Resources

Glossary

Impact Wrench

An impact wrench is a power tool that delivers high torque with little effort by the user. It uses a hammer-and-anvil mechanism that stores energy in a rotating mass and then releases it in short, powerful bursts to the output shaft. This impact action makes it ideal for loosening or tightening bolts, nuts, and other fasteners that are stuck or require high torque.

Impact wrenches can be powered by compressed air (pneumatic), electricity (corded or cordless battery), or hydraulics, with pneumatic models being the most common in industrial and automotive work. They typically use a square drive (often 1/2 inch) that holds heavy-duty impact sockets designed to withstand vibration and torque. Because the tool delivers torque in bursts rather than continuously, it is highly effective at removing rusted fasteners, tightening bolts quickly, and reducing operator fatigue. Common applications include automotive repair (like removing lug nuts), construction, heavy equipment maintenance, assembly lines, and industrial operations.

Imperial Measurement

Imperial measurement refers to the system of weights and measures that originated in the British Empire and is still used primarily in the United States, the United Kingdom (in limited contexts), and a few other countries. It is a non-metric system based on historical units such as the inch, foot, yard, and mile for length; the ounce, pound, and ton for weight; and the pint, quart, and gallon for volume.

The Imperial system developed over centuries from older English measurement systems, and it was officially defined in 1824 by the British Weights and Measures Act, which standardized units across the empire. Although most of the world has since adopted the metric system (SI) for science, trade, and daily use, Imperial and U.S. customary units continue to be used in many industries and everyday life, especially in the United States.

Imperial units often use fractions (like ½ inch or ¾ inch) rather than decimals, which can make conversions more complex than in the metric system. For example, instead of centimeters or millimeters, measurements in manufacturing, carpentry, and fasteners might be given in inches and thousandths of an inch (e.g., 0.250 inches = ¼ inch).

In engineering and manufacturing—especially in the fastener industry—imperial dimensions are still common in thread sizes (UNC/UNF), bolt diameters, and wrench sizes, whereas metric measurements are defined in millimeters and millinewtons. For instance, a ¼-20 UNC bolt refers to a ¼-inch diameter bolt with 20 threads per inch.

Inconel

Inconel is a family of nickel–chromium-based superalloys renowned for their exceptional strength, corrosion resistance, and ability to maintain structural integrity at extremely high temperatures. The name “Inconel” is a trademark originally registered by Special Metals Corporation, and it encompasses several specific alloys—such as Inconel 600, 625, 718, and 825—each tailored for different industrial applications.

At its core, Inconel’s strength lies in its nickel content (typically 50–70%), which provides outstanding resistance to oxidation, carburization, and corrosion, even in aggressive chemical or marine environments. The chromium enhances resistance to oxidation and scaling, while elements such as molybdenum, niobium, titanium, and aluminum improve mechanical strength and resistance to creep (deformation under stress at high temperatures).

What makes Inconel particularly valuable is its stability in extreme heat. Unlike many steels that lose strength or become brittle when exposed to high temperatures, Inconel alloys form a stable, adherent oxide layer that protects the surface from further degradation. This allows components made from Inconel to perform reliably at temperatures exceeding 1000°C (1832°F).

Because of these properties, Inconel is used in aerospace and gas turbine engines, where turbine blades, exhaust systems, and combustion liners are exposed to intense heat and corrosive gases. It’s also common in chemical processing, nuclear power plants, heat exchangers, offshore oil and gas equipment, and automotive turbochargers.

Among the common grades:

- Inconel 600 offers excellent resistance to oxidation and corrosion, especially in alkaline environments.

- Inconel 625 is known for superior corrosion resistance and strength due to its molybdenum and niobium content.

- Inconel 718, one of the most widely used, is precipitation-hardenable, providing extremely high tensile and fatigue strength up to about 700°C (1290°F).

In manufacturing, Inconel is notoriously difficult to machine due to its tendency to work-harden rapidly. Specialized cutting tools, slower machining speeds, and high coolant flow are typically required.

