Resources

Glossary

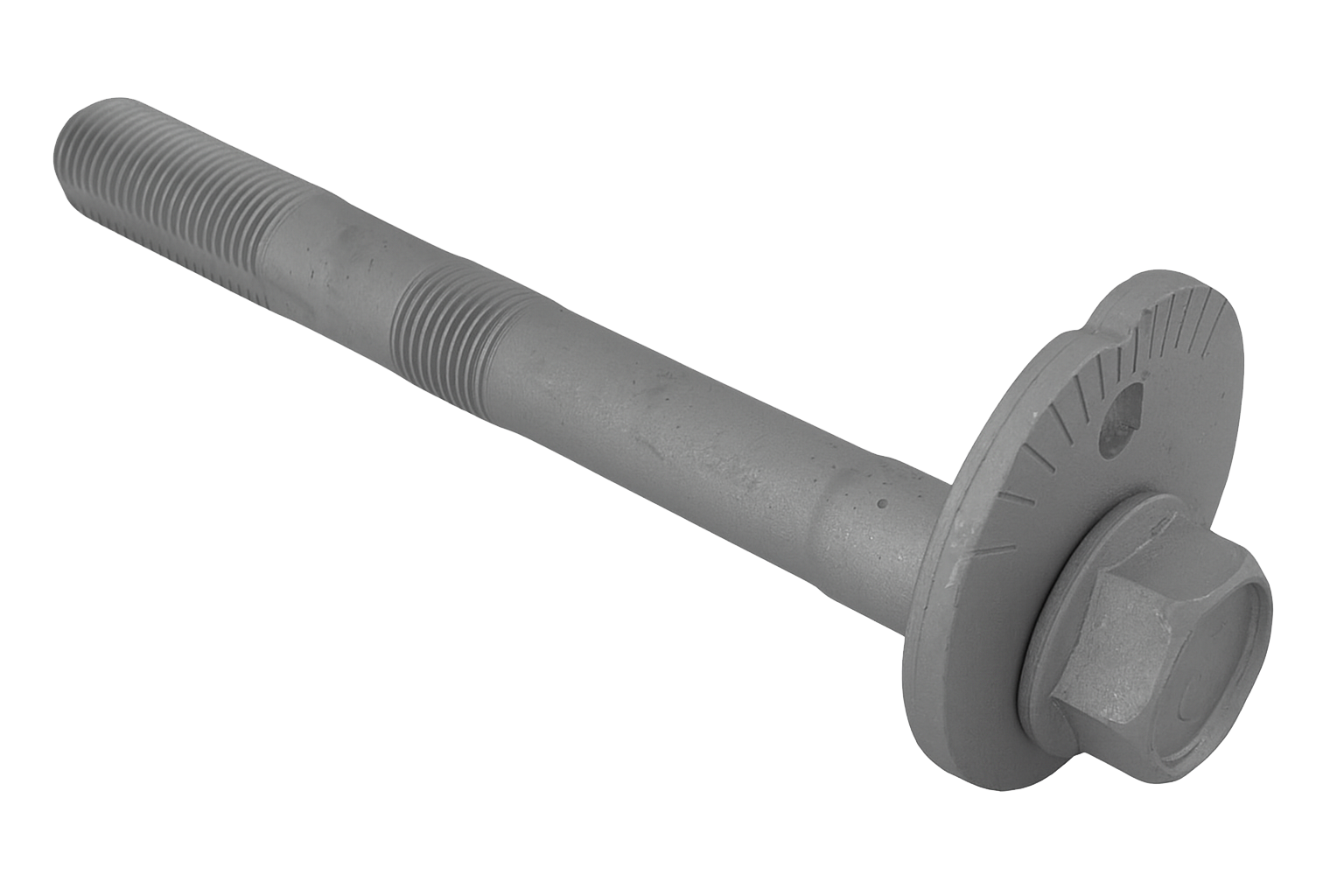

Eccentric Bolt

An eccentric bolt is a specialized fastener designed with the bolt’s shaft or shank offset (eccentric) from its centerline relative to the head or cam surface. This intentional offset allows the bolt to function not only as a fastening element but also as a precision adjustment mechanism—most commonly for alignment, tensioning, or camber correction in mechanical assemblies.

In a standard bolt, the shank runs concentrically through the center of the head, meaning it rotates without changing the position of the attached part. In contrast, an eccentric bolt has a cam-shaped or offset head and shank, so when it is rotated, the bolt’s position changes relative to the mounting hole. This motion provides fine adjustment of position, angle, or spacing between components without the need for additional tools or spacers.

Eccentric bolts are widely used in automotive suspension systems, particularly for camber and caster adjustments in control arms, strut mounts, and subframes. When the bolt is turned, the eccentric head or washer shifts the component slightly, altering the wheel’s alignment angle. Once the desired position is set, the bolt is tightened to lock the assembly in place.

In industrial and mechanical engineering, eccentric bolts appear in conveyor systems, machine mounts, precision fixtures, and tensioning devices—anywhere controlled movement or calibration is needed. They are often used alongside eccentric washers or cams, which provide a larger contact surface for smooth adjustment.

Eccentric bolts are typically made from hardened alloy steel or stainless steel to withstand repetitive movement and vibration. Many are zinc-plated, phosphate-coated, or black oxide finished for corrosion resistance. The design may vary—some have a built-in eccentric cam under the head, while others use eccentric washers that rotate independently around a standard bolt shank.

Eccentric Locknut

An eccentric locknut is a type of locknut designed with an off-center (eccentric) collar or ring that creates a wedging action when tightened onto a bolt or threaded stud. Unlike a standard nut, the eccentric feature causes the threads of the nut to press tightly against the bolt’s threads, generating friction that resists loosening from vibration or dynamic loads.

The locking action does not rely on additional components like washers or adhesives—it’s built directly into the nut’s geometry. Once installed, the eccentric section of the nut slightly distorts the thread fit, increasing resistance to rotation. This makes it reusable and reliable in high-vibration environments.

Where you’ll see them

Automotive and heavy machinery where vibration is constant.

Railway and aerospace applications where safety and security are critical.

Industrial equipment where repeated maintenance and reassembly occur, since the nut maintains its locking ability over multiple uses.

Eccentric Pin

An eccentric pin is a mechanical component with an offset cylindrical axis, meaning the center of its shaft is intentionally not aligned with the center of its head or mounting surface. This eccentricity allows the pin to convert rotary motion into linear motion or to adjust alignment and position in precision assemblies.

In design, an eccentric pin typically consists of a cylindrical body with a concentric head or flange and a shaft whose axis is offset from the head’s axis by a small, controlled amount. When the pin is rotated, the offset causes the attached component—such as a cam follower, roller, or guide block—to move slightly side to side or up and down, depending on the configuration.

