard way to specify the “outer size” of components such as rod, wire, tube/pipe, sleeves, bushings, and many fastener features.

For fasteners, OD commonly refers to the shank diameter of a bolt or screw, the outer diameter of a nut or washer, the outside diameter of a spacer, or the major diameter of an externally threaded part (the largest diameter measured crest-to-crest). OD is critical for ensuring proper fit in holes and counterbores, maintaining required bearing surface area, controlling clearances, and meeting dimensional standards and tolerance requirements.

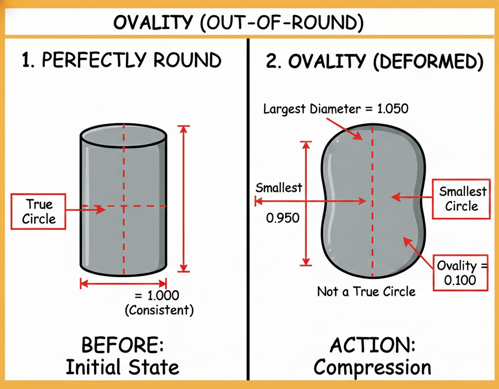

Ovality

Ovality is the amount a feature that should be perfectly round—such as a shank diameter, hole, tube, bushing, or thread pitch diameter—deviates into an oval (out-of-round) shape. Instead of having one true diameter everywhere, the part has a largest measured diameter and a smallest measured diameter depending on the measurement direction.

Ovality is typically quantified as the difference between those values, for example ovality = Dmax − Dmin (sometimes reported as a percentage of the nominal diameter). In fasteners and precision hardware, ovality matters because it can affect fit and assembly (clearance holes, bushings, sleeves), thread engagement (especially in tight tolerance threads), bearing/contact patterns, and the repeatability of torque-to-tension behavior when components don’t contact uniformly. It can be introduced by manufacturing processes (rolling, drawing, bending, plating buildup, heat treatment distortion) or by service loads that plastically deform a part in one direction.

Overtapping

Overtapping refers to the process of tapping internal threads to a slightly larger-than-standard diameter, so that once plating or coatings are applied, the threads return to the proper final size and allow the bolt to fit correctly. Without overtapping, coatings such as zinc, phosphate, paint, e-coat, galvanizing, or thermal spray add thickness to the thread flanks, reducing the effective pitch diameter and causing fasteners to bind, install with excessive torque, or fail to seat properly. Overtapping prevents this by cutting the threads oversize before finishing, ensuring that after coating, the final dimensions match the intended fit.

In fastener manufacturing and machining, overtapping is especially important when a threaded hole will see heavy coatings or when a smooth-running assembly is required. Thread classes and tolerances can be adjusted intentionally, such as specifying larger H-limit taps in Unified threads or oversize tolerance grades in metric threads, to achieve the correct post-process pitch diameter. The goal is not to create a loose thread but to maintain proper functional engagement as if the coating were not present.

Overtapping is also used in applications involving thread-forming fasteners, which displace material rather than cutting it. A slightly oversized starting thread or pilot hole reduces deformation forces and prevents galling or stripping during installation. In all cases, overtapping ensures the threaded interface performs as designed, maintaining correct torque, load capability, and assembly reliability despite dimensional changes caused by coatings or forming processes.

Oxidation

Oxidation is a chemical reaction in which a material—typically a metal—loses electrons when it comes into contact with oxygen or another oxidizing agent, often forming an oxide layer on its surface. In simple terms, it’s the process that causes metals like iron to rust, copper to develop a green patina, or aluminum to form a thin protective film.

When a metal is exposed to air or moisture, oxygen molecules react with the atoms on its surface, creating metal oxides. For example, when iron reacts with oxygen and water, it forms iron oxide (rust), which is porous and flaky, allowing the corrosion to continue deeper into the metal. In contrast, metals such as aluminum, chromium, and titanium form stable, tightly adherent oxide layers that protect the underlying metal from further oxidation—this property is called passivation.

Oxidation doesn’t always cause damage; in many cases, it’s intentionally used to enhance corrosion resistance or surface appearance (as in anodizing aluminum or black oxide coatings on steel). However, uncontrolled oxidation can weaken materials, reduce conductivity, and lead to structural failure over time.