Resources

Glossary

Galling

Galling is a type of wear and surface damage that occurs when two metal surfaces slide against each other under pressure, causing material to transfer from one surface to the other. It is sometimes referred to as a form of “cold welding” because the high friction and localized adhesion make the surfaces stick together and tear apart unevenly. This often results in rough, damaged threads, seized fasteners, or scratched and scored surfaces.

In fasteners, galling is most common with stainless steel, aluminum, and titanium bolts and nuts, because these metals have a tendency to form adhesive bonds when rubbed together. As torque is applied, microscopic high points (asperities) on the threads weld together under pressure. When the fastener continues to turn, these welded spots tear, pulling material from one surface to the other. This not only damages the fastener but can also cause it to seize, making removal extremely difficult.

Contributing factors to galling include high loads, lack of lubrication, soft or ductile metals, high-speed installation, and repeated tightening/loosening of the same fastener. The risk is especially high in applications with stainless steel fasteners used without lubrication.

Prevention methods include:

- Using anti-seize lubricants or specialized thread lubricants.

- Choosing fasteners with surface treatments or coatings (such as PTFE, zinc, or nitriding).

- Reducing installation speed and avoiding power tools that generate heat and friction.

- Mixing dissimilar metals (e.g., using a stainless steel bolt with a different nut alloy) to reduce adhesion.

- Using fasteners specifically designed with anti-galling properties.

Galvanic Corrosion

Galvanic corrosion is a form of electrochemical corrosion that occurs when two different metals are in electrical contact in the presence of an electrolyte, such as water that contains salts, acids, or other conductive impurities. This situation creates a galvanic cell, where one metal functions as the anode and the other as the cathode. The anode is the more active metal, meaning it has a greater tendency to give up electrons, and therefore it corrodes more quickly than it would on its own. The cathode, being the more noble metal, is protected from corrosion. A common example is seen when steel and copper are connected in a marine environment: the steel, acting as the anode, corrodes rapidly, while the copper, as the cathode, remains unharmed.

The severity of galvanic corrosion is influenced by several conditions. The greater the difference in electrochemical potential between the two metals, the faster corrosion will occur. The conductivity of the electrolyte also plays a major role, with saltwater being particularly aggressive in accelerating the process. Additionally, the relative size of the metals in contact affects the outcome; a small anode connected to a large cathode will corrode at a much faster rate due to the disproportionate distribution of current.

To prevent or reduce galvanic corrosion, engineers employ several strategies. Metals that are close to each other in the galvanic series are often chosen to minimize potential differences. Coatings, insulators, or paints can be applied to separate the metals electrically. Protective measures such as galvanization or the use of sacrificial anodes, like zinc on ship hulls, can redirect corrosion to a controlled, replaceable material. Designers may also consider the ratio of exposed metal areas to reduce the imbalance between anodic and cathodic surfaces.

In fasteners and construction, galvanic corrosion is especially important to address because it can compromise the integrity of joints and assemblies. A classic example is the use of stainless steel bolts in aluminum structures. Without proper insulation or coatings, the aluminum can corrode quickly in a moist environment, weakening the structure and leading to premature failure. This makes galvanic corrosion a critical factor in selecting and designing fastening systems for long-term durability.

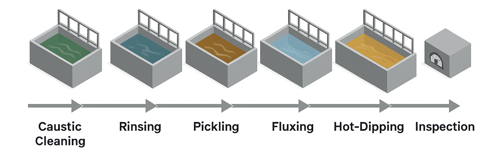

Galvanizing Process

The galvanizing process for steel materials begins with caustic cleaning (degreasing), where steel parts are immersed in a hot alkaline solution, typically caustic soda. This step removes oils, grease, dirt, and organic contaminants from the surface. The parts are then rinsed in water to eliminate residues before moving to the next stage. After degreasing, the steel undergoes pickling (acid cleaning), which involves dipping the parts into a dilute acid bath—commonly hydrochloric acid (HCl) or sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄). This treatment removes mill scale, rust, and oxides that remain on the steel surface. Another water rinse follows to prevent acid carryover into later steps.

