Resources

Glossary

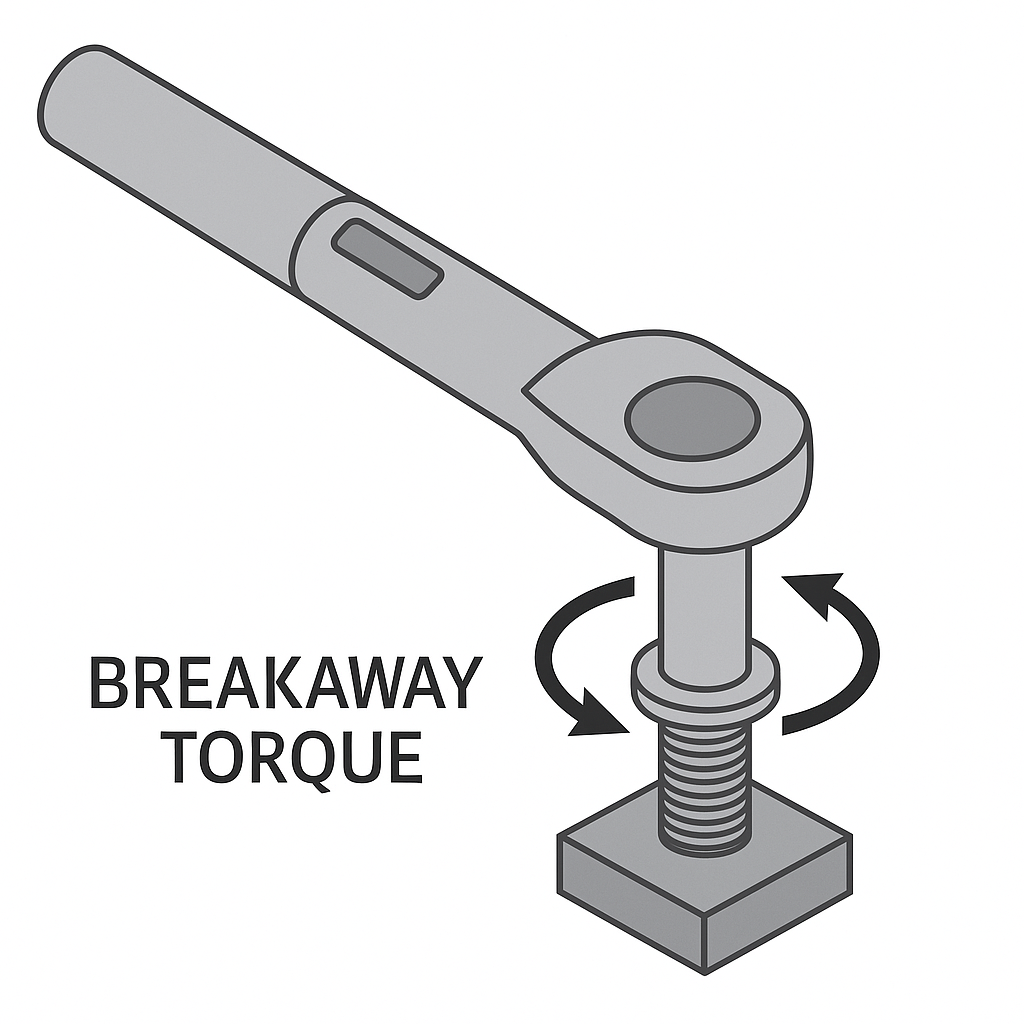

Breakaway Torque

Breakaway torque is the amount of torque needed to start turning a fastener after it has been tightened and is at rest. It measures the force required to overcome static friction between the threads or surfaces.

This value is important for testing locking fasteners, coatings, and lubricants, as well as for quality control in industries like aerospace and automotive. It ensures that fasteners resist loosening and remain secure under vibration or load.