Industrial Fasteners Institute

The Industrial Fasteners Institute (IFI) is a North American trade association that represents manufacturers and suppliers of mechanical fasteners—including bolts, nuts, screws, washers, rivets, pins, and related fastening products—along with companies that supply materials, equipment, and services to the fastener industry. The IFI serves as both a technical authority and an advocacy organization, providing standards, educational resources, and representation on issues that affect manufacturers, distributors, and end users across industries such as automotive, aerospace, construction, energy, defense, and general manufacturing.

The purpose of the IFI is to unify the fastener industry by promoting technical knowledge, encouraging consistent production practices, and supporting the proper application of fasteners in critical sectors. The organization acts as a bridge between fastener manufacturers, government agencies, standards organizations, and industries that rely on fasteners. Its mission is to strengthen the industry’s ability to produce safe, reliable, and high-quality products while ensuring that regulations and standards reflect the realities of fastener design and manufacturing.

One of the institute’s primary functions is the development and maintenance of standards. The IFI works closely with national and international bodies such as the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), and the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) to ensure uniformity and consistency in fastener dimensions, mechanical properties, and performance requirements. Beyond its role in standards development, the IFI also provides technical expertise through publications and training. Its most well-known publication is the IFI Fastener Standards Book, often referred to as the “bible of the fastener industry,” which consolidates the industry’s key dimensional and performance standards into a single reference.

The IFI also plays a significant role in education and training for engineers, manufacturers, and distributors. It offers courses, workshops, and online resources designed to improve understanding of fastener specifications, applications, and performance requirements. In addition, the institute engages in advocacy and representation, acting as the voice of the fastener industry in legislative and regulatory matters. It addresses issues such as trade policy, tariffs, and safety regulations that impact fastener production and supply chains.

Membership in the IFI is made up of a broad range of companies. These include fastener manufacturers that produce standard and specialty products, supplier members that provide raw materials, coatings, machinery, tooling, and testing equipment, and service providers that support the industry with engineering, logistics, and quality assurance. Through this diverse membership, the IFI provides opportunities for networking and collaboration, allowing industry stakeholders to share knowledge, develop solutions to common challenges, and advance collective goals.

In addition to the IFI Standards Book, the institute publishes technical guides, manuals, and online resources that keep the industry updated on the latest standards, materials, and technologies. These resources ensure that professionals in the field have access to reliable and authoritative information. By maintaining and distributing this knowledge, the IFI helps standardize practices and improve reliability across the entire fastener supply chain.

The importance of the IFI lies in its ability to ensure that fasteners meet the highest levels of safety, performance, and reliability. This is especially critical in industries such as aerospace, automotive, and infrastructure, where fastener failure could have catastrophic consequences. By providing technical standards, training, advocacy, and collaboration, the IFI creates a common technical language for the fastener industry and fosters trust, consistency, and global competitiveness for its members and the customers they serve.

Industrial Silver Plating

Industrial silver plating is a functional metal finishing process in which a controlled layer of pure silver is deposited onto another metal—such as steel, stainless steel, copper alloys, aluminum, or nickel alloys—to improve conductivity, corrosion resistance, friction behavior, and high-temperature performance. Unlike decorative silver plating, industrial silver plating is engineered for demanding environments and critical components. It is typically applied through electroplating, in which electrical current deposits silver ions from a silver salt solution onto the surface of a part. Many components first receive an underplate—usually nickel or copper—to increase adhesion, prevent diffusion, and ensure long-term stability. Silver thickness is carefully controlled, generally ranging from 5 to 50 microns depending on the electrical, mechanical, or thermal requirements of the application.

Silver plating is used because silver offers the highest electrical conductivity and highest thermal conductivity of any metal, along with excellent reflectivity, corrosion resistance, and high-temperature lubricity. These properties make it indispensable in systems where electrical contact, heat transfer, and mechanical stability must remain reliable over long service lives. Silver remains lubricious up to roughly 650°C, helping prevent galling and seizure, especially in stainless-on-stainless threaded joints. It is also easily soldered or brazed, further improving its utility in assemblies that require dependable joining.