Eccentric pins are used extensively in mechanical linkages, cam mechanisms, jigs, fixtures, and tooling assemblies where precise micro-adjustments are needed. They are common in die and mold alignment, robotics, machine tools, and automotive assemblies, where engineers can fine-tune fit or alignment simply by rotating the pin rather than machining new parts.

They are usually made from hardened steel, stainless steel, or alloy steel, ensuring durability and resistance to wear under repeated motion or load. In some cases, they are paired with locking screws or nuts to maintain the adjusted position once set.

Eddy Current Testing (ECT)

Eddy Current Testing (ECT) is a non-destructive testing (NDT) method that relies on electromagnetic induction to detect flaws in conductive materials. A probe containing a coil is energized with alternating current, which generates a changing magnetic field. When the probe is brought near a conductive material, this field induces circulating electrical currents—called eddy currents—at the surface. These eddy currents in turn produce their own opposing magnetic fields, which alter the electrical impedance of the probe’s coil. If the material is free from defects, the eddy currents flow in a predictable way. However, when there is a discontinuity such as a crack, corrosion pit, or thinning of the material, the flow of eddy currents is disrupted, and the resulting change in coil response is measured and displayed on an instrument.

ECT is widely used in aerospace, power generation, and manufacturing industries for detecting cracks in aircraft skins, measuring tube wall thickness in heat exchangers, inspecting welds, and monitoring corrosion under paint or thin coatings. It has several advantages: it is fast, highly sensitive to small surface-breaking flaws, requires little or no surface preparation, and can even detect defects through thin coatings. Unlike ultrasonic testing, it does not require couplants, and unlike radiographic testing, it does not involve radiation. However, it does have limitations: it only works on electrically conductive materials, its penetration depth is shallow (best for surface and near-surface defects), and accurate interpretation depends heavily on the skill of the operator and proper calibration with reference standards. Despite these constraints, ECT remains an essential inspection method wherever precision, speed, and sensitivity are required.

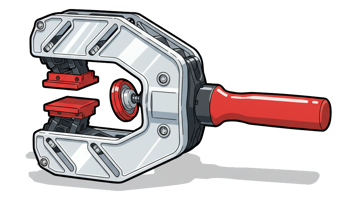

Edge Clamp

An edge clamp is a mechanical holding device designed to secure a workpiece by applying clamping force from the side (edge) rather than from above, as in traditional clamps. This makes it especially useful in machining, woodworking, welding, and assembly operations where the top surface of the workpiece must remain unobstructed for milling, drilling, measuring, or gluing.

Structurally, an edge clamp typically consists of a body or base that mounts to a table, fixture plate, or T-slot, along with a cam, wedge, or screw mechanism that drives a jaw or pad sideways into the edge of the material. Some designs also include a secondary downward component that applies a dual-action force—pressing the workpiece both horizontally and vertically to hold it securely against the table surface.

Edge clamps are commonly made from hardened steel, aluminum, or cast iron for strength and stability. They come in many configurations, including manual screw clamps, cam-action clamps, pneumatic or hydraulic edge clamps, and modular fixture clamps used in CNC machining setups.

These clamps are widely used in metalworking, woodworking, and manufacturing. In machining, they hold flat plates or parts for milling or drilling without interfering with tool paths. In woodworking and cabinetmaking, edge clamps are often used to join boards or apply pressure along edges during gluing. In welding and fabrication, they align and secure plates or structural members for precise joining.

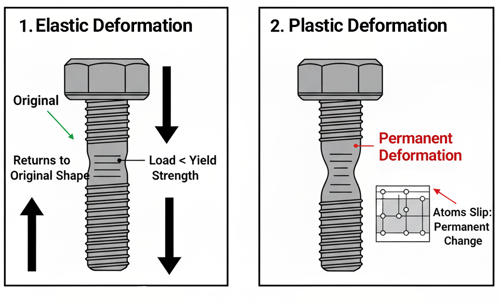

Elastic Deformation

Elastic deformation is the temporary change in shape or size of a material that occurs when an external force or stress is applied, but the material returns to its original shape once the force is removed. It happens within the material’s elastic limit, meaning the internal atomic bonds are stretched or compressed but not permanently rearranged. The relationship between stress and strain in this region follows Hooke’s Law, which states that the deformation is directly proportional to the applied load.

In simpler terms, when a force is applied to a bolt, spring, or metal rod, it may elongate or compress slightly, but once the load is removed, it returns to its initial length and form. This behavior occurs because the atomic structure of the material only experiences reversible displacements—the bonds between atoms act like tiny springs that stretch and recover.

Elastic deformation is a critical concept in engineering and materials science because it defines the safe working range of a material. Designers and engineers ensure that fasteners, beams, and machine components operate below their elastic limit to prevent permanent deformation or failure. When the stress exceeds this limit, the material enters the plastic deformation stage, where changes become irreversible.

In summary, elastic deformation is a reversible, proportional response to stress, allowing materials to absorb energy and return to their original form once the load is released. It represents the phase before permanent, plastic deformation begins.

Elastic Limit

The elastic limit is the maximum stress a material can withstand and still return to its original shape once the load is removed. Below this point, deformation is fully elastic—atoms in the material’s crystal lattice are displaced slightly but return to their original positions when the stress is released. If the stress goes beyond the elastic limit, the material enters plastic deformation, where the changes in shape are permanent and the material will not fully recover its original dimensions.

The elastic limit is closely related to, but not always identical to, the yield strength, which marks the onset of measurable permanent deformation. It is a critical property in the design of fasteners, springs, and structural components, because keeping stresses within the elastic range ensures a part can repeatedly bear loads without lasting damage. Exceeding the elastic limit can cause permanent distortion or failure, especially in applications where tight tolerances, fatigue resistance, or safety are essential.

Elastic Stop Nut

An elastic stop nut (often called a nyloc nut or nylon insert locknut) is a type of locknut that incorporates a non-metallic insert, usually made of nylon, at the top of the nut. When the nut is tightened onto a bolt or threaded stud, the threads of the bolt cut into the nylon insert, creating friction and resistance that prevents the nut from loosening due to vibration or dynamic loads.

Unlike ordinary nuts that may back off under vibration, the elastic insert keeps constant pressure on the threads. This locking feature does not damage the bolt threads and allows the nut to be reused several times, though the locking ability decreases after repeated installations.

Elastic stop nuts are widely used in aerospace, automotive, machinery, and industrial applications where vibration resistance is critical. They are especially common in assemblies that experience continuous motion or dynamic stress, such as engines, airframes, and equipment frames.

Elastomer Coating

Elastomer coating is a flexible, rubber-like protective layer made from polymeric materials known as elastomers, which can stretch and return to their original shape without cracking or losing adhesion. These coatings are applied to surfaces to provide durability, weather resistance, chemical protection, and waterproofing, while also allowing for expansion and contraction of the underlying material.