Digital Torque Wrench

A digital torque wrench is a precision tool used to measure and apply a specific amount of torque to a fastener—such as a bolt or nut—while providing real-time electronic feedback. Unlike traditional click or beam-type torque wrenches, a digital torque wrench uses electronic sensors (typically strain gauges) to detect the applied torque and display it on an LCD or LED screen, often in multiple units (Nm, ft-lb, in-lb).

These tools ensure that fasteners are tightened to the exact specification required—critical in industries like automotive, aerospace, energy, and precision manufacturing, where incorrect torque can lead to equipment failure or safety risks.

Many digital torque wrenches feature audible, visual, or vibrational alerts that notify the user when the target torque value is reached, improving accuracy and repeatability. Advanced models also include data logging, wireless connectivity (Bluetooth or USB), and programmable torque settings, allowing for digital recordkeeping and quality assurance in production environments.

Prevailing Torque

Prevailing torque is the measurable turning resistance created by a locking feature in a threaded fastener assembly—the torque required to keep a nut advancing on a bolt (or a screw advancing in a tapped hole) when the bearing surfaces are not yet in contact and no meaningful clamp load is being developed. It exists because the threads are intentionally made to interfere or increase friction, so the assembly “wants” to resist rotation even before the joint is tightened.

Prevailing torque is produced by locking designs such as nylon-insert locknuts, all-metal locknuts with a distorted/elliptical top or other deformed thread section, thread-forming or thread-deforming features, and pre-applied locking patches (nylon/chemical) on bolts or screws. Because it is fundamentally a friction/interference effect, prevailing torque is separate from the torque required to generate preload in the joint. During tightening, the torque you apply is essentially the sum of (1) the torque needed to overcome this locking resistance and (2) the torque needed to overcome underhead/bearing friction and thread friction while stretching the fastener to create clamp load.

Prevailing torque is commonly verified with a run-on/run-off test: the nut is driven onto a bolt (or the screw into a test nut) and torque is recorded while the assembly is free-running with no bearing contact, ensuring the measurement reflects only the locking feature rather than the friction under the nut face or screw head. Standards typically require prevailing torque to fall within a specified range so the fastener provides reliable resistance to loosening, but not so high that it causes galling, thread damage, or impractical installation. Prevailing torque can change with reuse, temperature, lubrication/coatings, plating thickness, and thread condition; nylon inserts and patches may soften at elevated temperatures, while all-metal prevailing-torque nuts may maintain locking performance better in heat but can be more sensitive to galling on stainless or poorly lubricated assemblies.

Prevailing Torque Nut

A prevailing torque nut is a locknut with a built-in feature that creates friction on the threads, producing a constant “drag” (the prevailing torque) as it turns. That friction resists loosening from vibration or shock, even when clamp load is low, making the joint more reliable than with a standard nut alone.

There are two main styles: nylon-insert (Nylock), which uses a polymer ring to grip the bolt and is best for general use but limited to about 120 °C/250 °F and a few reuses; and all-metal (distorted-thread/top-lock), which relies on deformed metal threads to pinch the bolt, tolerating higher temperatures and harsher service with limited reusability (the locking torque drops with cycles). Installation torque specs typically account for the added drag, and performance can vary with plating, lubrication, temperature, and reuse. These nuts are common in automotive, machinery, and structural applications where vibration resistance is critical.

Torque

Torque for fasteners is the rotational force applied to tighten a bolt, screw, or nut so that it generates the proper amount of clamping force between the joined parts. It is one of the most important concepts in fastening because if too little torque is applied, the joint may loosen and vibrate apart, but if too much torque is applied, the fastener can be overstressed, the threads may strip, the joint material may be crushed, or the fastener may even break.

Torque is defined as the measure of a turning or twisting force applied around an axis. In the context of fasteners, it is measured in units such as Newton-meters (N·m), inch-pounds (in-lb), or foot-pounds (ft-lb). Specialized tools like torque wrenches, torque screwdrivers, and automated assembly machines are used to apply and verify the correct torque so that fasteners are tightened properly and consistently.

