Resources

Glossary

Hall-Héroult Process

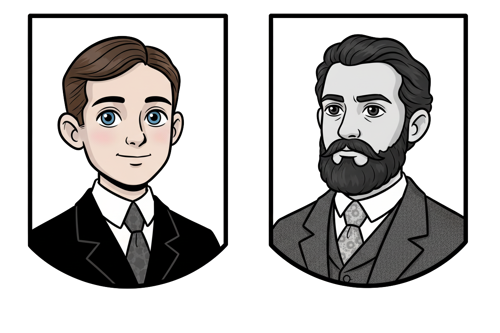

The Hall–Héroult process is the main industrial method for producing pure aluminum metal from alumina (aluminum oxide, Al₂O₃), which is first refined from bauxite using the Bayer process. Developed independently in 1886 by Charles Martin Hall in the United States and Paul Héroult in France, this process transformed aluminum from a rare, costly laboratory curiosity into a mass-produced, everyday material.

At its core, the Hall–Héroult process is an electrolytic reduction system that uses electric current to separate aluminum from oxygen in molten alumina. Because alumina has a very high melting point of about 2,050°C, it is dissolved in molten cryolite (Na₃AlF₆), which lowers the operating temperature to roughly 950–1,000°C. The electrolytic cell—known as a reduction pot—is a carbon-lined steel container that serves as the cathode, while large carbon blocks suspended from above act as the anodes. Additives like aluminum fluoride (AlF₃) and calcium fluoride (CaF₂) are often used to enhance electrical conductivity and stability.

When alumina is introduced into the molten cryolite bath, it dissolves and separates into aluminum ions (Al³⁺) and oxide ions (O²⁻). As a powerful direct current passes through the cell, these ions migrate to their respective electrodes. At the cathode, aluminum ions gain electrons and are reduced to molten aluminum metal through the reaction Al³⁺ + 3e⁻ → Al (liquid). At the same time, at the carbon anode, the oxide ions lose electrons and react with carbon to form carbon dioxide gas, following the oxidation reaction C + O²⁻ → CO₂↑ + 4e⁻. These two reactions occur simultaneously, continuously producing aluminum while consuming the carbon anodes in the process.

The newly formed molten aluminum collects at the bottom of the cell because it is denser than the electrolyte, and it is periodically siphoned off and cast into ingots, billets, or other industrial forms. The carbon anodes gradually burn away as they react with oxygen to form CO₂, so they must be regularly replaced. Modern smelters typically use either prebaked carbon anodes or self-baking anodes, depending on the design of the reduction cells.

The Hall–Héroult process is extremely energy-intensive, requiring roughly 13–15 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity per kilogram of aluminum produced, which is why aluminum smelters are often built near hydroelectric or geothermal power sources. The process operates continuously under carefully controlled voltage, temperature, and composition to maintain purity and efficiency.