Elastomers are polymers with elastic properties, meaning they can elongate significantly and recover their shape when stress is removed. Common elastomeric materials used in coatings include polyurethane, silicone, acrylic, butyl, neoprene, and EPDM (ethylene propylene diene monomer). When formulated as coatings, they combine elasticity with strong adhesion and resistance to UV radiation, moisture, and temperature extremes.

Elastomer coatings are widely used in construction, automotive, marine, industrial, and electrical applications. In the building industry, they are often applied to roofs, walls, and concrete structures as seamless waterproof membranes that can bridge small cracks and protect against leaks, corrosion, and UV damage. In industrial environments, elastomer coatings are used to line tanks, pipes, machinery, and fasteners to resist abrasion, vibration, and chemical attack. In automotive and aerospace settings, they serve as protective or noise-dampening coatings, often applied to components exposed to harsh weather or mechanical stress.

The defining advantage of elastomer coatings is their ability to flex and move with the substrate. Unlike rigid coatings (such as epoxy or enamel), elastomer coatings do not crack under thermal expansion, vibration, or impact. They also provide excellent adhesion, sealing, and corrosion resistance, making them suitable for both metal and nonmetal substrates like concrete, rubber, and composites.

Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM)

Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM) is a non-traditional machining process that removes material from a conductive workpiece using controlled electrical discharges, or sparks. Instead of relying on physical contact to cut, EDM erodes the material by creating rapid, repetitive sparks between an electrode and the workpiece, both of which are submerged in a dielectric fluid. This makes EDM uniquely capable of machining extremely hard materials and producing complex, precise shapes that conventional machining methods cannot easily achieve.

The process works by placing a tool electrode, often made of graphite, copper, or brass, into a dielectric fluid along with the conductive workpiece. A voltage is applied between them, and as they are brought close, a spark discharge jumps across the gap. This discharge generates intense localized heat—ranging from 8,000 to 12,000 °C—that melts and vaporizes a tiny portion of the workpiece. The dielectric fluid cools the area, flushes away debris, and prevents continuous arcing. Because the spark frequency, duration, and position can be carefully controlled, EDM is able to achieve high precision in material removal.

There are several main types of EDM. Die-Sinking EDM (or Ram EDM) uses a shaped electrode that is pressed into the workpiece to create a cavity of the same form, which is commonly used for molds and dies. Wire EDM relies on a thin, continuously fed brass wire electrode to cut through a workpiece in a manner similar to a bandsaw, producing fine and accurate cuts. Hole Drilling EDM is specialized for making very small, deep holes by using tubular electrodes.

The applications of EDM are widespread. In tool and die making, it is invaluable for producing molds, dies, and punches with intricate details. In the aerospace and automotive industries, EDM is used to machine hard alloys, turbine blades, and engine components. The medical field employs EDM to create precise parts from biocompatible metals like titanium. It is also essential in micro-machining, where it produces tiny, complex parts for electronics. Additionally, EDM is well-suited for shaping very hard materials such as carbide, hardened steel, and exotic alloys.

EDM offers several advantages. It can machine very hard and brittle materials that are otherwise difficult to process. It allows the creation of complex shapes and fine details with high precision. Because there is no direct contact between the tool and the workpiece, there are no cutting forces, making it ideal for delicate or thin features that could distort under stress.

However, EDM also has limitations. It only works on electrically conductive materials, so non-conductive materials cannot be machined with this method. It is slower than conventional machining when removing large amounts of material. Electrodes wear down over time and must be replaced, adding to costs. Finally, depending on the application, the surface finish may require additional post-processing to meet requirements.

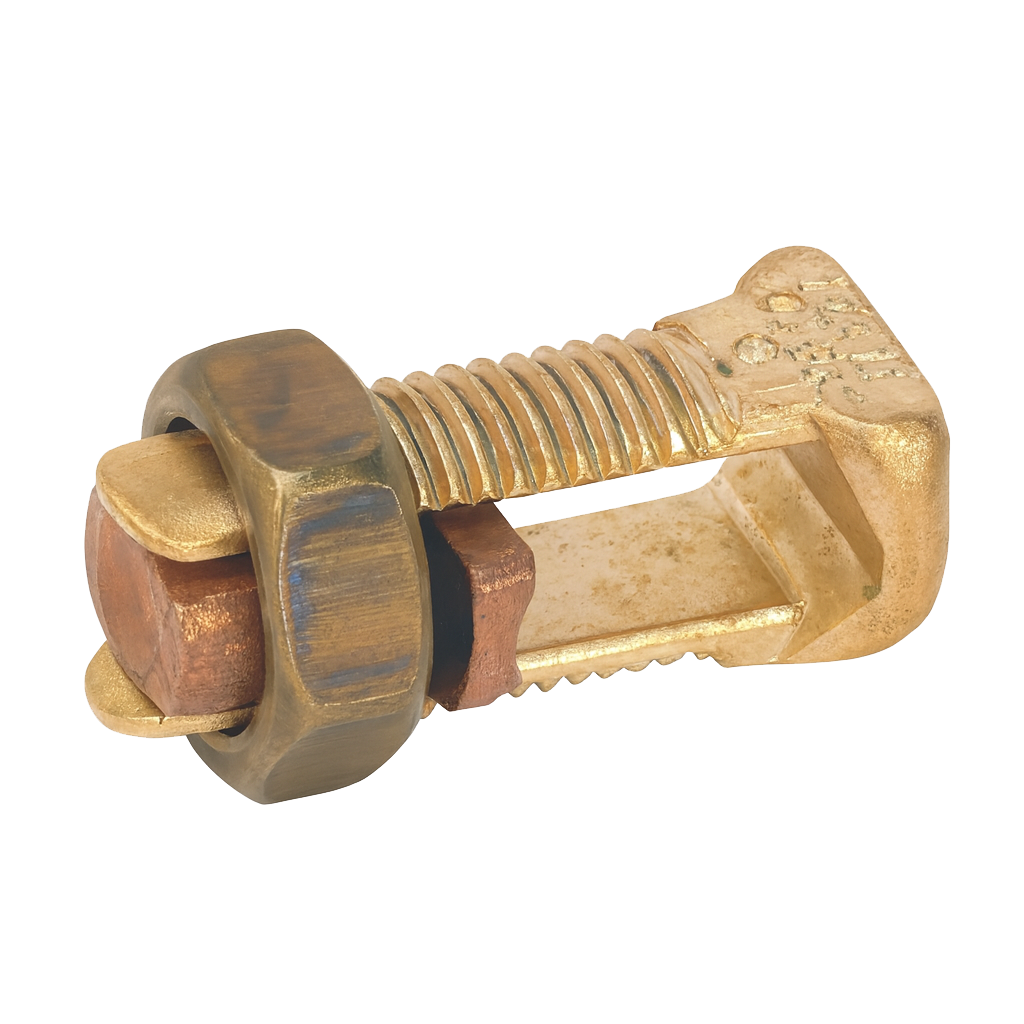

Electrical Earth Bolt

An electrical earth bolt (also called a grounding bolt or earthing stud) is a specialized fastener used to create a secure electrical connection between equipment and the earth (ground) for safety and conductivity. It ensures that any stray electrical current or fault voltage is safely directed into the ground, preventing electric shock, equipment damage, or fire.