Industrial use of silver plating spans electrical systems, aerospace, fastener technology, cryogenics, HVAC, and precision mechanical assemblies. In electrical and power distribution equipment—such as switchgear, circuit breakers, relays, terminals, connectors, and bus bars—silver plating ensures low contact resistance, reduced heat generation, and stable performance under high loads. In aerospace, turbine systems, and high-temperature assemblies, silver plating provides dry-film lubrication, stable torque-tension behavior, and anti-galling protection for bolts, studs, fasteners, fittings, and engine components exposed to intense heat. In the fastener industry specifically, silver-plated bolts, nuts, studs, and inserts are used in electrical connections, grounding systems, cryogenic applications, and high-temperature environments where galling and torque accuracy are major concerns.

Silver plating is also valuable in cryogenic systems, where silver retains ductility and conductivity at extremely low temperatures, and in brazing, soldering, and joining operations, where silver-plated surfaces improve joint strength and reliability in HVAC, refrigeration, and electronic assemblies. These coatings are usually produced to meet engineering specifications such as ASTM B700, AMS 2410/2411/2412, and the older QQ-S-365, which define thickness levels and quality requirements. Thickness levels typically include 5–10 microns for light electrical needs, 10–25 microns for general engineering use, and 25–50 microns or more for heavy-duty, high-temperature, or high-wear environments.

Ingot

An ingot is a large, solid cast block of metal produced by pouring molten metal into a mold and allowing it to solidify into a convenient shape for handling, storage, transport, and downstream processing. Ingot shapes are designed to be reheated and converted into other mill forms—typically broken down into slabs, blooms, or billets, and then rolled, forged, or extruded into bar, rod, wire, or coil stock that ultimately becomes fasteners and other industrial products.

Ingots are typically made from ferrous metals such as carbon steel, alloy steel, stainless steel, and cast iron, and from nonferrous metals such as aluminum and aluminum alloys, copper and copper alloys (brass/bronze), nickel alloys, titanium alloys, magnesium, and zinc. Producers cast ingots not only for convenience, but also to control and verify chemistry, cleanliness, and internal quality before the metal is worked into the more refined shapes used in manufacturing.

Initial Sample Inspection Report (ISIR)

An Initial Sample Inspection Report (ISIR) is a quality document used to verify and formally document that a supplier’s first production samples (the “initial samples”) conform to the customer’s drawing and specification requirements before routine/series supply begins. It records the inspection and test results performed on those initial samples—typically parts produced under realistic or intended serial production conditions—so the customer can review and approve the part and process for release.

An ISIR is commonly requested in automotive and industrial supply chains and is often associated with VDA Volume 2 (PPF) and/or PPAP submissions; many organizations treat it as the inspection/layout evidence that supports the overall part submission decision (e.g., the warrant/approval package). In German OEM vocabulary it’s frequently tied to “initial sampling” and may be referred to as an Erstmusterprüfbericht (EMPB) conceptually.

For fasteners, an ISIR typically compiles the objective proof that the supplied bolts/screws/nuts/etc. meet requirements, often including dimensional/layout measurements, physical/mechanical properties (and any required lab testing), traceable sample/lot identification, revision status, and documented outcomes (including any noted deviations and their disposition). It is most often issued the first time a specific fastener is supplied to a customer and then re-issued when there are significant product or process changes that require re-approval.

Injection Molding

Injection molding is a manufacturing process used to produce parts by injecting molten material into a mold cavity, where it cools and solidifies into the desired shape. It’s one of the most common and efficient methods for making plastic components, though it can also be used with metals (metal injection molding) and ceramics.

The process begins when plastic pellets (typically thermoplastics like ABS, nylon, or polypropylene) are fed into a heated barrel, where they are melted by both heat and mechanical pressure from a rotating screw. The molten plastic is then injected under high pressure into a precision-engineered steel or aluminum mold, which defines the final shape of the part. Once the material cools and hardens, the mold opens, and the finished part is ejected.

Injection molding allows for high-volume production of complex, detailed, and repeatable parts with minimal post-processing. It’s highly efficient and capable of producing thin-walled components with excellent dimensional accuracy and surface finish.

Common applications include automotive components, medical devices, consumer products, fasteners, electrical housings, and packaging.