Once the steel is clean, it enters the fluxing stage. Here, the steel is dipped into a flux solution, typically zinc ammonium chloride (ZnCl₂ + NH₄Cl), which coats the surface. The flux prevents oxidation before immersion in molten zinc and helps ensure proper bonding between the steel and zinc during galvanizing. In some cases, a dry flux layer is applied and dried on the steel surface. When this method is used, a drying step may follow to reduce spattering when the steel is submerged into the molten zinc bath.

The core of the process is hot-dip galvanizing, where the steel is immersed in a bath of molten zinc maintained at about 450 °C (840 °F). At this temperature, the zinc metallurgically reacts with the steel surface, forming a series of zinc-iron alloy layers that are tightly bonded to the steel, topped with an outer layer of pure zinc. This metallurgical bond makes the coating exceptionally durable and resistant to peeling or flaking. After being withdrawn from the zinc bath, the parts undergo cooling and solidifying, either by air cooling or water quenching, which hardens the coating and prepares the galvanized product for handling.

Finally, the parts undergo inspection to verify the quality of the coating. This includes checking for coating thickness, adhesion, and uniform coverage. Inspections are carried out through visual examination, thickness measurements, and adherence testing to ensure the finished galvanized coating meets industry standards. The end result is a galvanized steel product with a protective zinc coating that provides both a physical barrier and sacrificial protection against corrosion, significantly extending the material’s service life in harsh environments.

Gasket Leakage

Gasket leakage is the unintended escape of a fluid (gas or liquid) through a gasketed joint because the gasket–flange interface does not maintain a continuous, sufficiently compressed sealing barrier. Leakage occurs when the contact stress on the gasket is too low, non-uniform, or becomes compromised, allowing a leak path to form through surface imperfections, gasket porosity, micro-channels, or along the gasket edges.

Leakage is commonly caused by insufficient bolt preload, uneven tightening, or loss of clamp load over time due to gasket seating/relaxation, embedment, creep (cold flow), or vibration. It can also be driven by thermal cycling, which repeatedly changes relative expansion between bolts, flanges, and the gasket, altering gasket stress and potentially “working” the joint until sealing stress drops below what’s required. Additional contributors include incorrect gasket selection for the service (pressure, temperature, chemical compatibility), damaged or warped flange faces, improper surface finish, misalignment, and bolt or nut issues (yielding, galling, wrong lubrication, or excessive friction variability that prevents achieving target preload).

Gasket leakage is often described by where it occurs: internal leakage (past a partition in heat exchangers), external leakage (to atmosphere), or blowout (a sudden gasket failure from excessive pressure or loss of restraint). Preventing it typically centers on achieving and retaining the correct gasket stress using proper gasket type, flange finish, bolt material, tightening method (multi-pass patterns, controlled torque, tensioning), and, when required, post-assembly retorque practices such as a relaxation pass.

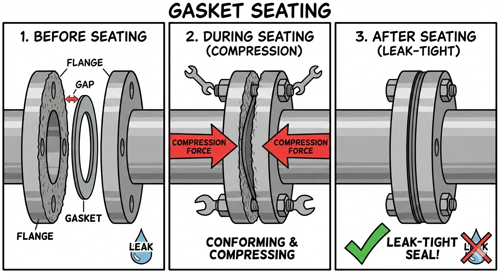

Gasket Seating

Gasket seating is the process by which a gasket is compressed and conformed between two mating surfaces during bolt-up so it creates a continuous, leak-tight seal. As the fasteners are tightened, the joint applies compressive stress that causes the gasket to flow, crush, or deform (depending on gasket type), filling in surface roughness, waviness, and minor imperfections so there are no continuous leakage paths.

Gasket seating typically happens in two stages: an initial seating phase during tightening where the gasket’s thickness reduces and its contact area stabilizes, and a short-term settlement/relaxation phase afterward where additional compression loss can occur due to creep, cold flow, embedment, and surface “bedding-in.” This is why gasketed joints are often tightened in multiple passes and patterns and may require a relaxation pass (retorque) after a dwell period to restore lost bolt load and maintain the gasket stress needed for sealing.

The amount of gasket seating required depends on gasket construction (soft sheet, spiral wound, kammprofile, PTFE, graphite, etc.), flange surface finish, temperature, and internal pressure, and it’s often managed by specifying a minimum gasket seating stress (sometimes expressed as a seating factor in design methods) to ensure the gasket is sufficiently compressed without being over-crushed or damaged.