An earth bolt is typically installed on metal enclosures, machinery frames, panels, or electrical housings, providing a central grounding point. The bolt is usually made from high-conductivity metals such as brass, copper, or tinned steel, which allow efficient current transfer and resist corrosion. It may include lock washers, flat washers, and nuts to maintain a tight, vibration-resistant connection over time.

Structurally, an earth bolt looks like a regular hex bolt but often includes a pre-attached grounding lug or multiple terminals to connect several grounding wires. It may also have markings or color coding (often green or yellow-green) to identify it as part of the grounding system. In electrical cabinets, switchgear, or automotive applications, the bolt connects to the system’s grounding cable or chassis to ensure all metal parts remain at the same electrical potential.

Earth bolts are governed by standards such as IEC 60999, BS 951, or UL grounding requirements, depending on the region. Proper installation involves cleaning any paint or coating off the contact surface to ensure bare metal-to-metal contact, tightening to the correct torque, and sometimes applying anti-corrosion compound to maintain conductivity over the long term.

AKA: Grounding Bolt, Earthing Stud

Electrochemical Corrosion

Electrochemical corrosion is a type of metallic corrosion that occurs when a metal deteriorates through an electrochemical reaction involving anodic oxidation and cathodic reduction—essentially forming a tiny battery or galvanic cell on the metal’s surface. This process takes place when a metal, an electrolyte (like water with dissolved salts), and oxygen or another oxidizing agent are all present, allowing electrical current to flow between different areas of the metal.

In simple terms, corrosion happens because metals naturally want to return to their more stable, oxidized state, just like they exist in nature as ores. The electrochemical process allows this to occur through a redox reaction, where one area of the metal loses electrons (oxidation) and another gains them (reduction).

Here’s how it works:

1. Anodic reaction (oxidation):

At certain microscopic sites on the metal surface—called anodic regions—metal atoms lose electrons and dissolve into the surrounding electrolyte as metal ions. For example, in the case of iron:

Fe → Fe²⁺ + 2e⁻

This is where corrosion (metal loss) physically occurs.

2. Cathodic reaction (reduction):

The released electrons flow through the metal to another region—the cathode—where they are consumed by a reduction reaction, usually involving oxygen and water. In a neutral or basic environment, this is typically:

O₂ + 2H₂O + 4e⁻ → 4OH⁻

3. Electrolyte conduction:

The electrolyte (such as rainwater, seawater, or moisture on the surface) allows ionic movement between the anodic and cathodic areas, completing the electrochemical circuit.

4. Corrosion product formation:

The metal ions produced at the anode often react with oxygen or hydroxide ions in the electrolyte to form corrosion products—for example, iron oxide (rust) in steel.

Over time, this continuous cycle of oxidation and reduction leads to the gradual degradation of the metal. The process can be localized (as in pitting or crevice corrosion) or uniform, depending on environmental conditions, surface composition, and the presence of impurities or protective coatings.

Electrochemical corrosion is influenced by several factors, including:

- Electrochemical potential differences between microstructures or different metals.

- Electrolyte conductivity (higher salt content accelerates corrosion).

- Temperature and pH of the environment.

- Oxygen availability, which controls the cathodic reaction rate.

A classic example is galvanic corrosion, where two dissimilar metals (e.g., steel and copper) are electrically connected in a conductive environment. The more active metal (anode) corrodes faster, while the more noble metal (cathode) is protected.

To prevent electrochemical corrosion, engineers use methods such as protective coatings (paint, plating, galvanizing), cathodic protection (sacrificial anodes or impressed current systems), corrosion inhibitors, and material selection based on galvanic compatibility.

Electroless Nickel Plating

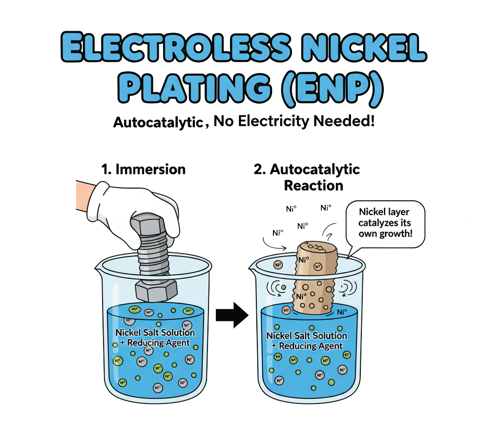

Electroless nickel plating (ENP) is a chemical plating process that deposits a uniform layer of nickel-phosphorus or nickel-boron alloy onto a substrate without the use of an external electrical current. Unlike traditional electroplating, which relies on electric current to drive metal deposition, electroless nickel plating uses an autocatalytic chemical reaction—meaning the metal itself helps catalyze its own deposition.

The process begins by immersing the part in a nickel salt solution (usually nickel sulfate or nickel chloride) along with a reducing agent, most commonly sodium hypophosphite. The reducing agent chemically reduces nickel ions (Ni²⁺) to metallic nickel (Ni⁰), which deposits evenly on the surface. Once the first layer of nickel forms, it becomes catalytic, allowing the reaction to continue and build up the coating uniformly.

This method offers a major advantage: the coating thickness is completely uniform, even on complex geometries, recesses, threads, and internal surfaces—areas that are often unevenly coated during electroplating. This makes ENP ideal for precision parts, valves, pumps, fasteners, and molds where tight tolerances and smooth finishes are required.

Electroless nickel coatings can be tailored to specific applications based on their phosphorus content:

- Low-phosphorus (2–5%) coatings are hard, wear-resistant, and conductive.

- Medium-phosphorus (6–9%) coatings provide a balance of hardness and corrosion resistance.

- High-phosphorus (10–13%) coatings offer excellent corrosion and chemical resistance, making them ideal for marine or chemical environments.

After plating, the coating can be heat-treated to increase hardness—up to 1,000 HV (about 70 Rockwell C)—comparable to hardened steel. It also improves adhesion and wear resistance.

Electroless nickel plating is widely used across aerospace, automotive, oil and gas, electronics, and tooling industries. Common applications include gear components, hydraulic pistons, molds, connectors, and shafts. Its combination of hardness, smoothness, lubricity, and corrosion protection makes it one of the most versatile surface treatments available.