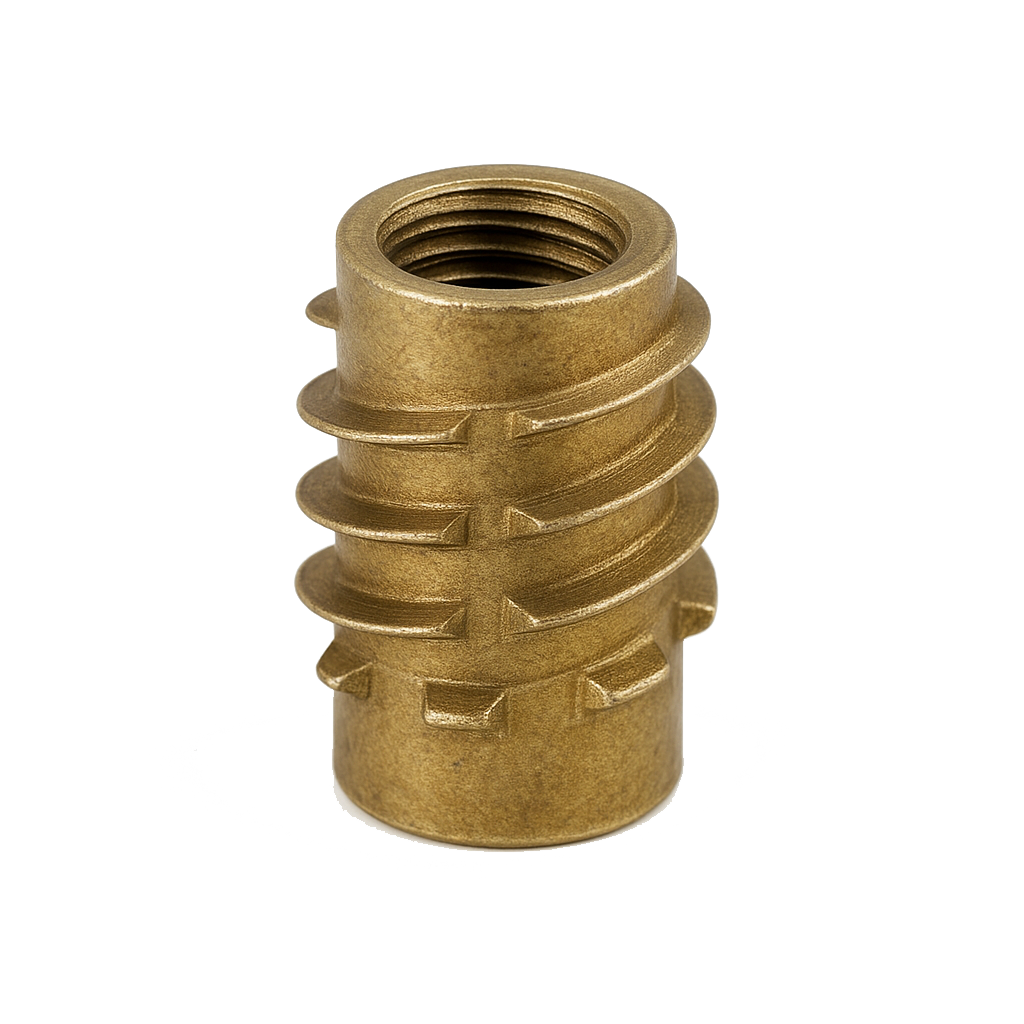

Insert Nut

An insert nut is a fastener used to create a strong, reusable threaded hole in materials that are too soft or thin to hold threads on their own, such as wood, particle board, plastic, or sheet metal. By embedding the insert nut, you avoid stripping or wearing out the base material when bolts or machine screws are repeatedly installed and removed.

They come in different forms depending on the application: coarse-threaded inserts for wood, knurled or ribbed versions for plastics, heat-set inserts that bond into place when the material melts around them, and self-tapping inserts that cut their own threads. You’ll commonly find them in furniture, cabinetry, 3D-printed parts, electronics housings, and other applications where durable, long-lasting threads are required.

Inside Diameter (ID)

Inside diameter (ID) is the diameter of the internal opening of a circular or cylindrical part, measured across the inside surface through the centerline. It describes the “hole size” of components such as tubes, bushings, sleeves, bearings, and washers, and it’s commonly specified along with outside diameter (OD) and length/thickness to fully define a part.