The main purpose of applying torque is to achieve the proper preload, which is the clamping force created when a fastener is tightened. Preload keeps the joined parts in firm contact, helps resist separation under service loads, and evenly distributes stresses throughout the joint. Correct torque application prevents fasteners from loosening under vibration, protects against separation of the joint, avoids overstressing and yielding of the fastener, and ensures that gaskets or seals are evenly compressed where sealing is necessary.

Several factors affect the amount of torque required for a fastener. Thread size and pitch play a role, since larger and coarser threads generally need higher torque. The material and grade of the fastener also matter, as stronger alloys are designed to handle greater torque levels. Lubrication can significantly reduce friction, meaning less torque is needed to achieve the same preload compared to dry threads. Surface finishes or coatings such as zinc or phosphate also change frictional characteristics, while the type of joint material influences how much torque can be applied before deformation occurs, especially in softer materials.

Torque-controlled fasteners are used in many fields. In automotive and aerospace applications, precise torque is essential for components like cylinder heads, wheel lugs, and aircraft structures. In industrial machinery, torque ensures that bolts in rotating equipment remain tight despite vibration. In construction, torque is used to secure structural fasteners in frameworks or bridges. In electronics and precision assemblies, small screws require very specific torque levels to prevent stripping.

Applying the correct torque provides key advantages. It ensures safety and reliability in assemblies, increases the lifespan of fasteners by preventing overstressing, and maintains the performance of gaskets, seals, and structural joints. However, torque does have limitations. It does not directly measure clamping force, but instead serves as an indirect method since much of the applied torque is lost to friction. Variations in lubrication, thread condition, or surface material can cause significant differences in preload even when the same torque is applied. For highly critical applications, more precise methods such as torque-angle tightening or the use of tension control bolts are employed to improve accuracy and consistency.

Torque Resistance

Torque resistance is a measure of a component or fastener’s ability to resist rotational movement when a twisting or turning force (torque) is applied. In simple terms, it describes how well a part can stay locked in place and prevent spinning within its mounting material when subjected to torque during assembly or service.

In the context of mechanical fasteners—especially self-clinching nuts, studs, threaded inserts, and press-fit components—torque resistance ensures that the fastener does not rotate when a mating screw or bolt is tightened or loosened. For instance, when you tighten a screw into a self-clinching nut embedded in sheet metal, the nut must remain stationary to allow proper tightening. Its torque resistance is what prevents it from spinning freely inside the sheet.

The resistance to rotation usually comes from mechanical interlocking or surface friction between the fastener and the surrounding material. In self-clinching fasteners, this is achieved by knurls, serrations, ribs, or undercut grooves on the fastener’s body that grip the surrounding metal when pressed in under high pressure. The sheet metal cold-flows into these features during installation, creating a permanent interlock. This interlock provides both axial retention (resisting pull-out) and torque resistance (resisting spin).

Torque resistance is often tested by applying a rotational load to the fastener until it begins to slip or rotate within its host material. The measured value (typically expressed in inch-pounds or Newton-meters) represents the fastener’s torque-out strength. This property is especially important in applications subject to vibration, dynamic loads, or frequent assembly/disassembly, such as in automotive panels, aerospace structures, and electronic housings.

Torque resistance differs from axial retention, though both work together to keep a fastener secure. Axial retention prevents the fastener from being pulled straight out, while torque resistance prevents it from twisting or turning out of position.

Torque Sensor

A torque sensor is a device that measures the rotational force (torque) applied to a shaft, bolt, motor, or mechanical system. Torque is a measure of how much a force causes something to rotate and is typically expressed in Newton-meters (N·m), pound-feet (ft-lb), or inch-pounds (in-lb). Torque sensors convert that mechanical twisting force into an electrical signal that can be read by instruments, test equipment, or control systems.

Torque sensors work by detecting strain caused by twisting. Inside the sensor, a shaft or flexing element slightly deforms when torque is applied. That deformation is measured using one of several technologies:

- Strain gauge sensors use bonded strain gauges in a Wheatstone bridge to detect microscopic stretching under load.