Electrophoretic Coating (E-Coat)

An electrically applied finish used to add corrosion protection to large or complex parts such as truck frames, food and beverage containers, tractors, and other industrial equipment. Sometimes referred to as a coating, this process is more similar to electroplating. Parts are dipped into a tank filled with a water-based solution containing coating materials. An electric current is then applied, causing particles to bond evenly to the submerged surface. After application, parts are typically cured in an oven through a process called cross-linking, which helps bond the coating to the base material.

Appearance - The defining characteristic of an E-Coat is its exceptionally uniform and consistent appearance. Thanks to the electrical application process, the coating thoroughly covers all surfaces, including complex geometries and internal areas, without the risk of runs, drips, or sags.

Electroplating (Plating)

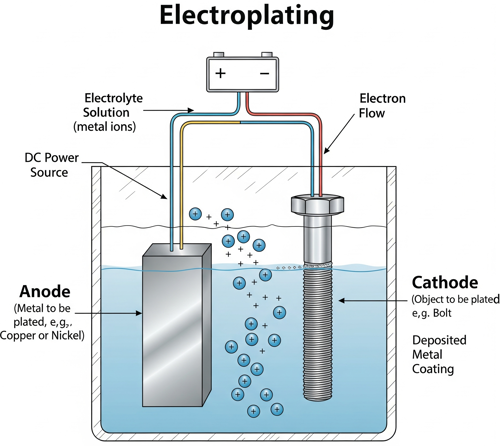

Electroplating is a metal finishing process that uses electric current to deposit a thin layer of metal onto the surface of another material—usually metal, but sometimes plastic or other conductive substrates. The main goals of electroplating are to improve corrosion resistance, enhance appearance, reduce friction, increase hardness, or provide electrical conductivity.

The process works through electrochemical deposition. The part to be plated (called the cathode) is submerged in a solution containing dissolved metal ions from the plating material, while another piece of the plating metal (the anode) is also immersed in the same solution. When direct current (DC) is applied, metal ions in the solution are attracted to and deposit onto the cathode, forming a uniform, tightly bonded metal coating.

For example, in zinc electroplating, a steel bolt is placed in a solution of zinc sulfate. When electricity flows, zinc ions are reduced and bond to the steel surface, forming a corrosion-resistant zinc coating.

The thickness and quality of the electroplated layer can be controlled by adjusting factors such as current density, plating time, temperature, and solution composition. The resulting finish can range from bright and decorative (like chrome or nickel) to functional and protective (like zinc, copper, or tin).

Common metals used in electroplating include:

- Zinc – for corrosion protection on steel.

- Nickel – for hardness and a smooth, bright finish.

- Chromium – for durability, luster, and wear resistance.

- Copper – for electrical conductivity and as an underlayer in multi-metal coatings.

- Gold and silver – for conductivity, aesthetics, and corrosion resistance in electronics.

AKA: Electro-Galvanizing

Electropolishing

Electropolishing is an electrochemical finishing process used to smooth, polish, and clean the surface of metal parts. Instead of removing material by mechanical grinding or sanding, it uses an electrical current in combination with a chemical electrolyte to dissolve a very thin layer of the metal’s surface. This process levels out microscopic peaks, reduces surface roughness, and leaves behind a bright, reflective, and clean finish.

During electropolishing, the metal part is connected as the positively charged anode and immersed in a specially formulated acid bath. A cathode (negatively charged electrode) is also placed in the solution. When electrical current passes through, the microscopic high points on the surface dissolve faster than the low points. As a result, the surface becomes smoother and more uniform at the microscopic level.

Electropolishing provides several advantages: it improves corrosion resistance by removing surface contaminants and embedded particles, reduces the risk of stress corrosion cracking, makes surfaces easier to clean, and enhances the appearance of the part with a shiny finish. It is often used for stainless steel, titanium, aluminum, and other metals in industries such as medical device manufacturing, food processing, aerospace, and pharmaceuticals—where extremely clean, smooth, and passivated surfaces are critical.

Embedment Relaxation

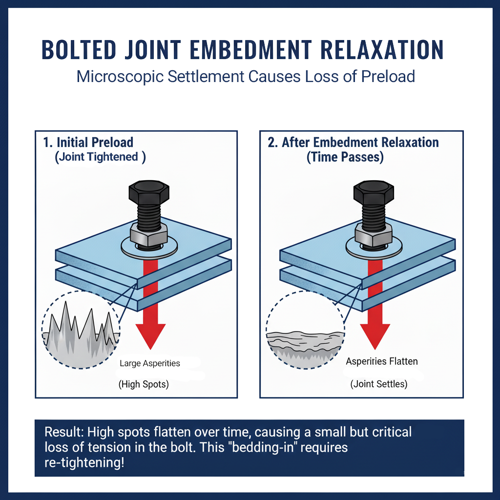

Embedment relaxation (also called bedding-in or joint settlement) is the early loss of clamp load in a bolted joint that occurs as microscopic surface high spots—asperities—flatten under preload; after tightening, the nut/washer bearing surfaces and the thread flanks contact only at scattered peaks, and as those peaks plastically flow, coatings or paint cold-flow, and burrs seat, the joint stack becomes slightly thinner, which shortens the bolt and reduces its tensile preload, and this drop can be approximated with the inline relation “the clamp-force loss is ΔF ≈ k_bolt·Δδ_embed,” where k_bolt is the bolt’s axial stiffness and Δδ_embed is the amount of settlement. It is largely a one-time effect that unfolds over minutes to hours (or a few early load cycles) and is distinct from stress relaxation/creep (time-dependent loss at elevated temperature) and from self-loosening (rotation under vibration), though all three can interact.

The magnitude is small in thickness but meaningful in force: for a typical M12 class 10.9 bolt with k_bolt ≈ 80 kN/mm, a settlement of about 0.05 mm produces roughly 4 kN of preload loss—often a few percent up to ~10% of initial preload in steel-on-steel joints, and potentially higher with soft materials like aluminum or plastics, rough finishes, squishy coatings/paint, burrs, or multiple interfaces. Most settlement occurs under the nut or bolt head/washer (bearing surface seating and coating compression), at the thread flanks (asperity flattening and micro-yield), and between the joined parts if surfaces are rough, non-parallel, or include gaskets or shims. This matters because lower clamp load increases the risk of joint slip, micro-movement, fretting, and vibratory loosening, and it also skews torque-to-tension expectations during rework.

You can reduce embedment relaxation by controlling contact surfaces (machine or grind bearing faces, deburr, avoid thick soft paint where parts seat, and use hardened flat washers), choosing finishes and coatings that stabilize friction without excessive compressible thickness (e.g., phosphate-and-oil, MoS₂, PTFE, zinc-flake systems), and using a tightening strategy that accommodates seating (for example, a snug-pause-final sequence or torque-angle/torque-to-yield methods for better tension control, with a targeted retorque after initial seating to recover preload). Design choices that raise joint stiffness relative to bolt stiffness—shorter grip length, larger under-head bearing area, stiffer clamped members—also help, and verification tools such as load-indicating washers (DTIs), direct-tension bolts, or ultrasonic elongation confirm that the final clamp load remains after bedding-in. Lubrication won’t eliminate embedment itself, but consistent lubrication trims friction scatter so the achieved preload is closer to target despite the inevitable settlement.