In fastener-related applications, ID is critical because it controls fit and clearance—for example, a washer’s ID must clear the bolt shank, a sleeve’s ID must fit over a pin or fastener, and a bushing’s ID must meet the required running or press-fit relationship with a shaft. For internally threaded parts, the “ID” is often discussed in terms of minor diameter (the smallest diameter at the thread roots), which influences thread engagement, strength, and tap-drill sizing.

Interference Fit Fastener

An interference fit fastener is a type of fastener that relies on a very tight fit—slightly larger than the hole it’s meant to go into—so that it holds in place through friction and compression rather than threads or additional locking features.

In an interference fit (sometimes called a press fit), the fastener’s diameter is intentionally made just a fraction larger than the mating hole. When installed—usually by pressing, hammering, or heating/cooling the parts—the fastener deforms slightly or compresses the surrounding material, creating a secure hold without play. This fit resists loosening from vibration and can be highly durable.

Common in engineering and manufacturing, especially with dowel pins, rivets, bushings, or studs where absolute alignment and zero movement are required. They’re used in aerospace, automotive, and heavy machinery to secure components like gears, bearings, and structural joints where precision and reliability are critical.

Intermetallic Compounds

Intermetallic compounds are solid-state alloys composed of two or more metals that combine in specific, fixed proportions to form a distinct crystalline structure different from that of the pure elements. Unlike ordinary solid solutions (where atoms of one metal dissolve into another), intermetallics have ordered atomic arrangements and defined stoichiometric ratios, such as Ni₃Al (nickel aluminide) or TiAl (titanium aluminide).

These compounds often exhibit unique combinations of properties, including high strength, hardness, and excellent oxidation resistance, even at elevated temperatures. However, they are typically brittle and less ductile than pure metals or standard alloys, which can limit their use in applications requiring significant deformation or impact resistance.

Intermetallic compounds are widely found in nickel-based superalloys, titanium alloys, and aluminum systems, where they act as strengthening phases. For example, Ni₃Al precipitates in nickel-based superalloys provide exceptional high-temperature strength in jet engine components, while TiAl is used in lightweight, heat-resistant parts in aerospace and automotive engineering.

In summary, intermetallic compounds are ordered metallic materials with fixed compositions and strong atomic bonding, offering high mechanical and thermal stability but often at the cost of ductility and toughness. They play a vital role in advanced structural materials, coatings, and high-temperature engineering applications.

Internal Retaining Ring

An internal retaining ring (internal circlip/snap ring) is a spring-steel ring that fits into a groove inside a bore to create a shoulder that prevents components from moving axially out of a housing. It’s the counterpart to an external ring: instead of sitting on a shaft, it seats inside a hole to retain bearings, bushings, seals, or gears.

During installation the ring is compressed, inserted into the bore, and released so it springs into the machined groove. Axial thrust from the retained part is taken by the ring and transferred to the groove wall. Typical materials are carbon spring steel or stainless, with protective finishes such as phosphate, black oxide, or zinc. Rings are sized by bore diameter, and groove width/depth follow standards such as DIN 472 and ASME B18.27 for internal rings.

Common internal styles include the standard circlip with lug holes (installed with snap-ring pliers), spiral (spiral-wound) rings that wind into the groove and provide 360° contact with no lugs, and constant-section (C-rings) with a uniform rectangular cross-section for high load/impact service. (E-style rings exist for bores, but E-rings are more common on shafts.)

Good practice: use the correct pliers/applicator and avoid over-compressing; many stamped circlips have a sharp “punch” edge and a rounded “die” edge—orient the sharp edge toward the primary thrust direction for best retention. Verify groove dimensions and chamfers, and select material/finish to suit the operating environment and load.