Gauge

Gauge is a numerical sizing system used to describe the diameter or wire size of certain fastener types, most commonly sheet-metal screws, wood screws, nails, pins, brads, and staples. Instead of using fractional inch or metric measurements, gauge assigns a number—such as #6, #8, or #10—that corresponds to a specific, standardized diameter. These numbers don’t increase in a perfectly linear way, but in general, a higher gauge number indicates a larger screw diameter in threaded fasteners, while for wire-based products like nails or staples, a lower gauge number means thicker wire and a higher number means thinner wire. The meaning changes depending on the product category, but the underlying idea is the same: gauge is a shorthand reference to physical size.

In the fastener world, gauge is used heavily for sheet-metal screws, where sizes like #6, #8, and #10 refer directly to major diameters and have long been industry standard. Traditional wood screws also historically used gauge, though many now reference fractional or metric diameters. In nails, brads, and wire products, gauge directly relates to wire thickness and affects how the fastener penetrates material, how much holding strength it has, and what tools it fits. Gauge also appears indirectly when selecting fasteners for sheet metal, since the sheet’s thickness may also be listed in gauge (e.g., 16-gauge steel), which influences pilot hole sizes and screw selection.

Understanding gauge is important in industrial and distribution settings because it affects fit, strength, compatibility with tools, and performance in different materials. A #6 screw will not behave the same as a #8 screw in a pre-drilled hole, and a 16-gauge brad will not fit into an 18-gauge nailer. Despite being an older measurement system, gauge remains deeply rooted in North American fastener terminology, and distributors often encounter it when cross-referencing specs, replacing legacy parts, or helping customers identify the correct size.

Geomet®

A water-based zinc-aluminum flake coating system that provides high corrosion resistance without the use of hexavalent chromium. Commonly used on automotive and industrial fasteners, Geomet® coatings offer thin, uniform layers that resist heat, salt spray, and chemical exposure while maintaining consistent torque tension performance.

Gimlet Point

A gimlet point is a sharp, tapered screw point designed to start quickly and cut into wood with minimal splitting and without needing a pre-drilled pilot hole in many applications. It’s essentially a wood-screw style point: the tip is needle-like and the first threads are shaped to bite and pull the screw in, similar to how a gimlet tool bores into wood.

You’ll see gimlet points most often on wood screws, lag screws, and some self-tapping screws intended for wood or softer materials, where fast starts and strong thread engagement in fibers are the goal.

Gland Nut

A gland nut is a specialized fastening component designed to secure and compress a gland or packing in place, usually within mechanical or electrical systems that require reliable sealing. By tightening the gland nut, axial force is applied to compress the gland or packing material, which creates a seal that prevents the escape of fluids or gases, and in some cases protects against the ingress of dust, dirt, or moisture. Importantly, this type of seal allows for movement of a shaft, rod, or cable while maintaining system integrity.

In terms of design and construction, a gland nut is generally hexagonal or round with external flats so it can be tightened with a wrench. It has internal threads that allow it to screw onto a housing, stuffing box, or fitting. Inside the assembly, the gland nut presses against a gland follower or directly onto a packing material, such as graphite, PTFE, or elastomeric seals. In cable gland systems, the gland nut often squeezes a rubber or plastic grommet around the outer sheath of a cable, providing both sealing and strain relief. Gland nuts are commonly made from brass, stainless steel, or carbon steel for strength and durability, though engineered plastics are sometimes used for lightweight and corrosion-resistant applications.

The purpose and function of a gland nut are twofold: to create a controlled seal and to secure a component. In mechanical equipment such as pumps and valves, the gland nut compresses the packing material around a moving shaft or rod to prevent fluid leakage while still allowing motion. In electrical or instrumentation systems, the gland nut clamps a cable gland tightly around a cable, preventing it from being pulled out and maintaining protection against dust or water ingress. These features make gland nuts essential for both sealing and safety in demanding environments.

Common applications of gland nuts include pumps and valves, where they secure packing around shafts and valve stems; hydraulic and pneumatic cylinders, where they prevent fluid leakage along moving rods; and electrical cable glands, where they clamp and seal cables entering enclosures to provide ingress protection and strain relief. They are also widely used in marine, oil and gas, and other industrial sectors where protection against leakage and environmental exposure is critical.