- Magnetoelastic sensors detect changes in magnetic permeability as a shaft twists.

- Optical and capacitive sensors measure displacement or angle between components.

- Reaction torque sensors measure force without requiring rotation, often mounted in static fixtures.

- Rotary torque sensors measure torque on spinning shafts using wireless telemetry or slip rings.

Torque sensors are critical in engine testing, electric motors, robotics, fastener testing, wind turbine drives, industrial automation, and quality control for bolted joints. For example, when tightening fasteners, a torque sensor can verify applied torque to ensure joints are neither under-tightened (risking loosening) nor over-tightened (risking bolt yield or fracture).

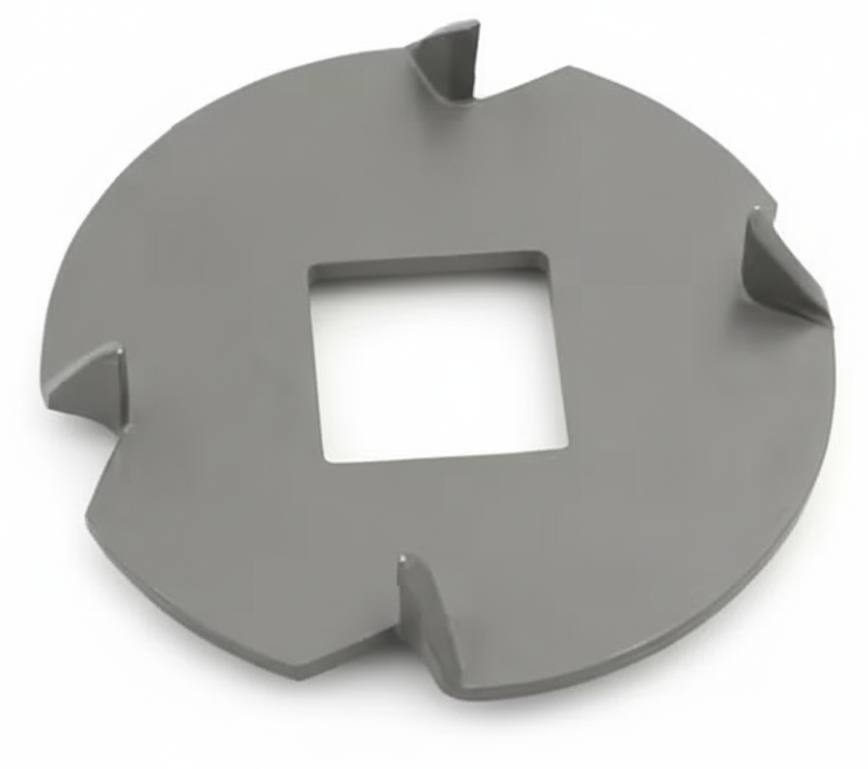

Torque Washer

A torque washer is a washer specifically designed with locking or anti-rotation features that help prevent nuts, bolts, or screws from loosening under torque, vibration, or heavy load. Unlike a standard flat washer, which serves only to spread load, a torque washer actively resists movement of the fastener once tightened, making it an important component in assemblies where reliability is critical.

Torque washers are generally manufactured from hardened steel, stainless steel, or other strong alloys to endure repeated tightening and heavy stresses. Their distinguishing characteristic is the geometry of the inner or outer surface, which interacts with the fastener or the clamped material to resist rotation. Designs vary widely. Some have serrated or toothed faces that grip against the fastener head or the surface of the joint. Others feature square or rectangular holes designed to fit over carriage bolt shoulders to prevent turning. Certain types include external protrusions or tangs that bite into the base material or slot into pre-made grooves for added stability. There are also specialized patterns tailored for unique fastener types and applications.