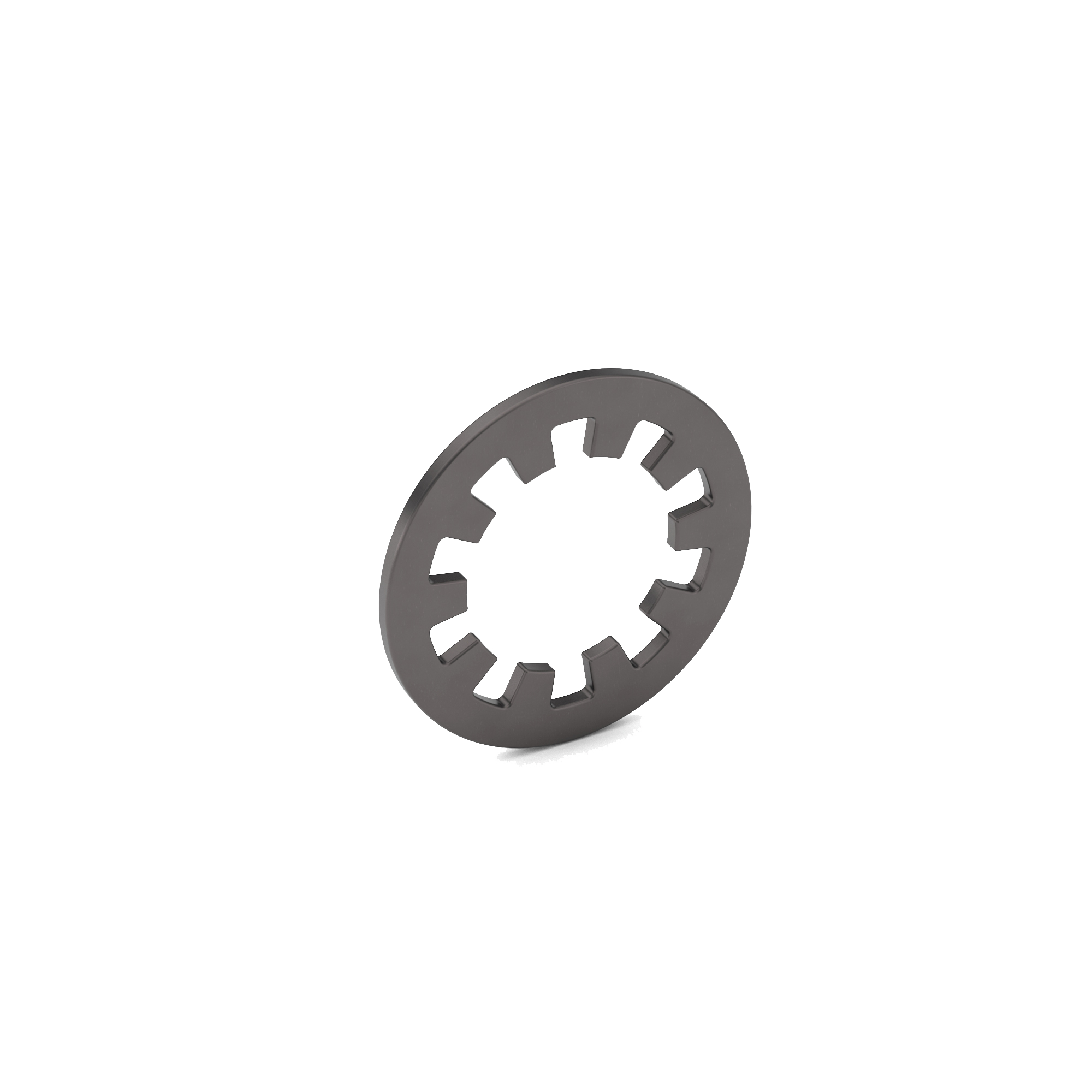

Internal Tab Washer

An internal tab washer is a type of lock washer specifically designed to secure a fastener and prevent it from loosening under vibration, torque, or dynamic loads. Unlike flat washers that primarily spread load, tab washers incorporate protruding tabs that fit into a slot, keyway, or flat surface on a shaft or assembly. These tabs create a positive locking feature, resisting the rotation of the nut or bolt and ensuring stability of the connection.

In terms of design and construction, internal tab washers are typically manufactured as thin, flat rings made from spring steel, stainless steel, or other durable alloys. Their defining feature is the inward-facing tabs along the inner diameter of the washer, which fit into grooves, slots, or keyways on a shaft. Once a fastener is tightened against the washer, the engagement between the tabs and the shaft provides a strong resistance to loosening, keeping the assembly secure.