The advantages of gland nuts are their simplicity and reliability. They provide an adjustable and cost-effective sealing solution compared to more complex systems like mechanical seals. They can often be reused or adjusted to compensate for packing wear, and they are available in a wide range of materials to suit corrosive, high-temperature, or otherwise demanding environments.

However, there are limitations to gland nuts. They require periodic maintenance, as packing materials compress and wear over time, which reduces their sealing effectiveness. The friction created between the packing and the moving shaft can cause wear, generate heat, and result in energy loss. Gland nuts are not ideal for extremely high-pressure or zero-leakage applications, where mechanical seals are better suited. Additionally, over-tightening can damage the packing or the shaft, leading to leaks or premature failure.

Grade

A fastener grade is a standardized classification that indicates the strength, material properties, hardness, and performance capabilities of a bolt, screw, or similar fastener. Grades tell you how strong the fastener is, how it was manufactured (such as material type and heat treatment), and what applications it is suitable for.

In the fastener world, grades are essential because not all bolts are created equal—some are meant for light-duty household use, while others must withstand the extreme loads of heavy machinery, automotive suspensions, or structural steel assemblies. A grade ensures that no matter who manufactures the fastener, its minimum strength and performance characteristics remain consistent.

In the SAE (inch-series) system, common grades include Grade 2, Grade 5, and Grade 8, each with specific tensile strength, yield strength, hardness, and identification markings. Metric fasteners use a different system (e.g., Class 8.8, 10.9, 12.9) but serve the same purpose—defining strength levels so engineers, mechanics, and distributors know exactly what they’re working with.

Fastener grades are especially important in industrial settings because using the wrong grade can lead to joint failure, equipment damage, or safety hazards. Distributors like Earnest Machine rely on grades to cross-reference, recommend alternatives, and ensure customers are using the correct fastener for the load, environment, torque requirements, and safety standards of their application.

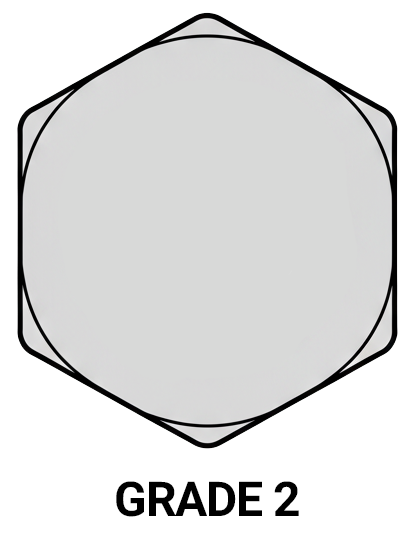

Grade 2 (SAE)

A Grade 2 fastener is a low-carbon steel bolt or screw that represents the basic, entry-level strength grade in the SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers) grading system used primarily in the United States. These fasteners are typically made from low-carbon steels such as 1006, 1008, or 1010 and are not heat-treated, which keeps their strength lower but makes them inexpensive, ductile, and suitable for general-purpose applications.

In industrial and fastener-distribution environments, Grade 2 fasteners are considered non-critical, light-duty hardware. They are commonly used in non-structural, non-load-bearing assemblies, household applications, light machinery, basic construction, appliance manufacturing, and farm equipment where high tensile or shear strength is not required. Their typical mechanical properties include a minimum tensile strength around 60,000 psi for bolts under 1" diameter and roughly 55,000 psi for bolts 1" and above—significantly lower than Grade 5 or Grade 8.

Grade 2 bolts are usually identified by a plain head with no markings (hex bolts without radial lines). In distribution, they are often supplied zinc-plated, hot-dip galvanized, or plain and are widely stocked due to their versatility and low cost. For situations requiring structural integrity, vibration resistance, high torque, or elevated temperature performance, Grade 2 fasteners are not appropriate and are replaced by higher-grade fasteners like Grade 5, Grade 8, or alloy/metric equivalents (Class 8.8, 10.9, etc.).