The primary function of a torque washer is to maintain consistent clamping force in joints subject to torque and vibration. By resisting rotation of the fastener head or nut, the washer ensures that preload—the clamping force generated during tightening—is not lost. This consistent preload extends joint life, prevents fastener loosening, and enhances safety, particularly in high-stress or dynamic environments.

Torque washers see wide use in many industries. In automotive and aerospace applications, they are used in assemblies exposed to continuous vibration and cyclic loading. In construction, they are commonly found in structural steel joints, heavy machinery, and other bolted connections. In electrical and mechanical systems, they help secure equipment subject to fluctuating forces. Torque washers are also frequently paired with carriage bolts, where their square-hole design keeps the bolt from spinning during tightening in wood or metal framing.

These washers offer several advantages. They effectively prevent loosening under torque and vibration, preserve joint integrity and safety, reduce the need for adhesives or secondary locking methods, and are often reusable depending on material and design. However, they also come with limitations. Torque washers tend to be more expensive than standard flat washers, and their biting edges can damage softer materials. In addition, they may not be suitable for applications where appearance is important, since serrated or toothed surfaces can leave visible marks on the joint material.

Torque-Angle Tightening

Torque-angle tightening is a fastening method that uses a two-step process to achieve a precise and consistent clamping force. First, a specified torque is applied to seat the fastener and eliminate any clearance. Then, the fastener is rotated further by a defined angle of rotation. This process produces a more accurate preload compared to torque-only tightening, because it minimizes the effect of friction between the threads and under the bolt head.

In practice, torque-angle tightening begins with a torque wrench or specialized tool applying a snug torque, which ensures the fastener is properly seated. Once this initial torque is reached, the fastener is rotated an additional specified angle, such as 90°, 120°, or 180°. The measured angle corresponds to a predictable elongation of the fastener, and this elongation directly generates bolt tension, which in turn creates the clamping force required for the joint.

The main purpose of torque-angle tightening is to achieve consistent preload in bolted joints. Friction under the head and in the threads can account for 80–90% of applied torque, meaning torque alone often results in significant variation in clamping force. By focusing on the fastener’s elongation instead, torque-angle tightening controls the actual stretch of the bolt rather than relying solely on torque readings, providing more reliable and uniform results.

This method is widely used in critical applications. In automotive engines, it is common for cylinder head bolts, main bearing caps, and connecting rod bolts. Aerospace and heavy machinery industries also rely on torque-angle tightening to ensure that joints subjected to heavy loads and vibration maintain consistent preload. It is also applied in structural and high-load assemblies where precise and repeatable bolt tension is essential.

The advantages of torque-angle tightening include its ability to deliver highly consistent preload regardless of friction variations, a reduced risk of both under-tightening and over-tightening, and improved joint reliability in demanding applications. It is especially effective with torque-to-yield (TTY) bolts, which are designed to be tightened beyond their elastic limit to achieve maximum clamping force.

However, the method does have limitations. It requires specialized equipment to accurately measure the angle of rotation, making it more time-consuming than simple torque tightening. Torque-to-yield bolts used with this method are also single-use fasteners and must be replaced once removed. Additionally, torque-angle tightening is not always necessary for non-critical or low-load assemblies, where simpler torque methods may be sufficient.

Torque-to-Yield Bolt (TTY)

A Torque-to-Yield (TTY) bolt is a fastener designed to be tightened beyond its elastic limit into the plastic range, meaning it permanently stretches slightly during installation. Instead of relying on torque alone, these bolts are tightened in two steps: first to a specified torque value, then by a set angle of rotation. This method ensures a highly accurate and uniform clamping force, making TTY bolts especially useful in critical applications such as engine cylinder heads, main bearings, and connecting rods, where consistent pressure is vital to prevent leaks or failures.

Because they are stretched past their yield point, TTY bolts cannot be safely reused—once removed, they must be replaced. While more costly and requiring precise torque-angle tools, their ability to deliver consistent load distribution makes them a preferred choice in demanding environments where reliability is essential.

AKA: Stretch Bolt