The main function of an internal tab washer is to act as a locking mechanism that ensures threaded components remain tight under operational stress. By engaging with the shaft, the tabs stop the washer from rotating, while the washer itself provides resistance to the nut or bolt. This combined effect maintains preload in the joint, preventing loss of clamping force, which is essential for safety and reliability in critical assemblies.

Internal tab washers are commonly used in industries where vibration and stress are significant. In automotive and aerospace applications, they are found in gearboxes, engines, and rotating machinery. In industrial equipment, they are widely applied in pumps, turbines, and heavy machinery. They are also used in electrical and mechanical assemblies where cyclic loading could otherwise cause bolts and nuts to loosen.

The advantages of internal tab washers include providing a positive mechanical locking method without the need for adhesives or secondary devices. They are simple, effective, and compact, often reusable depending on the material and design. Their small footprint makes them particularly useful in confined assemblies where space is limited.

However, they also have limitations. Internal tab washers must be matched precisely to the shaft size and slot or groove design, and they are less effective on smooth shafts without keyways. Under extreme loads, the tabs may wear down or shear off, reducing their effectiveness. Additionally, proper installation and alignment are crucial, as the washer’s locking function depends on the tabs fully engaging with the shaft.

Internal Thread

A helical groove cut inside a hole that allows a bolt or screw with matching external threads to be fastened securely. Internal threads are commonly found in nuts, tapped holes, and other threaded components

Internal Tooth Lock Washer

An Internal Tooth Lockwasher is a type of lock washer designed with teeth or serrations located on the inner edge of the washer. These teeth bite into the surface of the fastener or material being secured when the fastener is tightened, creating additional friction and resistance to prevent loosening due to vibration, rotation, or thermal expansion.

Internally Threaded Inserts

Internally threaded inserts are cylindrical fasteners that are installed into a material to provide a durable, reusable female thread (internal thread) for fastening bolts or screws. They allow you to install a strong internal thread in materials that are too soft, thin, or prone to wear—such as plastic, wood, aluminum, or composite.

Iron (Fe)

Iron is a metallic element with the chemical symbol Fe (from the Latin ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is one of the most abundant elements on Earth—making up about 5% of the Earth's crust—and is the primary component of the planet’s core. Iron is the foundation of modern industry and metallurgy, serving as the base metal for steel, which is the most widely used material in the world.

In its pure form, iron is a lustrous, silvery-gray metal that is relatively soft and ductile. However, pure iron is rarely used in practice because it corrodes easily when exposed to moisture and oxygen, forming iron oxide (rust). Instead, iron is almost always used in alloy form, where it’s combined with small amounts of other elements such as carbon, chromium, nickel, or molybdenum to improve its strength, hardness, and corrosion resistance.

Iron’s versatility comes from its ability to exist in several crystalline forms (allotropes) and to combine easily with other elements. When carbon is added in controlled amounts (typically 0.02–2.1%), it becomes steel, which can be hardened, tempered, and alloyed for countless industrial applications. Higher carbon content (above 2%) produces cast iron, which is harder but more brittle.

Most of the world’s iron is extracted from iron ore, primarily from minerals like hematite (Fe₂O₃) and magnetite (Fe₃O₄). The extraction process involves smelting, where the ore is heated in a blast furnace with coke (carbon) and limestone. This chemical reduction removes oxygen from the ore, producing molten pig iron, which is then refined into steel or other iron-based alloys.

Iron’s unique combination of strength, magnetism, and abundance makes it indispensable across nearly every industry. It’s used in construction (beams, rebar, bridges, ships), machinery, automobiles, tools, pipelines, and fasteners. It also plays a vital biological role—iron atoms in hemoglobin enable red blood cells to carry oxygen throughout the body.

Iron Ore

Iron ore is a naturally occurring mineral rock from which metallic iron (Fe) can be economically extracted. It serves as the primary raw material for producing iron and steel, which together make up about 95% of all metal used globally. The ore itself is a combination of iron-bearing minerals and impurities such as silica, alumina, and other oxides.