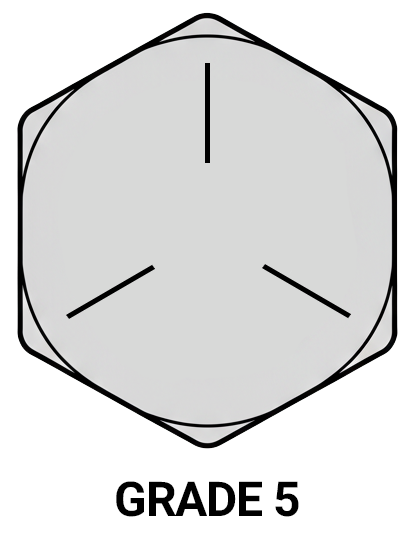

Grade 5 (SAE)

A Grade 5 fastener is a medium-strength, heat-treated carbon steel bolt or screw defined by the SAE J429 standard. It represents the “general-purpose high-strength” category in the SAE grading system—stronger than Grade 2, but not as strong as Grade 8. Grade 5 is one of the most widely used fastener grades in North American industrial, automotive, and machinery applications.

Grade 5 bolts are typically made from medium-carbon steel (such as 1038, 1541, or similar steels) and are quenched and tempered to increase their tensile strength, hardness, and toughness. Their mechanical properties are significantly higher than Grade 2, with a minimum tensile strength of about 120,000 psi (for diameters up to 1 inch). This added strength makes them suitable for load-bearing assemblies, machinery, automotive components, agricultural equipment, heavy-duty brackets, structural joints, and general industrial equipment where durability and performance are essential.

Grade 5 fasteners are easy to identify: the head of a standard hex bolt will have three radial lines, evenly spaced, indicating its grade. They are often supplied in zinc-plated, plain/oil finish, or phosphate and oil variants. Because they offer an excellent balance of strength, cost, and availability, Grade 5 bolts are one of the most commonly stocked fastener grades in distribution, especially for MRO and OEM customers.

Grade 8 (SAE)

A Grade 8 fastener is a high-strength, high-performance bolt or screw made from medium-carbon alloy steel and heat-treated to achieve some of the highest mechanical properties in the SAE J429 grading system. Grade 8 bolts are significantly stronger than both Grade 2 and Grade 5 and are used whenever the joint must withstand high loads, shock, vibration, or critical structural forces.

Grade 8 fasteners are typically manufactured from steels such as medium-carbon alloy (like 4037 or 4140) and are quenched and tempered to achieve very high hardness and tensile strength. Their minimum tensile strength is approximately 150,000 psi, and their yield strength is around 130,000 psi, making them one of the strongest readily available standard inch-series bolt grades.

In practical industrial settings, these fasteners are used in heavy equipment, automotive suspensions, engine assemblies, agricultural machinery, off-highway vehicles, structural support systems, hydraulic components, and any application where failure would be dangerous or costly. They handle high clamping force, resist deformation under heavy loads, and hold up well in dynamic or vibration-prone environments.

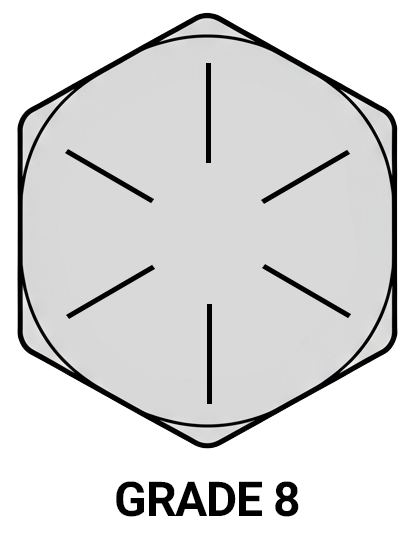

Grade 8 hex bolts are easily identified by six radial lines on the head, which is a universal SAE marking. They are usually supplied in yellow zinc, clear zinc, phosphate and oil, or plain finishes depending on corrosion requirements. For customers choosing between grades, Grade 8 is ideal when maximum strength is required, while still being compatible with standard inch-series tooling and thread classes.

Grade Markings

Grade markings are the identification symbols stamped onto the head of a fastener (usually hex bolts) that indicate the fastener’s grade, strength level, and manufacturing standard. These markings allow engineers, mechanics, distributors, and end-users to instantly recognize how strong a bolt is and whether it is suitable for a specific application—without needing packaging, paperwork, or guessing.

