Resources

Glossary

Superconductivity

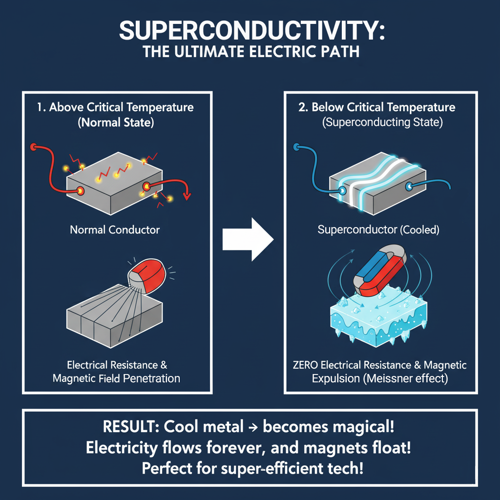

Superconductivity is a phenomenon in which a material, when cooled below a certain critical temperature, suddenly loses all electrical resistance and allows electric current to flow indefinitely without any energy loss. At the same time, the material also expels magnetic fields from its interior—a property known as the Meissner effect. Together, these two characteristics define a superconducting state, a unique quantum mechanical condition of matter.

In a normal conductor like copper or aluminum, electrical resistance arises because moving electrons collide with atoms and imperfections, converting some electrical energy into heat. However, in a superconductor, once the material is cooled below its critical temperature (Tc), these collisions effectively disappear. The electrons pair up into what are called Cooper pairs, named after physicist Leon Cooper. These paired electrons move through the atomic lattice in a coordinated quantum state, which allows them to flow without scattering—hence, without resistance.

The Meissner effect is equally remarkable: when a material becomes superconducting, it actively expels magnetic fields from its interior, causing a magnet to levitate above it. This happens because the superconductor generates surface currents that exactly cancel the applied magnetic field within the material. This behavior distinguishes superconductors from mere perfect conductors, since the Meissner effect demonstrates a true phase change in the material’s electromagnetic properties.

Superconductivity occurs in a range of materials, including pure metals like mercury (the first discovered superconductor, in 1911 by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes), metal alloys, and ceramic high-temperature superconductors. Traditional (low-temperature) superconductors, such as lead or niobium-titanium, require cooling with liquid helium to temperatures near absolute zero (around 4 K). High-temperature superconductors—such as yttrium barium copper oxide (YBCO)—can operate at higher critical temperatures, around 77 K, allowing cooling with liquid nitrogen, which is more economical and practical.

Superconductors have profound technological applications. They are essential in MRI machines, maglev trains, particle accelerators, fusion reactors, and superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs) used for ultra-sensitive magnetic field detection. They are also being researched for lossless power transmission, high-efficiency motors, and quantum computing.