AKA: Bedding-In, Joint Settlement

Enclosed Nut

An enclosed nut—also commonly called a cap nut or acorn nut—is a type of fastener with a closed end that covers and protects the exposed threads of a bolt or stud. The top of the nut is domed or capped, while the bottom is threaded like a standard hex nut.

The primary purpose of an enclosed nut is protection and appearance. The closed end shields the bolt threads from dirt, moisture, and corrosion, preventing damage that could make disassembly difficult later. At the same time, it provides a clean, finished look, hiding the otherwise sharp or unsightly end of the bolt. This makes enclosed nuts popular in automotive, architectural, furniture, and machinery applications, where both durability and aesthetics matter.

Functionally, enclosed nuts are used just like regular nuts—they thread onto a bolt or stud to clamp components together. However, the internal depth of the threads is limited by the cap, meaning they are suitable only when the bolt or stud does not extend beyond the nut’s height.

They are typically made from steel, stainless steel, brass, or aluminum, and may be chrome-plated, zinc-plated, or polished for corrosion resistance and visual appeal. In automotive uses, for example, chrome acorn nuts are common on wheel lugs, protecting threads from road grime while adding a decorative finish.

End Mill

An end mill is a cutting tool used in milling machines and CNC machining centers for removing material from a workpiece to create precise shapes, profiles, holes, and surface finishes. It is one of the most versatile tools in metalworking, woodworking, and plastics machining, capable of cutting in multiple directions—axially (downward into the material) and radially (sideways across the surface).

Unlike a drill bit, which can only cut in one direction (axially), an end mill is designed with cutting edges on both its tip and sides, allowing it to perform operations such as slotting, contouring, facing, pocketing, and profiling.

Design and Construction

An end mill typically consists of:

- A shank, which is clamped into the milling machine’s collet or tool holder.

- A fluted cutting section, which features helical grooves (called flutes) that form sharp cutting edges and help remove chips during machining.

- A cutting tip, which may be flat, ball-shaped, or specially contoured depending on the type of cut desired.

End mills come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and geometries to suit specific applications:

- Flat end mills: Create sharp edges and flat-bottomed slots.

- Ball nose end mills: Used for 3D contouring, sculpted surfaces, and smooth finishes.

- Corner radius end mills: Reduce tool wear and improve part strength at internal corners.

- Roughing end mills: Have serrated edges to remove large amounts of material quickly.

Materials and Coatings

High-performance end mills are typically made from high-speed steel (HSS) or carbide, with coatings such as TiN (Titanium Nitride), TiCN, or AlTiN that reduce friction, improve heat resistance, and extend tool life.

Applications

End mills are used in a wide range of industries—aerospace, automotive, mold-making, and manufacturing—to machine materials such as steel, aluminum, brass, titanium, and plastics. They are especially critical in precision CNC milling, where intricate geometries and tight tolerances are required.

End Plate Connection

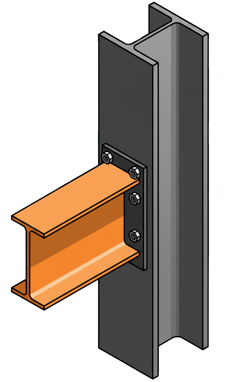

An end plate connection is a type of structural steel joint where a flat steel plate (the end plate) is welded to the end of a beam, column, or member, and then bolted to another structural element—typically another beam, column flange, or a supporting plate. It is one of the most common connection types used in steel construction, bridges, frames, and machinery assemblies, prized for its simplicity, strength, and ease of installation.

In this connection, the end plate acts as a load-transfer interface. The plate is first welded to the beam or member in the fabrication shop, ensuring strong, controlled welds. Once at the site, the plate is bolted to the mating structure using high-strength bolts (often pre-tensioned). This design allows the connection to be both robust and demountable, making maintenance and assembly straightforward.

There are two main categories of end plate connections:

- Simple (shear) end plate connections, which primarily carry shear forces. These are common in secondary framing or beams connecting to girders.

- Moment-resisting end plate connections, where the plate and bolts are arranged to resist bending moments as well as shear, making them suitable for rigid frame structures or moment frames.

In engineering design, end plate thickness, bolt grade, and bolt pattern are carefully chosen to prevent failure through plate yielding, bolt shear, or prying action. The plate must be stiff enough to transmit loads without excessive deformation but ductile enough to handle moment redistribution.

Endurance Limit

The fastener endurance limit is the maximum stress a fastener can endure for an essentially infinite number of load cycles without failing from fatigue. It represents the stress threshold below which a fastener can be repeatedly loaded and unloaded without developing cracks. This property is especially important for bolts, studs, and screws used in engines, turbines, machinery, and bridges, where vibration and cyclic loading are common. If stresses remain below the endurance limit, the fastener can theoretically last indefinitely; if stresses exceed it, fatigue failure can occur even at levels far below the tensile strength.

As an example: Consider a medium-carbon steel bolt with an ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of 800 MPa. The endurance limit for steels is typically around 40–50% of UTS. In this case, the endurance limit would be approximately 320–400 MPa. If the bolt is subjected to a cyclic tensile stress of 300 MPa, it should survive millions of cycles without failure. But if the applied cyclic stress is 450 MPa, the bolt may eventually fail from fatigue even though 450 MPa is well below the 800 MPa tensile strength. Factors like surface finish, corrosion, thread design, and preload can reduce the effective endurance limit in real-world applications.

Engine Mount Stud

An engine mount stud is a specialized threaded fastener used to secure an engine to its mounting brackets or frame while helping to isolate and absorb vibration. It’s a critical component in both automotive and industrial machinery applications, ensuring that the engine remains firmly in place under high loads, temperature fluctuations, and constant motion.

Structurally, an engine mount stud is a double-ended stud (or sometimes a partially threaded rod) with threads on both ends and a smooth, unthreaded section in the middle. One threaded end is screwed into the engine block or transmission housing, while the other end extends outward to pass through the engine mount and frame bracket, where it’s secured with a washer and nut. This design allows for precise alignment, easy engine installation or removal, and strong load-bearing capability.

The stud itself is usually made from high-strength alloy or stainless steel to withstand engine heat, torque, and vibration. Some designs may include coatings such as zinc plating, phosphate, or black oxide for corrosion resistance. In performance or heavy-duty applications, heat-treated or high-tensile studs are used to handle extreme stresses without loosening or stretching.