In the SAE inch-series system, grade markings appear as radial lines on the bolt head:

- No lines = Grade 2 (low strength, non-critical applications)

- 3 radial lines = Grade 5 (medium strength, heat-treated)

- 6 radial lines = Grade 8 (high strength, heat-treated alloy steel)

The number of lines + 2 equals the grade number. These markings are standardized so that a Grade 5 bolt from one manufacturer matches the properties of a Grade 5 bolt from another.

Metric fasteners use raised numbers instead of lines (like 8.8, 10.9, 12.9), and many specialty fasteners use proprietary or additional symbols to denote manufacturer identity, material type, or compliance with standards such as ASTM, ISO, or SAE J429.

Grade markings serve several critical industrial functions: they help prevent mixing of low-strength and high-strength bolts, ensure safety in structural or load-bearing applications, simplify quality control, and allow distributors to quickly identify inventory. In fastener selection, installation, and inspection processes, grade markings are often the first and most important piece of information used to determine whether a fastener is appropriate for the job.

Grain Bin Bolts

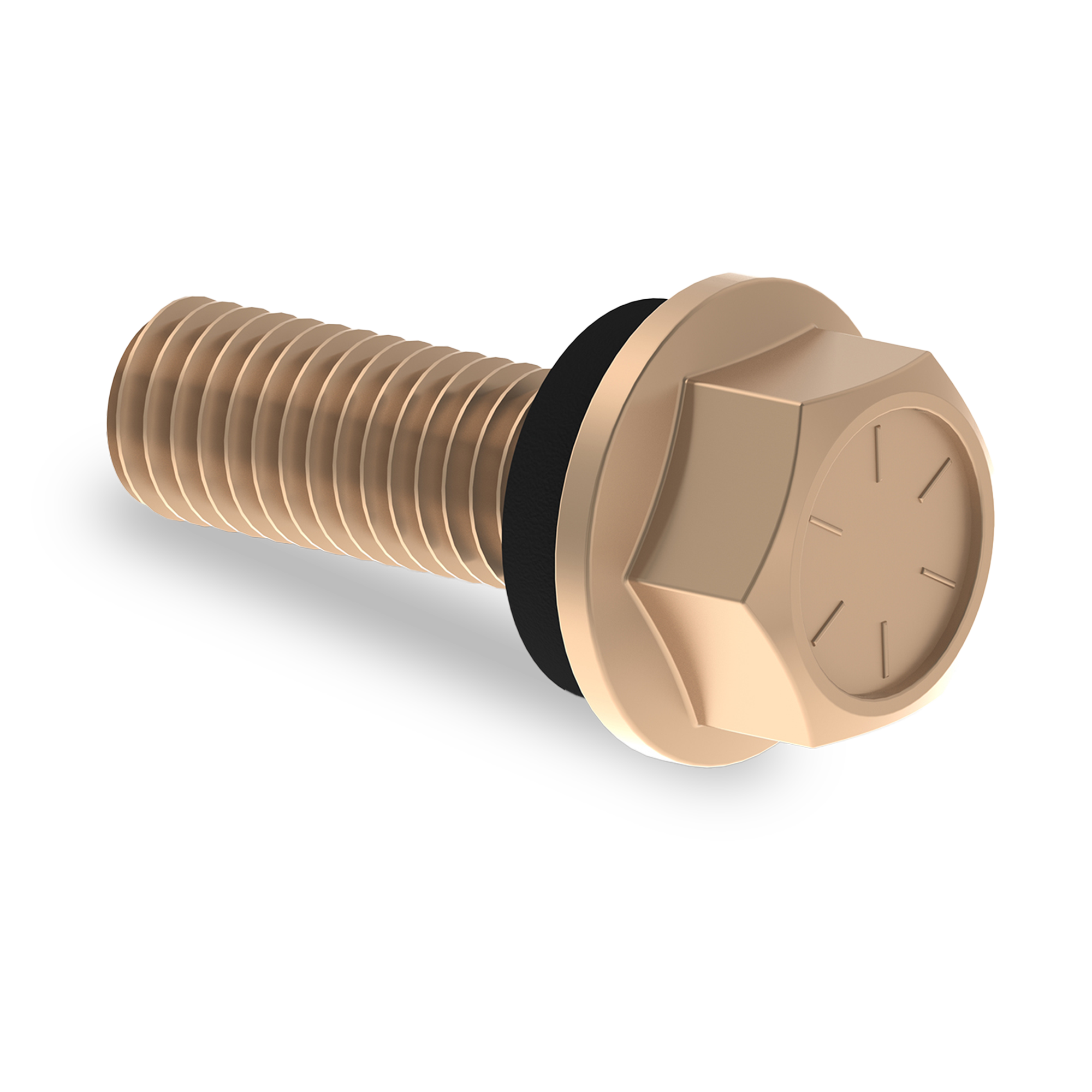

Hex Flange Screws with EPDM Sealing Washers, also known as Grain Bin Bolts, are designed with a recessed flange under the head to fully conform to a rubber washer, creating a watertight and moisture-repellant seal. Earnest Machine's line of product comes preassembled with an EPDM washer, which performs well in extreme weather conditions, meaning the EPDM washer will not dry out or crack in the sun, and it will not become brittle in freezing temperatures.

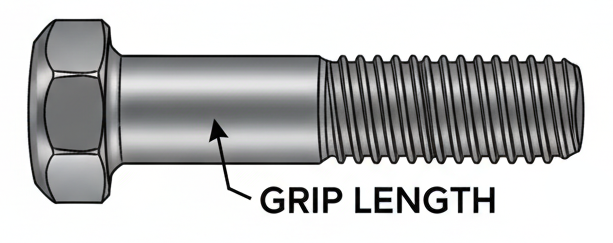

Grip Length

Grip length is the total thickness of the materials being clamped by a bolt, screw, or stud, measured from under the fastener’s head (or nut, in the case of a stud) to the end of the unthreaded portion of the shank. It represents the combined thickness of the clamped parts, not including washers or nuts. The grip length is ideally equal to or slightly greater than the unthreaded shank, ensuring that shear loads are carried by the smooth shank rather than by the threads, which are weaker and more prone to fatigue.

It is different from overall fastener length, since it specifically refers to the section of the fastener engaged with the clamped materials. Grip length is especially important in applications like aerospace, automotive, and structural assemblies, where precision and durability are critical. For example, if two steel plates each 10 mm thick are bolted together, the grip length is 20 mm, regardless of the total bolt length.