To extract usable iron, the ore must contain a high percentage of iron compounds, typically iron oxides, which can be reduced to pure metallic iron through smelting in a blast furnace or a direct reduction process. The most important iron-bearing minerals are:

- Hematite (Fe₂O₃): Usually red to reddish-brown in color and containing up to 70% iron, hematite is one of the richest and most sought-after iron ores. It is the principal source of iron in many modern steelmaking operations.

- Magnetite (Fe₃O₄): A black, magnetic mineral containing about 72% iron, magnetite is the highest-grade iron ore. It often requires magnetic separation to concentrate the iron before smelting.

- Goethite (FeO(OH)) and Limonite (FeO(OH)·nH₂O): Brownish ores with lower iron content (40–60%) that often form through weathering of other iron minerals.

- Siderite (FeCO₃): An iron carbonate mineral containing around 48% iron, used less commonly because it requires additional processing to remove carbon dioxide.

The process of turning iron ore into usable metal begins with mining, followed by crushing, grinding, and concentration to increase the iron content and remove impurities. The resulting iron ore concentrate or pellets are then fed into a blast furnace, where they are chemically reduced by carbon monoxide (produced from coke) according to reactions such as:

Fe2O3+3CO→2Fe+3CO2

This reduction converts iron oxide into molten pig iron, which can then be refined into steel or cast iron.

Major iron ore deposits are found in Australia, Brazil, China, India, Russia, and the United States, with Australia and Brazil accounting for the majority of global exports. The ore is typically transported as raw rock, concentrate, or pellets to steel mills around the world.

Iron Oxide

Iron oxide is a compound formed when iron (Fe) reacts with oxygen (O₂), creating a family of chemical compounds that consist of iron and oxygen in various ratios. These compounds occur naturally as minerals and artificially through corrosion, oxidation, or controlled synthesis, and they are among the most common inorganic materials on Earth.

Chemically, iron oxides are represented by several forms, depending on the oxidation state of iron and the environment in which they form. The three most significant types are:

1. Iron(II) oxide (FeO) — also known as wüstite, this is a black or dark gray compound where iron is in the +2 oxidation state. It typically forms under low-oxygen conditions or as an intermediate product in high-temperature reactions such as steelmaking. FeO is unstable in air and tends to oxidize further.

2. Iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃) — commonly called hematite or rust, this is a reddish-brown compound in which iron is in the +3 oxidation state. It is the most stable and widespread form of iron oxide, found both in nature (as hematite ore) and as the end product of corrosion when iron or steel reacts with oxygen and moisture. The reaction can be summarized as:

4Fe + 3O₂ → 2Fe₂O₃

3. Iron(II,III) oxide (Fe₃O₄) — also known as magnetite, this compound contains both Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ ions and has a black, magnetic appearance. It forms under moderate oxygen conditions and is used in magnets, pigments, and recording materials. The oxidation process can be written as:

3Fe + 2O₂ → Fe₃O₄

These oxides are not only important in geology and metallurgy but also have widespread industrial and technological uses. For instance, iron oxides serve as pigments (red, yellow, and black iron oxides) in paints, ceramics, and cosmetics; as polishing agents (jeweler’s rouge); and as magnetic materials in electronics and data storage.

In corrosion, iron oxides are often undesirable, forming the flaky, porous “rust” that compromises structural integrity. However, controlled oxidation is sometimes beneficial—such as in passivation layers on stainless steel, where a stable oxide film protects against further corrosion.

ISO (International Organization for Standardization)

ISO is the International Organization for Standardization, a global, non-governmental body founded in 1947 and based in Geneva, Switzerland. It develops and publishes international standards to ensure quality, safety, efficiency, and worldwide compatibility across industries.

In the fastener industry, ISO standards specify dimensions, tolerances, material grades, finishes, and mechanical properties of bolts, nuts, washers, and screws. They often replace or harmonize older national standards such as DIN (Germany), BS (Britain), and ANSI/ASTM (United States), making fasteners interchangeable globally. For example, ISO 4017 defines requirements for a fully threaded hexagon head bolt, replacing DIN 933. Because ISO standards are recognized worldwide, they allow fasteners manufactured in one country to fit with components or tools from another, ensuring consistency in industries like aerospace, automotive, construction, and machinery.

In short, ISO guarantees that an ISO-designated fastener will meet the same specification anywhere in the world.