Engine mount studs are commonly found in automobiles, motorcycles, marine engines, and industrial generators—essentially anywhere an engine must be securely fixed to a chassis while allowing for controlled vibration damping through rubber or polyurethane engine mounts.

EPDM Washer

An EPDM washer is a type of washer made from EPDM rubber, a synthetic rubber material known for its excellent resistance to weathering, UV rays, ozone, and environmental elements. EPDM stands for ethylene propylene diene monomer, which is a type of durable and flexible elastomer.

Epoxy

Epoxy is a corrosion-resistant coating applied to fasteners using a dip-spin process. Known for its durability and strong barrier properties, epoxy can offer up to 1,000 hours of salt spray protection and helps prevent degradation from UV exposure, moisture, oxidation, chemicals, and general wear. The primary drawback of epoxy coatings is their thickness, which can sometimes interfere with thread fit, especially in precision applications.

Appearance - Epoxy coatings typically have a thick, matte finish and may appear in a range of colors depending on the formulation, most commonly in shades of gray, black, or brown.

Equalizer Bolt

An equalizer bolt is a specialized heavy-duty fastener used in mechanical, structural, and suspension systems to distribute loads evenly across connected components. Its primary function is to ensure that forces such as weight, vibration, or tension are balanced, preventing uneven stress, misalignment, and premature wear. The name “equalizer” comes from this ability to equalize or balance forces throughout a system, improving its stability, safety, and overall performance.

In vehicle and trailer suspension systems, equalizer bolts are a key component connecting the equalizer beam or bar, which pivots to balance weight between the front and rear leaf springs. As the vehicle moves over uneven terrain, the bolt allows the suspension to flex and shift loads evenly, creating a smoother ride and reducing strain on the springs and frame. In industrial machinery and conveyor systems, equalizer bolts help maintain proper alignment and tension in belts, chains, and other moving parts. They also appear in cranes, lifting rigs, and agricultural equipment, where they distribute tensile loads across multiple cables, arms, or linkages, ensuring that no single point bears excessive stress.

Typically made from hardened or alloy steel, equalizer bolts are built to withstand high shear forces and dynamic motion. They often incorporate bushings, washers, and locking nuts to maintain alignment under load, and many are equipped with grease fittings (zerk fittings) to allow regular lubrication, reducing wear and extending service life.

Escutcheon Screw

An escutcheon screw is a decorative or functional fastener used to secure an escutcheon plate—a trim or cover plate that conceals and protects openings around fixtures, hardware, or pipes. The term “escutcheon” refers to the plate itself, which provides a clean, finished appearance where components such as faucets, door knobs, keyholes, or plumbing connections meet a wall or surface. The escutcheon screw’s role is to hold that plate firmly in place.

These screws are typically small and finely finished, designed to blend aesthetically with the hardware they accompany. They are often made from brass, stainless steel, or chrome-plated steel, matching the color and finish of the escutcheon plate—such as polished chrome, brushed nickel, or antique brass. Some designs include decorative heads (flat, round, or domed) to enhance the overall appearance, while others are concealed beneath snap-on covers for a smooth, seamless look.

Functionally, escutcheon screws are used in plumbing fixtures (for example, attaching the trim plate around a shower valve or sink faucet), door hardware (securing keyhole plates or handle trims), and architectural fittings (such as railing mounts or wall plates). They may also be used in electrical or HVAC applications, where an escutcheon plate covers a pipe, conduit, or cable entry point.

ESD Fastener

An ESD fastener (Electrostatic Discharge fastener) is a specialized fastener designed to prevent the buildup and discharge of static electricity that could damage sensitive electronic components or ignite flammable materials. These fasteners are used in environments where electrostatic control is essential—such as in electronics manufacturing, cleanrooms, aerospace, semiconductor assembly, and defense applications.

Unlike standard fasteners, ESD fasteners are made from or coated with conductive or dissipative materials that allow electrical charges to safely flow through them to a grounded surface. This prevents localized static charge accumulation that could otherwise lead to a sudden discharge (an ESD event).

There are generally two categories of ESD fasteners:

- Conductive fasteners, which provide a low-resistance path to ground, quickly equalizing potential differences between components and surfaces.

- Static-dissipative fasteners, which allow charges to bleed off more slowly, preventing arcing or sparks that could damage sensitive equipment.

Common materials used include stainless steel with conductive coatings (like zinc-nickel or black oxide), carbon-filled polymers, brass, or aluminum alloys. In some cases, non-metallic ESD fasteners are made from carbon-loaded nylon or polyetherimide (PEI), which balance strength with electrical performance while remaining lightweight and corrosion-resistant.

In practical use, ESD fasteners are often found securing circuit boards, grounding panels, racks, and housings in electronic devices or production equipment. By maintaining electrical continuity throughout assemblies, they help ensure compliance with ESD safety standards such as ANSI/ESD S20.20 and IEC 61340.

Eutectic Blend

A eutectic blend is a specific mixture of two or more substances—usually metals, alloys, or chemical compounds—that melts and solidifies at a single, sharply defined temperature, which is lower than the melting point of any of the individual components. This special composition is called the eutectic point, and the resulting mixture behaves almost like a pure substance in the way it melts and freezes.

In a eutectic blend, the components do not dissolve into one another to form a single uniform solid solution. Instead, when the mixture solidifies, it forms a distinct, fine-scale microstructure—often alternating layers or interlocking crystals of the individual phases. This microstructure can provide desirable properties such as improved machinability, enhanced strength, or lower melting temperature. Because eutectic mixtures melt uniformly at a single temperature rather than over a range, they are widely used in solders, brazing alloys, casting alloys, and fusible materials where precise melting behavior is important.

A classic example is the eutectic solder alloy of 63% tin and 37% lead (Sn–Pb), which melts sharply at 183°C, lower than either pure tin or pure lead. In industrial metals, eutectic structures also appear in systems like aluminum–silicon, iron–carbon (where the eutectic point produces ledeburite), and many others. Because the eutectic composition yields both predictable melting behavior and a unique microstructure, eutectic blends are critical in metallurgy, manufacturing, electronics, and materials engineering.

Expansion Bolt

An expansion bolt is a type of fastener used to secure heavy loads to materials like concrete, brick, or stone by expanding within a drilled hole to create a tight, friction-based anchor. Unlike ordinary screws or bolts that rely on threads for grip, expansion bolts use mechanical expansion to hold firm against the walls of the base material, making them ideal for structural and load-bearing applications.

The basic design of an expansion bolt includes a bolt or threaded stud, an expansion sleeve or shell, and a cone-shaped plug or wedge. When the bolt is tightened, it pulls the cone into the sleeve, forcing the sleeve to expand outward and press tightly against the sides of the hole. This frictional force locks the bolt securely in place. Some versions expand mechanically when torqued, while others rely on hammering or chemical adhesives (like epoxy) for additional strength.