Grub Screw

A grub screw, also known as a set screw, is a type of fastener specifically designed to secure one component against another without the need for a nut. Unlike conventional screws, a grub screw has no head—its entire body is threaded, and it is tightened or loosened using a recessed drive such as a hex socket (Allen), slotted, or Torx. This makes it ideal for applications where a flush or hidden fastening solution is required.

In terms of design and construction, grub screws are generally short, fully threaded cylindrical fasteners. Since they lack a head, they sit flush with or below the material’s surface when installed, creating a clean finish. The screw’s working end may be shaped in different styles—flat, cone, cup, dog, or oval—to suit how it grips the mating part. Materials such as alloy steel, stainless steel, and brass are commonly used, with heat treatments or coatings often added to enhance strength and corrosion resistance.

The main function of a grub screw is to lock two parts together by applying pressure at a single point. They are most frequently used to secure rotating components, such as gears, pulleys, or collars, onto shafts. By tightening the screw so that its tip presses directly against the shaft surface or into a prepared recess, the grub screw prevents movement, slippage, and misalignment, even under vibration or torque.

Grub screws have wide applications across industries. In machinery, they secure pulleys, gears, and collars. In electronics and instruments, they lock knobs or dials in place on rotary shafts. The automotive and aerospace industries use them in linkages, couplings, and compact rotating mechanisms where space is restricted. They also find use in furniture and fixtures, holding parts together discreetly without visible fastener heads.

The advantages of grub screws include their compact, flush fit with no protruding head, their ability to provide strong localized locking force, and the availability of various tip styles for different uses. They are also inexpensive and require only basic tools for installation. However, they come with limitations. Grub screws can damage shaft surfaces if not used with a flat or recessed spot, and they generally provide less holding strength than larger headed fasteners. They can also be difficult to remove if overtightened or if the drive recess becomes stripped. Additionally, effective use requires precise alignment and sufficient thread engagement.

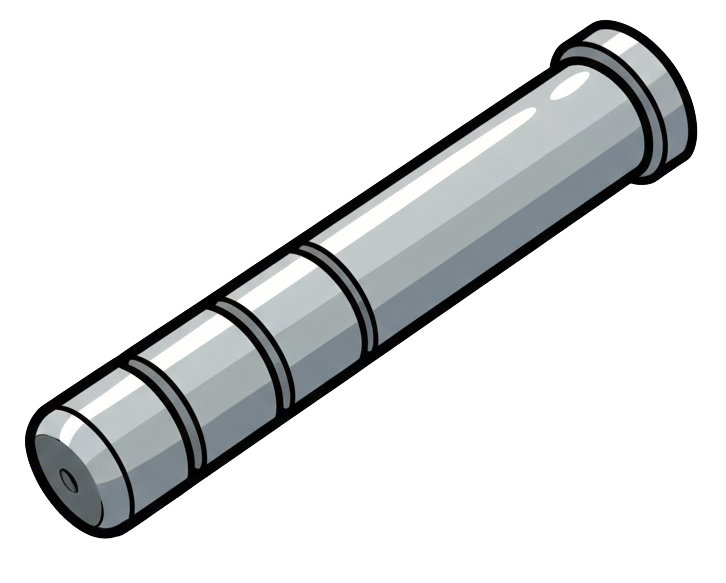

Guide Pin

A guide pin is a precision alignment component used to locate, position, or guide parts so they come together in the correct orientation during assembly, machining, molding, or mechanical movement. In industrial settings—especially manufacturing, tooling, dies, fixtures, robotics, and machinery—guide pins ensure components line up accurately and repeatably without relying solely on fasteners to provide alignment.

Guide pins are typically made from hardened steel, stainless steel, or tool steels and are ground to very tight tolerances. They are often used alongside bushings, where the pin moves inside the bushing to maintain accurate linear or positional alignment with minimal friction. This combination is common in stamping dies, injection molds, precision jigs, automated equipment, and any system where parts must travel along a repeatable path.

In assembly and fastening applications, guide pins are sometimes used as temporary alignment tools, helping workers position heavy plates, flanges, machinery bases, or structural components so bolt holes line up before permanent fasteners are installed. They reduce cross-threading, speed up assembly, and improve accuracy when installing critical bolts, screws, or dowels.

Key uses include:

- Tool and die alignment (die sets, molds, presses)

- Jigs and fixtures for machining or welding

- Mechanical linkage guidance

- Robotics and automation for controlled motion

- Heavy-equipment or structural assembly to align bolt holes before installation

Gusset Plate

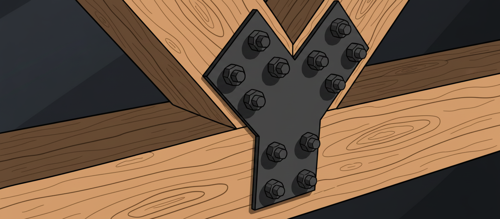

A gusset (or gusset plate) is a reinforcing plate or bracket used to add strength, stability, and rigidity to a mechanical or structural joint. Think of it as an additional piece of material—often steel—placed at the intersection of two or more components to prevent deformation, distribute loads, and keep the connection from flexing or failing.

Gussets are extremely common in steel fabrication, structural engineering, machinery, heavy equipment, and industrial frameworks. They are typically welded, bolted, or riveted into place and serve to spread out stress across a wider area so that no single bolt or weld line carries the entire load. In structures like bridges, towers, frames, conveyors, trailers, racking, and equipment housings, gussets keep the geometry square and stable under compression, tension, shear, and dynamic loading.

From a fastener perspective, gussets often rely heavily on bolted connections—frequently using high-strength fasteners (Grade 5, Grade 8, ASTM A325/A490, or metric 8.8/10.9)—because the gusset plate must transfer significant forces between the members it connects. The gusset plate’s size, thickness, hole pattern, and fastener grade are all engineered to match the load requirements of the system.

AKA: Gusset Plate