Expansion bolts come in several varieties depending on the application:

- Wedge anchors – common for structural applications like mounting machinery, handrails, or heavy equipment to concrete.

- Sleeve anchors – versatile and used in softer masonry materials.

- Drop-in anchors – designed to sit flush with the surface, often used for overhead or suspended installations.

- Shield anchors – provide excellent holding power in brick or stone walls.

Because of their strength and reliability, expansion bolts are widely used in construction, infrastructure, and industrial equipment mounting, ensuring stable, vibration-resistant connections that can withstand shear and tension forces.

External Retaining Ring

An external retaining ring—also called an external circlip or snap ring—is a spring-steel ring that snaps into a groove machined around the outside of a shaft. Once seated, it forms a shoulder that blocks axial movement of parts such as bearings, gears, spacers, and pulleys. “External” indicates it fits around a shaft; the counterpart is an internal retaining ring that seats inside a bore.

During installation, the ring is elastically expanded and then springs back into the shaft groove. Thrust loads are transferred from the retained parts through the ring to the groove wall or shoulder. Most rings are made from carbon spring steel or stainless steel, with finishes like phosphate or zinc for corrosion protection. Sizing is based on shaft diameter, and groove width and depth follow standards such as DIN 471 and ASME B18.27 for external rings.

Common styles include the standard circlip with lug holes, installed with snap-ring pliers; the E-ring, which pushes radially into a groove for quick installation; the spiral (spiral-wound) ring, which winds into the groove to provide 360° contact without lugs; and the constant-section (C-ring), which has a uniform rectangular cross-section suited to high loads and impact.

For installation, use proper pliers or applicators and avoid over-expanding the ring. Many stamped circlips have a sharp “punch” edge and a rounded “die” edge—orient the sharp edge toward the primary thrust direction for the best retention. Always verify groove dimensions and shaft chamfers, and select material and finish appropriate to the environment and load.

External Thread

A helical ridge formed on the outside surface of a cylindrical part, such as a bolt or screw. External threads are designed to mate with internal threads, allowing the fastener to be securely screwed into nuts, tapped holes, or other threaded components.

Externally Threaded Inserts

Externally Threaded Inserts are fastener components designed to provide a strong, reusable threaded connection inside a softer or weaker material, such as plastic, wood, or soft metals. They have external threads on the outside surface that allow them to be securely screwed or pressed into a pre-drilled hole in the base material, creating a durable mounting point.

Extruding

A metal-forming process where material is pushed through a shaped die to create a specific, continuous profile. In fastener manufacturing, it's used to produce raw material like wire, or to form internal features such as holes within parts.

Eye Bolt

An eye bolt is a type of fastener that features a loop (or "eye") at one end and a threaded shaft on the other. It’s used primarily as a point for attaching ropes, cables, chains, or hooks to lift, secure, or support loads.

Eye Lag Screw

An Eye Lag Screw (also called an Eye Lag Bolt) is a heavy-duty fastener that combines features of an eye bolt and a lag screw. It has a threaded screw shaft designed to be driven directly into wood or other materials without a nut, and a closed loop ("eye") at the head.

Eye Nut

An eye nut is a specialized type of nut with a built-in loop or “eye” on one end, designed to provide a secure attachment point for lifting, pulling, rigging, or anchoring loads. It combines the threaded functionality of a standard nut with the utility of a lifting eye, making it an essential component in material handling, construction, marine, and industrial applications.

Structurally, an eye nut consists of a threaded base—which screws onto a bolt, threaded rod, or stud—and a circular or oval-shaped ring that forms the eye. Once tightened, the eye serves as a strong connection point for hooks, cables, ropes, shackles, or chains. Because the load is transferred through both the thread and the eye, eye nuts are made from forged or machined steel, stainless steel, or alloy steel, and are often heat-treated and galvanized or zinc-plated for corrosion resistance and strength.

There are several variations of eye nuts, each tailored to specific load directions and environments. Plain pattern eye nuts are designed for vertical loads, while shouldered eye nuts include a reinforced collar that allows for angular or side loading without deforming or weakening the joint. Some types feature swiveling or pivoting eyes to accommodate dynamic loads or prevent twisting of cables.

Eye nuts are widely used in lifting assemblies, hoists, rigging systems, and machinery installations. In marine settings, they serve as anchor points on boats or docks. In construction and manufacturing, they are used to lift heavy equipment, molds, or structural components safely.

Eye Pin

An eye pin is a type of fastener or wire component that features a straight shank with a loop (or “eye”) at one end. The eye forms a small circular or oval opening that allows it to connect, hang, or link to other components. Eye pins are commonly used in jewelry making, light mechanical linkages, and small-scale fastening applications where a simple attachment or pivot point is needed.

In jewelry and craft applications, an eye pin is typically made of a thin metal wire—such as brass, copper, stainless steel, or sterling silver—and used to string beads or charms. The straight end is inserted through a bead or component, and the other end is often bent or formed into another loop, creating a connection between multiple elements like chains or pendants.

In industrial and mechanical contexts, eye pins can be larger and more robust, resembling miniature versions of eye bolts. These are used in assemblies that require light-duty attachments, guiding, or alignment. The eye portion may be used for tying, hooking, or securing wires and cables.

Eye pins differ from head pins, which have a flat or rounded head instead of a loop. While a head pin stops a bead or component from slipping off, an eye pin provides a joining point that allows movement, rotation, or connection to another fastener.

Eyelet Fastener

An eyelet fastener is a small metal or plastic ring with a flared or collared edge, designed to reinforce a hole or provide a durable opening for threading, lacing, or attaching components. It’s a versatile fastening device used across industries to prevent tearing, fraying, or wear around holes in fabric, leather, plastic, sheet metal, and other materials.

Structurally, an eyelet consists of a cylindrical barrel (or shank) and a flanged head. During installation, the barrel is inserted through a pre-punched hole and then crimped, rolled, or flared on the opposite side using a hand tool or press. This process secures the eyelet firmly in place, sandwiching the material between the two flared ends to create a smooth, reinforced opening.

Eyelet fasteners come in various materials—most commonly brass, aluminum, stainless steel, nickel-plated steel, or plastic—depending on the required strength, corrosion resistance, and appearance. They can be found in several finishes, from polished and colored coatings to industrial-grade metals.

In textiles and leather goods, eyelets are used in shoes, belts, tarps, tents, and corsets to provide durable lacing holes. In stationery and office supplies, they reinforce binding holes in tags, folders, and labels. In industrial and electronic applications, eyelets can act as miniature bushings, rivet-like connectors, or electrical terminals, securing wiring or components.

While similar to grommets, eyelets are typically smaller and lighter-duty, used for decorative or light reinforcement, whereas grommets are heavier and designed for high-stress environments like sails or industrial curtains.